William Grimshaw, Veteran of the American War for Independence

William Grimshaw fought in the American Revolutionary War on the side of the Colonials. He was a member of Hazens Regiment, which was initiated in Canada by Moses Hazen near the beginning of the conflict. Apparently Williams service began in January 1782 and continued until the regiment was disbanded* in June 1783, a period of about 18 months. Records indicate that William was a fifer and that he served in Captain (Clement or Louis) Gosselins Company. He caused a casualty in February 1782 – a man named Musick or Musiak. After the war he received bounty land for his service, receiving Bounty Land Warrant No. 13129, dated March 25, 1790.

The records and related information on William’s Revolutionary War service are presented on this webpage. After the war, William settled in New Hampshire for nearly 25 years (1788 to 1812) and then probably moved on to Vermont, New York and Canada. Information on William’s life after the Revolutionary War is is provided on a companion webpage, and the associated records are on another companionwebpage. Census records for New Hampshire indicate that was living in Grafton County in 1790, 1800 and 1810. His date of death and place of burial have not yet been determined, but he probably died in Upper Canada after migrating there from New Hampshire.

*

Although formal disbandment did not occur until November, most soldiers (including William) were furloughed in June.

Contents

Origins and Descendants of William Grimshaw

Was William Grimshaw the Son of John and Hannah (Fieldhouse) Grimshaw?

Engagements of Hazens Regiment

Revolutionary War Service Records of William Grimshaw

Bath, NH Military Service Monument

Post-War Difficulties of Moses Hazen and Members of His Regiment

Bounty Land Area for Hazens Regiment

John Grimshaw, Another Revolutionary War Veteran

Close-up Images of Williams Revolutionary War Records

Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the Revolutionary War

Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783

Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application File

Webpage Credits

Thanks go to Barbara Bonner, Terry Micks, Bill OHalloran and Calvin Lamb for contributing to the knowledge base that makes this webpage possible. Particular thanks to Bill for providing the Bounty Land Warrant and the photos of the monument in Bath, NH shown below.

Origins and Descendants of William Grimshaw

William is undoubtedly descended from a family of Grimshaws with roots in Lancashire, England, but nothing is known of his ancestors or whether he was born in North America or in England. He is believed to be the father of the heads of at least two major Grimshaw families in North America – Zephaniah (who had several families) and George Grimshaw (m. Charlotte Menard) – but this has not yet been proven definitively.

Was William Grimshaw the Son of John and Hannah (Fieldhouse) Grimshaw?

A number of public family trees on Ancestry.com (more than 20 as of February 2013) indicate that William Grimshaw was the son of John and Hannah Grimshaw, which would mean that he is descended from the Edward and Dorothy (Raner) Grimshaw family line in Yorkshire, as shown on a companion webpage. The ancestry chart for William in this case would be as follows:

Edward Grimshaw (About 1559 – 22 Jun 1635) & Dorotye Raner

|–Abraham Grimshaw (1603 – 1670) & Sarah ( – 21 Sep 1695)

|–|–JeremyJeremiah Grimshaw* (21 Jul 1653 – 12 Aug 1721) & Mary Stockton ( – 6 Jan 1692/1693)

|–|–|–Joshua Grimshaw (12 Apr 1687 – 8 Jan 1764) & Jane Oddy (1686 – 1771)

|–|–|–|–John Grimshaw (5 Dec 1723 – ) & Hannah Fieldhouse

|–|–|–|–|–John Grimshaw (20 Jan 1760 – )

|–|–|–|–|–Mary Grimshaw (27 Sep 1761 – 5 Jul 1784)

|–|–|–|–|–William Grimshaw* (1764 – 5 Sep 1829) & Ann Grainger (1768 – 1805)

|–|–|–|–|–|–Jonathan Grimshaw (20 Jul 1784 – ) & Sarah Pickersgill

|–|–|–|–|–|–Hannah Grimshaw (8 Apr 1786 – ) & Joseph Marshall

|–|–|–|–|–|–John Grimshaw (1789 – )

|–|–|–|–|–|–Samuel Grimshaw (1796 – )

|–|–|–|–|–|–Abraham Grimshaw (2 Nov 1797 – 1 May 1874) & Mercy Halliday (4 Jun 1809 – 15 Dec 1877)

|–|–|–|–|–|–Ruth Grimshaw (1799 – )

|–|–|–|–|–|–Ruth Grimshaw (3 Mar 1802 – ) & Joseph Clapham

|–|–|–|–|–|–Benjamin Grimshaw (30 Oct 1803 – ) & Nanny Roundhill

|–|–|–|–|–|–Mary Grimshaw (18 Jun 1805 – )

|–|–|–|–|–|–Ann Grimshaw (12 Sep 1809 – )

|–|–|–|–|–William Grimshaw* (1764 – 5 Sep 1829) & Sarah

|–|–|–|–|–|–Moses Grimshaw (12 Mar 1807 – 1868)

|–|–|–|–|–|–Mary Grimshaw

|–|–|–|–|–|–Ann Grimshaw

However, this identification of William as the son of John and Hannah Grimshaw is apparently in error. William the son of John and Hannah Grimshaw had two spouses, Ann Grainger and Sarah ? and apparently did not leave Yorkshire. Other errors for the identification of William as the son of John and Hannah also seem apparent, such as place of birth (Gorton, which is in Lancashire, not Yorkshire) and date of entry (1820, which is many years too late).

Overview of Hazens Regiment

The earliest known records of William are of his service in Hazens Regiment. Englands defeat of France in the French and Indian War, which ended in 1763, resulted in the cession of Canada to England, A large part of the French Canadian population remained disaffected with England, and when hostilities began that led to the American Revolution, many of them (particularly near the border) sympathized with the Colonials. Many migrated to the U.S. (an under-recognized counter movement to that of the Loyalists who left the American colonies for Canada), and they provided a source of troops for the American side in the Revolution. It was from this population that Moses Hazen successfully raised his regiment, which fought through the entire course of the war.

An excellent description of Moses Hazen and his 2nd Canadian Regiment is provided in a book by Allan S. Everest1. Excerpts from the Foreword, Preface, and Appendix are given below. Additional information on Hazens Regiment is given further down on this webpage.

Foreword

(by John H. G. Pell, Chairman, New York State American Revolution Bicentennial Commission)

When thirteen of Great Britain’s mainland colonies declared for independence in 1776, the newest British colony in North America – Canada – decided against joining the revolt. But some Canadians refused to accept the decision of the majority in Canada to stay out of the fight for American independence. A large group of these people left their homes and crossed the border to be organized into military units by Moses Hazen. Led by Hazen, who was commissioned a general in the Continental army, these Canadian soldiers fought in many engagements throughout the war. After independence was achieved, Hazen led his followers to the northern reaches of New York to settle on land grants near the border of the country they had left years before. The story of these Canadians who came south to support the cause of American independence thus belongs both to New York and to the people of the United States at large.

Preface

(By Allan S. Everest, Plattsburgh, New York, Spring 1976)

This book is an attempt to offer belated recognition of those residents of Quebec and Nova Scotia who, for a variety of reasons, became refugees in the United States during the American Revolution. Whether motivated by the expectation of profit and adventure, anticipation of life in a freer society, or the desire to help drive the British out of Canada, hundreds of them chose what they thought was temporary exile from their homeland.

The refugees from Quebec were largely French, but they were joined by a significant number of Americans who had gone north to seek, and often to make, their fortunes after the conquest of 1763 – Moses Hazen, Edward Antill, James Livingston, Udny Hay, Thomas Walker, and others. From Nova Scotia the refugees were drawn from those transplanted New Englanders who migrated during the 1750s and 1760s but who subsequently caught some of the revolutionary fever that infected Boston in the 1770s. Whoever they were and wherever they came from, they left behind them their property and livelihood, their friends and, for many, their religion.

Most of the men joined the American army, while their families led a long, destitute existence, chiefly in the refugee camps of New York State. The great majority hoped that when the British were driven from Canada they could return to their own country, and they were the most enthusiastic and sometimes troublesome advocates of every new project for an invasion northward.

Although many of the refugees drifted back to Quebec or Nova Scotia after the war and picked up the threads of their prewar life, many more chose to remain permanently in exile. Displaced persons usually present a tragic aspect, and those of the American Revolution are no exception. Many sustained battle wounds or suffered physical breakdowns and the collapse of their prewar standards of living as a result of their war and postwar experiences. A notable example is Moses Hazen, an American who had established thriving enterprises in Canada.

The career of Moses Hazen was so intertwined with the lives and fortunes of the refugees that it is impossible to tell their story without including his. And so this book becomes partly a biography of Hazen and his close associates, from which emerges a stormy and fascinating character. These pages also give rise to a renewed admiration for the patience and integrity of George Washington in his dealings with the refugees and their quarrelsome champion, Moses Hazen.

The fact that there were refugees into the United States is usually forgotten because the focus of attention has been upon the American Loyalists who fled the country during and after the Revolution. The American refugees have always received a great deal of attention, traditionally portrayed as traitors to a great cause. Only recently have they begun to receive the sympathetic study they deserve. Instead of being branded as traitors, they are being appreciated for the idealism of their convictions. Canadians are likewise beginning to display more pride than was formerly the case in the lives of their exiles. In numbers the Canadians were much fewer than the American refugees, which is one reason why the Canadians have been generally overlooked. Another is the fact that the peace treaty at the end of the Revolution made no mention of them although it considerately tried to make possible the return of the American refugees to their native country. Forgotten or otherwise, the refugees created a two-way street, and this study deals with the incoming group

Engagements of Hazens Regiment

Everest1 provides a brief summary of the locations and battles of Hazens Regiment through the course of the Revolutionary War in the Appendix (1976, p. 175-176):

APPENDIX

Locations of the Canadian Regiment During the War

This calendar is as accurate as can be determined for the official assignments of the regiment. It needs to be used with caution, however, because rarely was the entire unit together in one place and under Hazen’s immediate command. His companies were constantly being assigned to detached duty under other commanders, so that the career of a given individual might differ markedly from the following chronology. Furthermore, Hazen himself was often absent from his regiment while recruiting, drumming up support for a Canadian campaign, or just pursuing his personal affairs.

1776 Jun.: left Canada for Crown Point

Jul.: to Ticonderoga

Sep.: to Albany

Nov.: to Fishkill, N.Y., for winter quarters 1777

Jun.: to Princeton, N.J.

Aug.: battle for Staten Island

Sep.-Oct.: battles of Brandywine and Germantown

Fall: to Wilmington, Del., for winter quarters 1778

Feb.: to Albany for the abortive Canadian campaign

Apr.: to West Point

Jul.: to White Plains to help guard New York City

Nov.: to Danbury, Conn., for winter quarters 1779

May: to Coos for roadbuilding

Oct.: to Peekskill, N.Y.

Nov.: to Morristown, N.J., for winter quarters 1780

Summer: to King’s Ferry, N.Y.

Fall: Garrison, N.Y. Campaign to Morrisania

Nov.: Fishkill for winter quarters 1781

Jun.: to Albany and Mohawk Valley to guard against expected British attack

Jul.: to West Point

Aug.: to Dobbs Ferry and northern New Jersey to threaten Staten Island

Sep.: to Williamsburg and Yorktown, Va., for the siege of Yorktown

Dec.: to Lancaster, Pa., to guard prisoners of war 1782

Nov.: to Pompton, N.J., for winter quarters 1783

Jun.: to Newburgh, N.Y. Furloughing begun

William Grimshaw joined the unit in early 1782 and served for 18 months, until its soldiers were furloughed in June 1783, in anticipation of disbandment of the regiment.

Revolutionary War Service Records of William Grimshaw

Records documenting Williams service are to be found on microfilm at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Some of the records are also held in duplicate at the library of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, also located in Washington. Three records of Williams service have been identified in National Archives publications and are shown below. Additional detail, and associated images, are included further down on this webpage.

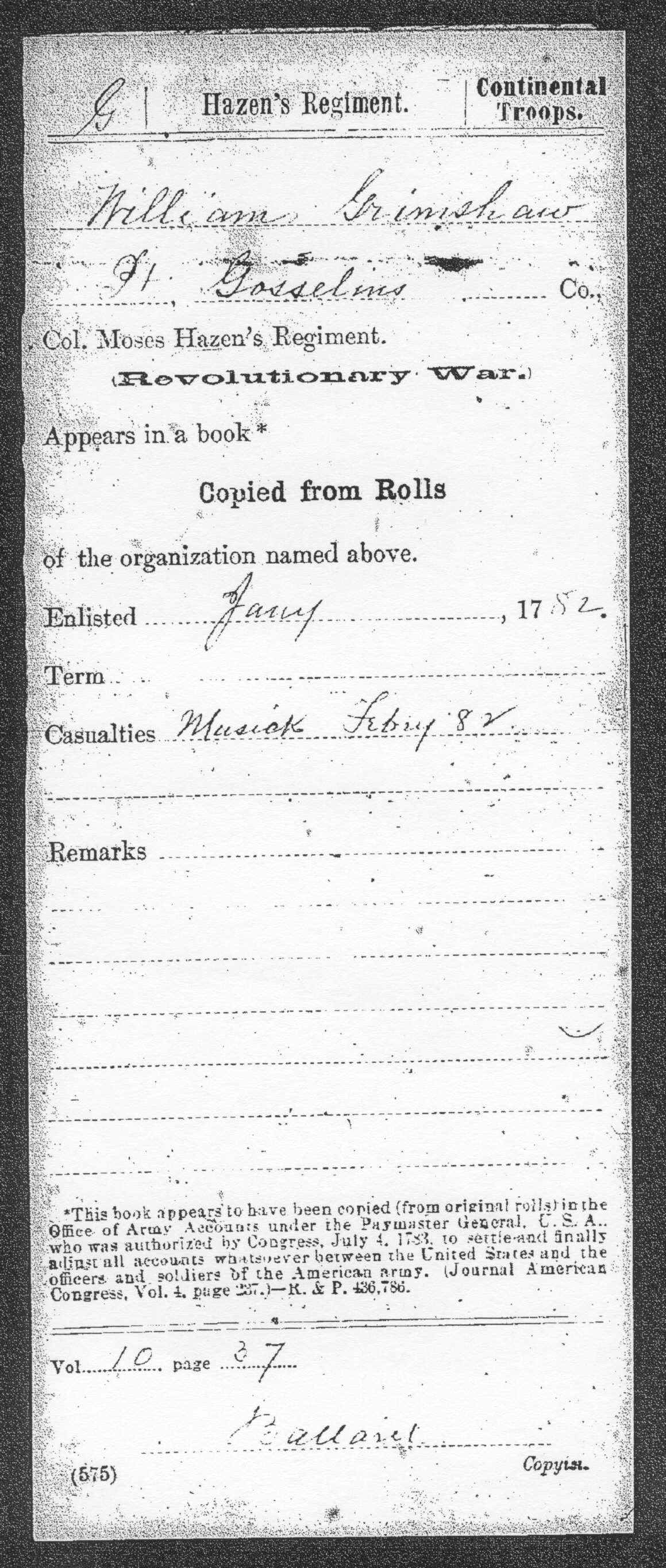

Compiled Service Record (National Archives M8812)

This record (see Figure 1, below) consists of a card, and its jacket, showing Williams assignment to Gosselins company, his enlistment in January, 1782, and his having creating a casualty – Musick or Musiak. The card notes information in a book that was “copied (from original rolls) in the office of Army Accounts under the Paymaster General, U.S.A., who was authorized by Congress, July 4, 1783, to settle and finally adjust all accounts whatever between the United States and the officers of the American army.”

Figure 1. Copy of William Grimshaws record of service in Gosselins Company (of Hazens Regiment) as it appears in the compiled service records of Revolutionary War soldiers. The record is shown on the left, and the jacket containing the record is on the right.

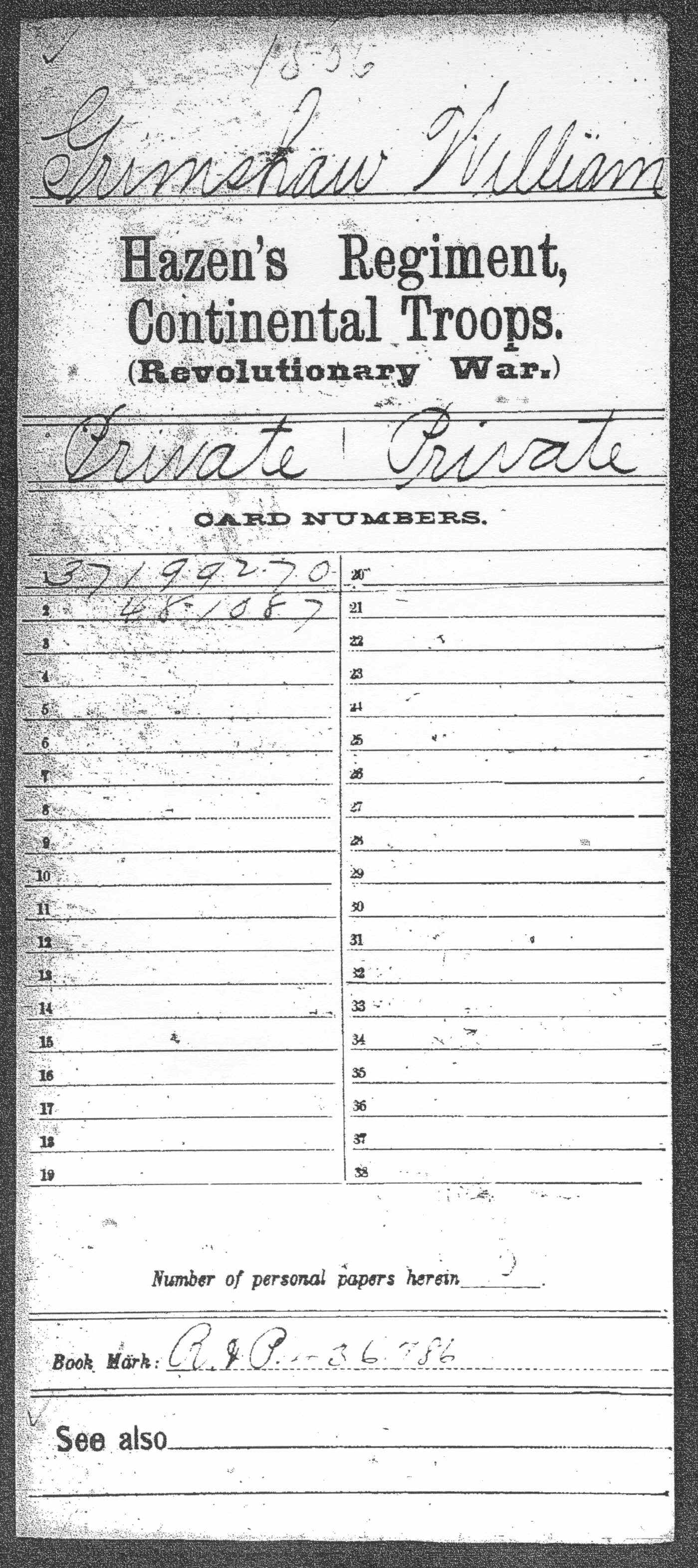

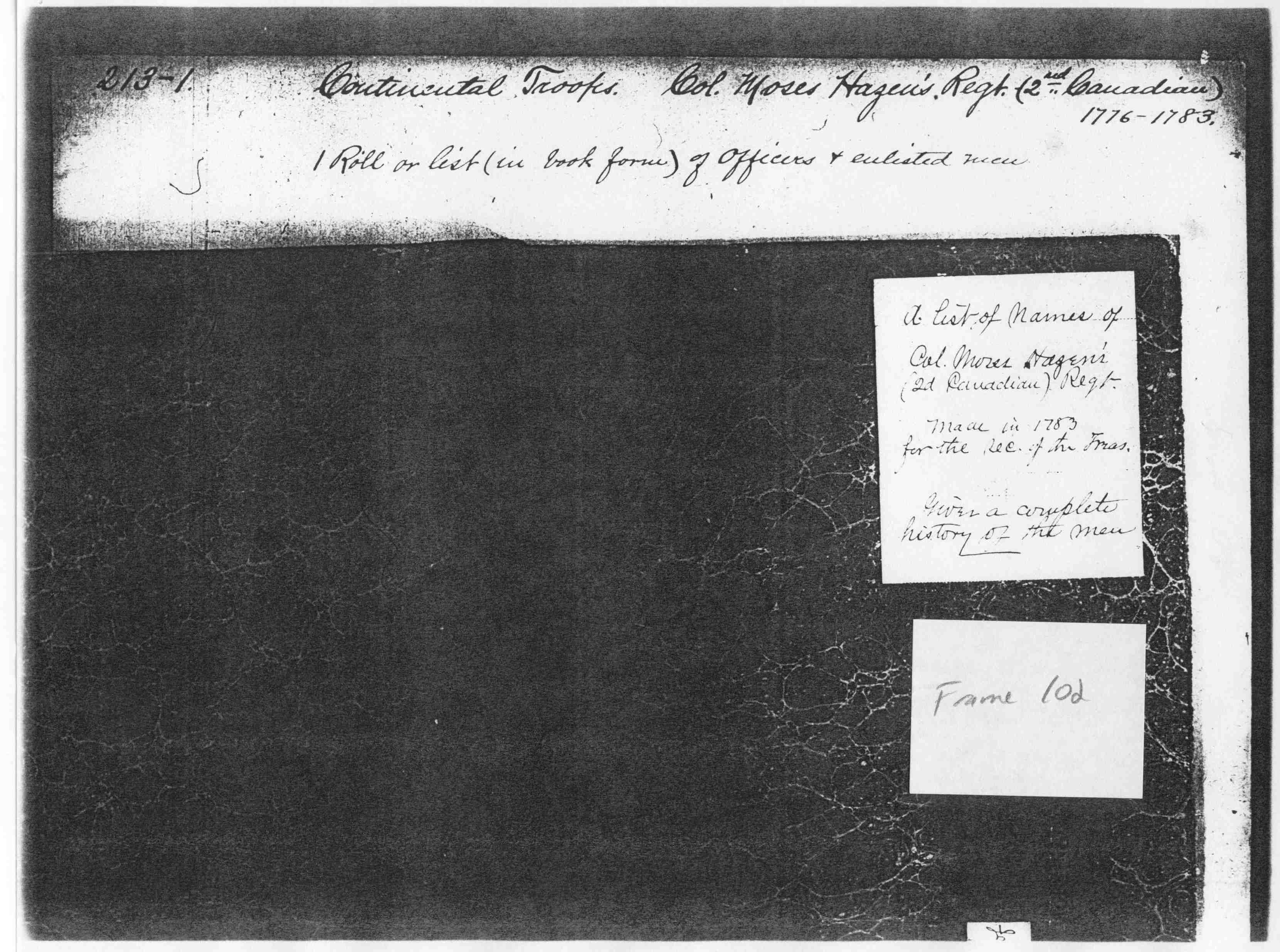

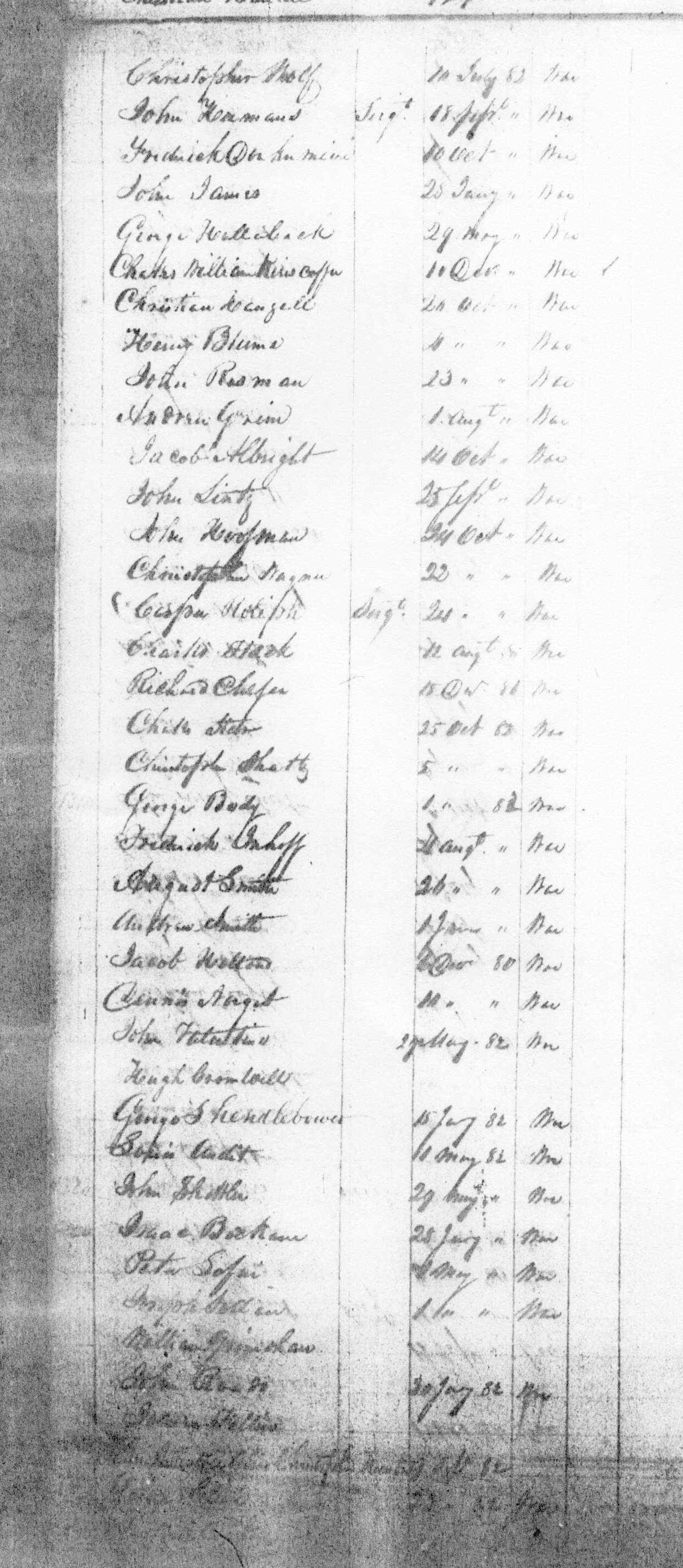

Post-War Regimental Roster (National Archives M2463)

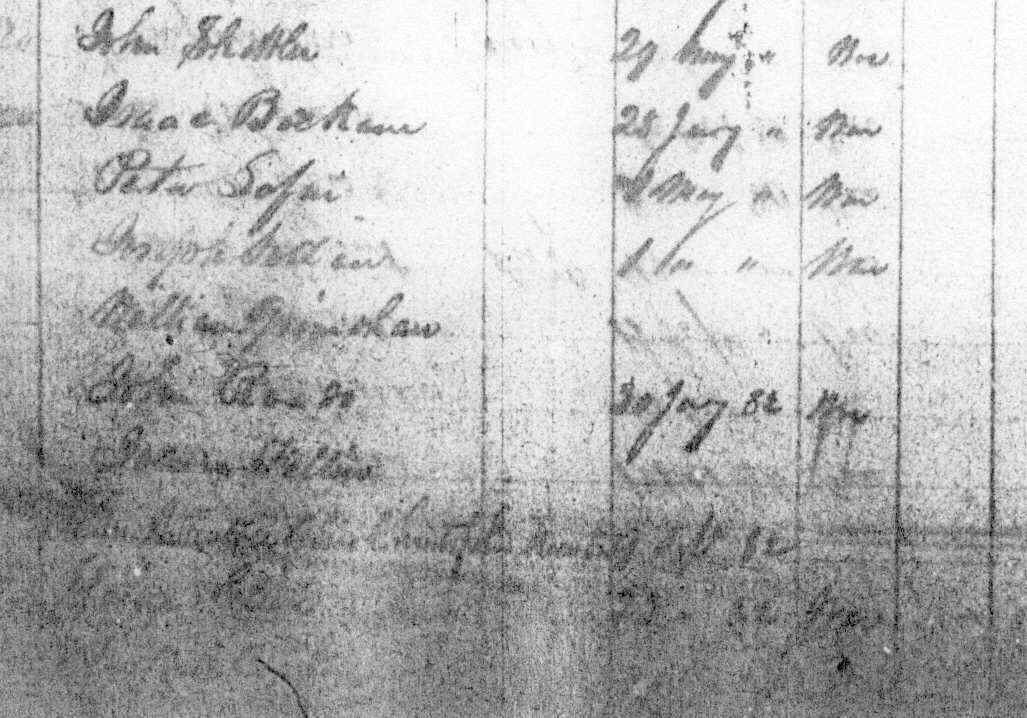

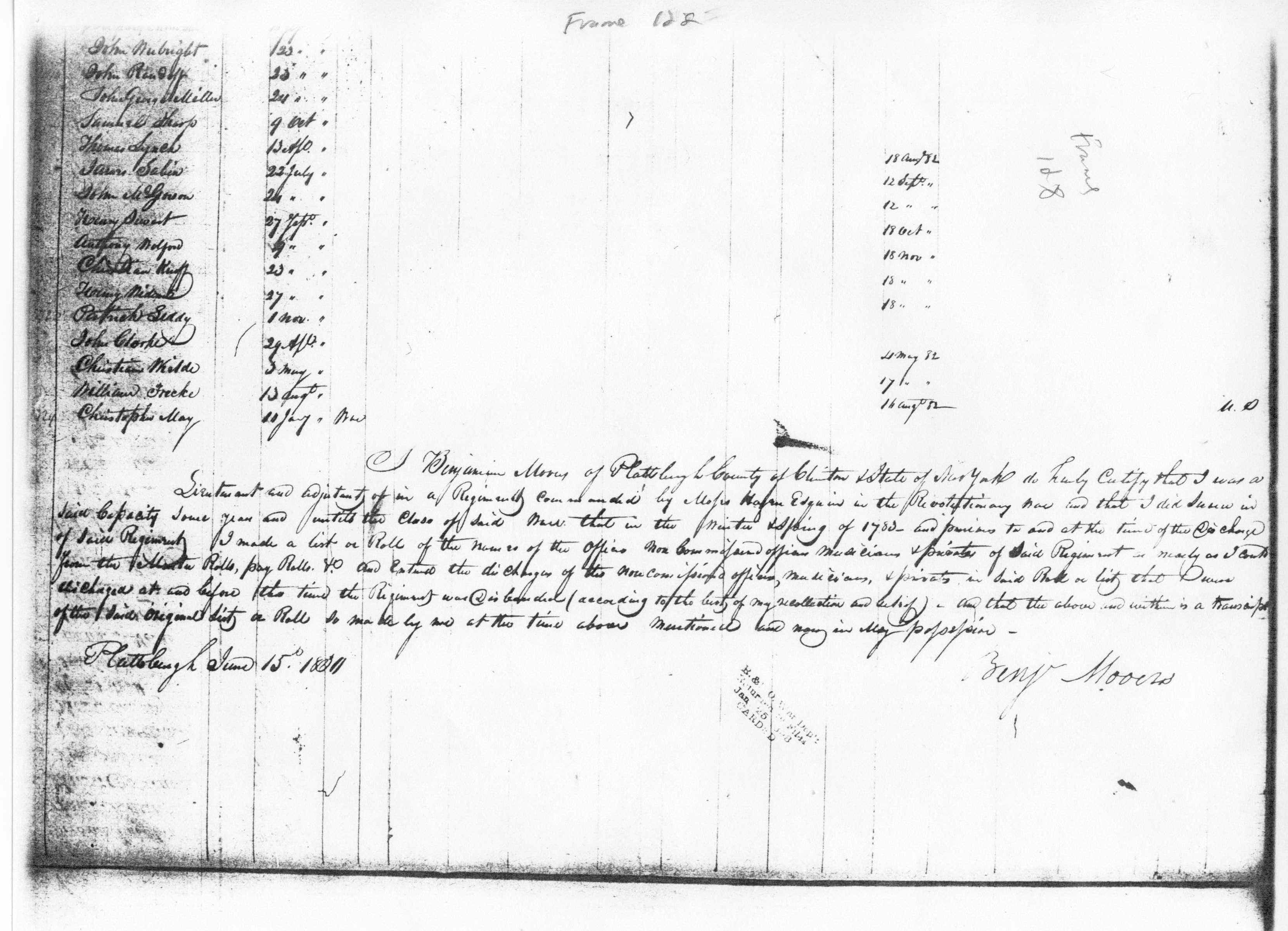

This record consists of a list of members of Hazens Regiment, prepared by Benjamin Mooers and dated June 15th, 1800. William Grimshaws name appears near the bottom of the second to last page (see Figure 2 below) along with the date of termination of his service on June 30, 1783.

Figure 2. Record of William Grimshaw on roster of Hazens Regiment, prepared by Benjamin Mooers, June 15, 1800. The first image is from the front of the record (frame 102 of the microfilm). The second and third images are of Williams name on the list (frame 126). His name appears on the next-to-last page of the list. The fourth image is from the bottom of the list (frame 128) and includes Mooers certification of the list.

Page at front of record:

Page with William Grimshaw entry (upper image shows page with William’s name near the bottom, third from last; lower image is closer view of the name) is shown below. The left half of the page is shown so the name is clearer and because there is only one entry in another column, which shows William’s release from service on June 30, 1783.

Page at end of record:

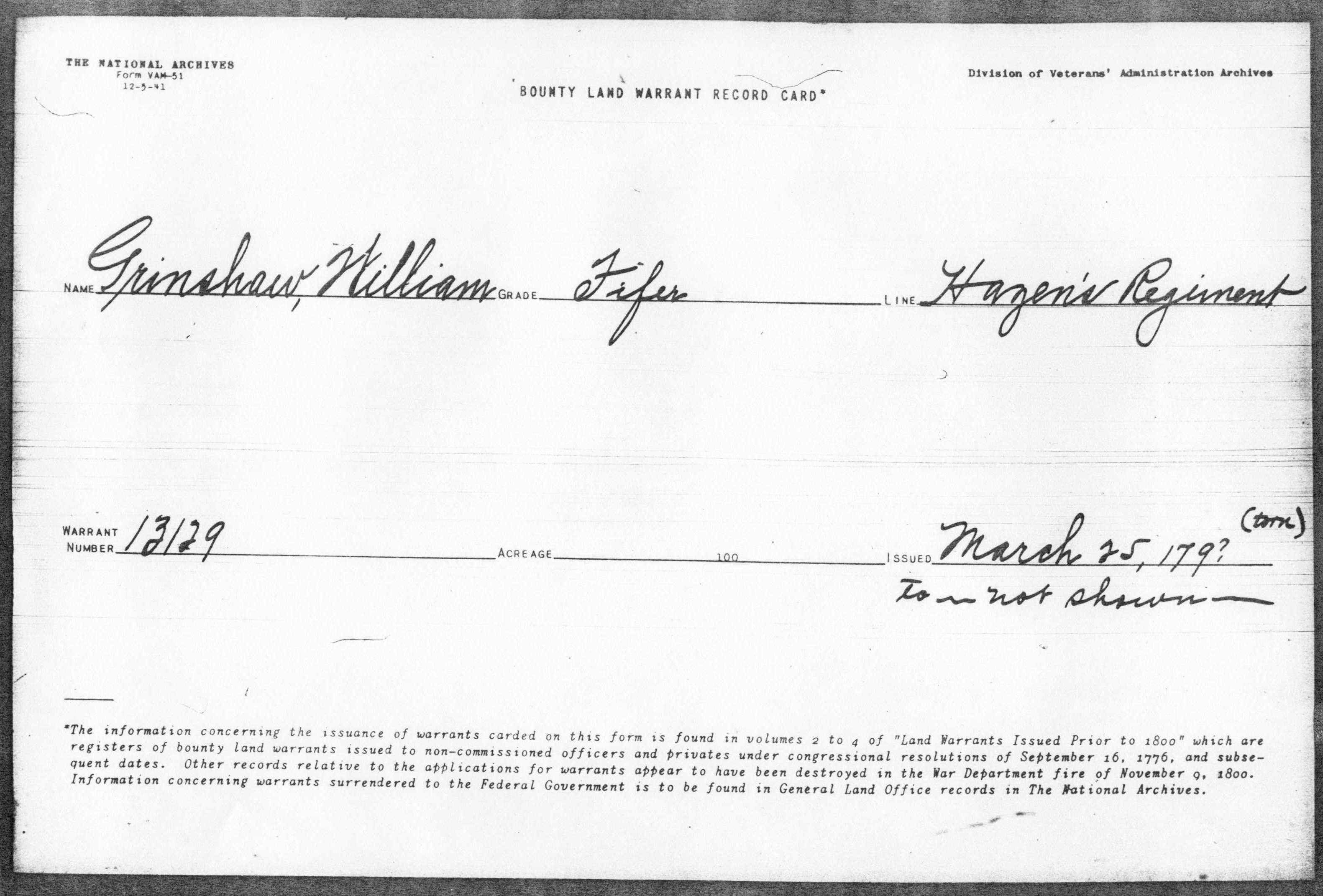

Bounty Land Warrant Records (National Archives M8044 and M8295)

Until 1917 a system of granting bounties to encourage military service was used in the U.S. and was apparently quite prevalent during the Revolutionary War. The bounty system is described as follows in Encyclopedia Britannica Online6:

Bounty System. In U.S. history, program of cash bonuses paid to entice enlistees into the army; the system was much abused, particularly during the Civil War, and was outlawed in the Selective Service Act of 1917. During the French and Indian Wars, the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War, military bounties included land grants as well as cash payments; Civil War bounties were in cash only.

There are two records at the National Archives for William Grimshaw’s Bounty Land Warrant. The first is a copy of a card indicating the warrant, Number 13129 (see Figure 3 below.) The original document was reported lost in a fire on November 9, 1800. However, Bill O’Halloran found a copy of the record in National Archives M8295 (see Figure 4 below.) (Thanks to Bill for contributing this record, and associated image, to the website.)

Williams warrant is also described in White7 as follows:

GRINSHAW [sic], William, BLW #1312-100-25 Mar 179?

Figure 3. Bounty Land Record Card including William Grinshaw (sic) warrant number 13129. The year of issuance is indicated as indeterminable from the original record because of a tear in the document.

Figure 4. Copy of Bounty Land Record for William Grimshaw (warrant number 13129.) Note that date of issuance is March 25, 1790, notwithstanding indication on the record card (Figure 3, above) that the date was not determinable because of a tear in the document.

The following thumbnail (click on it) shows the Bounty Land Warrant in full size. This version is similar to the one pictured above, except that the “hole” in the lower center has been filled in. Many thanks to Barbara Bonner for making arrangements to have this restoration done.

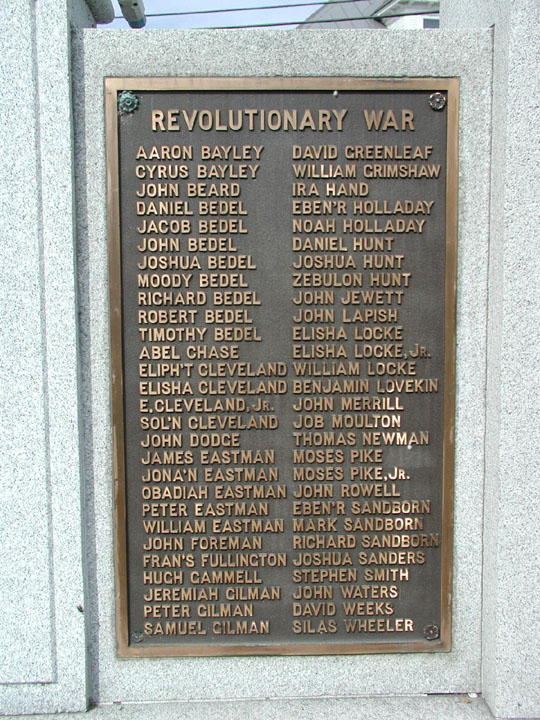

Bath, NH Military Service Monument

The community of Bath, in Grafton County, New Hampshire, erected a monument in 1929 to honor its citizens who had given military service in wars up to that time. William Grimshaws name is included on a plaque for those who served in the Revolutionary War (see Figures 4, 5 and 6 below). Deep appreciation is expressed to Bill OHalloran for providing these photos.

Figure 4 (below). Front view of monument in Bath, NH. Dates 1769 – 1929. The inscription on the main plaque reads, “In honor of the men who enlisted from Bath in the Wars of our country. Erected by the town.”

Figure 5 (below). Rear view of monument in Bath, NH. The plaque for Revolutionary War veterans is on the left side of the monument.

Figure 6 (below). Close-up of plaque showing William Grimshaws service in the Revolutionary War.

New Hampshire Census Records

Following his Revolutionary War service, William apparently settled in Grafton County, New Hampshire and remained there at least through 1810. The records of his presence in that state are presented on a companion webpage. Census records exist for William for the 1790, 1800 and 1810 Censuses. The 1790 Census8 indicates that William and his family were living in Lyman Town and the family included five persons:

1 free white male of 16 years and upward, including heads of families

1 free white male under 16 years

2 free white females, including heads of families

The Census of 18009 indicates that the Grimshaw family was in Coventry Township of Grafton County and included the following seven persons:

3 free white males under 10 (years of age)

1 free white male of 10 and under 16

1 free white male of 26 and under 45, including heads of families

1 free white female of 10 and under 16

1 free white female of 26 and under 45, including heads of families

The index to the 1810 Census10 indicates that William was living in the town Haverhill, Grafton County. According to Bill O’Halloran, who has examined the record, the following seven persons are listed:

1 male of 10 and under 16

1 male of 45 or over

4 females under 10

1 female of 26 and under 45

Post-War Difficulties of Moses Hazen and Members of His Regiment

The contributions of Moses Hazen and the members of his 2nd Canadian Regiment in the Revolutionary War apparently did not result in very substantial rewards and, in many cases, brought personal and financial hardship instead. For example, being assigned directly to Congress (which was chronically impoverished) rather than to one of the states, did not bring enhanced status, recognition or reward, but was a strong disadvantage in most respects. The difficulties experienced by Hazen, members of his Regiment and other Canadian refugees are well summarized in the Afterword of Everests1 book (p. 171-174):

Afterword

The career of Moses Hazen spanned the epic period of two great wars – the struggle with France for control of North America, and the American Revolution. In both he played a creditable and occasionally brilliant role. Most of his service in the French and Indian War was spent as a Ranger which involved the dashing but brutal kind of warfare instigated by the notorious Ranger Commander, Robert Rogers. Indeed, Hazen came to be thought of as Rogers’ counterpart in the Canadian theatre of operations. Despite the stain of the massacre at St. Anne, he was promoted and ultimately taken into the prestigious British Forty-fourth Regiment, from which he was retired on half pay for life. If he had been willing to accept the chances of regimental assignments abroad, he probably could have become a career officer in the British army. But he developed a yearning to become a member of the landed gentry, and he went a long way toward attaining that goal by his feverish search for property in Canada.

The American Revolution completely demolished his way of life. His seigneury lay in the path of the American invasion of 1775. For a man of his temperament neutrality was impossible, but the choice of sides occasioned excruciating pains of indecision. On the one hand his fellow countrymen were the invaders; on the other, he owed his military pension and his Canadian estate to British authority. At first his loyalty was British but then, for reasons he never fully explained but which were probably based on his belief in American victory, he tendered his services to the American cause. Once he had made up his mind, he never wavered in his loyalty even though he knew long before the end of the war that Canada was not going to be conquered.

For his choice he paid a high price. Never again would he be a seigneur on the Richelieu, with all the privileges it entailed. Indeed, before he left Canada he saw his buildings and crops utterly destroyed. He received compensation for only those parts of his estate that were confiscated for the use of the American army, and after the war he failed to regain his Canadian property.

The men and their families that he led out of Canada suffered as much as he, although they had fewer material things to lose. Either deluded by the expectation of personal gain, or inspired by the vision of a liberated Canada, they accepted temporary exile until the day they could return as freedom-bearing conquerors. Although several plans were later projected for an “irruption” into Canada, no campaign actually developed. Consequently, Hazen’s men never had the opportunity to free Canada from British rule or to return home as warriors at all. And the families who followed them as refugees existed on a meagre public dole for more than a decade.

Most of the difficulties that befell Hazen and his Canadians were beyond their power to correct. The regiment was created and staffed as a special unit subject only to an already overburdened Congress, whereas the rest of the army consisted of units based upon individual states. A few of the states were no more alert to the needs of their men than was Congress, but others, such as Massachusetts, were timely and generous with their assistance. Since Massachusetts tended to be used as a model, Hazen’s regiment suffered from a decline in morale whenever comparisons were made. The problem of morale also divided the regiment internally because Hazen, lacking enough Canadians to complete a regiment, was directed to recruit among the states with the result that he led a mixed group, a minority of whom were Canadians. His American officers and men were regularly serviced by their state of origin, but his Canadians had to wait for the dilatory actions of an impoverished Congress. Their sharpest grievance was the congressional system of promotion according to state quotas, which contained no separate quota for the Canadian regiment. Consequently, no Canadian officers received promotions during the seven years many of them served. Only at the end of the war were some of them granted brevet, or honorary, promotions, and those carried no increase in pay or other benefits.

In spite of these drawbacks the regiment gained a reputation for its fighting qualities, although sometimes referred to as the “Infernals.” Three years after the war it was rewarded with a large grant of land in northern New York. But the majority of the Canadians preferred to sell out and take their chances back in Canada, where they tried to reestablish their old relationships with homeland and church, from which they had been separated for so long.

Just as during the two wars, when the mercurial Hazen had reflected the spirit of the times, so in the post-Revolutionary world he imbibed the prevailing feeling of freedom from restraint and the vision of a new country waiting to be exploited. In common with many others of his generation he was a speculator in lands, certificates, and other public securities. His ambitions outran both his judgment and his financial resources; his restlessness drove him into ever more impractical projects, and his indebtedness landed him in jail fourteen times. Yet some of his contemporaries William Duer, Alexander Macomb, and Robert Morris – also spent time in jail after the collapse of even larger speculative enterprises than Hazen seemed to dream of.

Hazen differed from the others in two important respects: he suffered a physical breakdown, and several of his arrests involved money owed him by Congress. He shared with other speculators an insatiable appetite for personal gain. He was, moreover, a victim of circumstance as well as of his own makeup. Through no fault of his own he and his regiment occupied an anomalous position throughout the war; he could not persuade Congress to settle his accounts during his lifetime, and he lacked the influence and resources to battle Christie for control of his Canadian property.

Yet when all this is said in his behalf, he might after the war have lived a life of comfort, dignity, and attention to a few selected projects. But instead of learning to live with his difficulties, he seemed compelled to be doing things, anything, so long as he kept in motion. A psychologist’s reflection on Hazen’s life leads him to the following conclusion:

The picture is that of an individual driven by uncontrollable personal forces, going from one pointless activity to another, one useless acquisition to another, one inconsistent commitment to another, none of these being at any time integrated into a coherent system of living. It is the picture of a person driven, rather than driving, whose seemingly advantageous activities in fact brought with each of them an ominous increase in his already chronically high physical tensions which, producing in their turn premature physiological features of senility, eventually resulted in a stroke, a cerebral catastrophe quite unusual in a man of his age, a final explosion of energy almost typical of the way he lived his life.’

Moses Hazen was a man obsessed. Knox saw him marked by “as obstinate a temper as ever afflicted humanity.” His agent, William Torrey, found him impossible to work for: he could not stand disagreement; he got so angry “I expected he would go into fits,” and “courts & law suits seem to occupy much of his thoughts.”

These comments were made after his stroke. Yet throughout his life he was restless, impatient of restraints and deeply frustrated when he could not brush them aside, aggressive, combative, and stubborn. He was hypersensitive on the point of his own honor and took personally any criticisms of his command’s performance. In his later years this took the form of imagined conspiracies against him by friend and foe alike. He possessed an imperious disposition that reveled in giving orders, filing complaints, and seeking satisfaction. A military career was probably best suited to his talents, but even here he went too far. For example, General Washington thought that his vendetta with Major Reid was trifling and smacked of persecution. It is not surprising that Hazen was at the center of several courts – martial; what is surprising is that he was not involved in any duels.

All of these characteristics were magnified by his illness. His enforced physical inactivity added to his frustrations. It was galling to have to rely on others to carry out his instructions, which were never performed to his satisfaction. His projects became more unrealistic with the passage of time. Torrey found him erratic, talking “every day more oddly.” During his last months a court found him of unsound mind.

The career of Moses Hazen is one of the tragedies of the Revolutionary era. A man of marked abilities and great drive was prevented by circumstances and his own temperament from achieving his aspirations. A buccaneer in an age of buccaneers, he might after the war have become one of the great colonizers of his generation- at Detroit, in northern New York, or in the Coos Country. Instead, his health gave way and his vast dreams came to nothing.

Nevertheless, he made a notable contribution to the American Revolution by mobilizing and leading its Canadian sympathizers, fighting for their rights and prerogatives, and heading the drive to get them onto lands of their own in the United States. These are no small achievements.

Bounty Land Area for Hazens Regiment

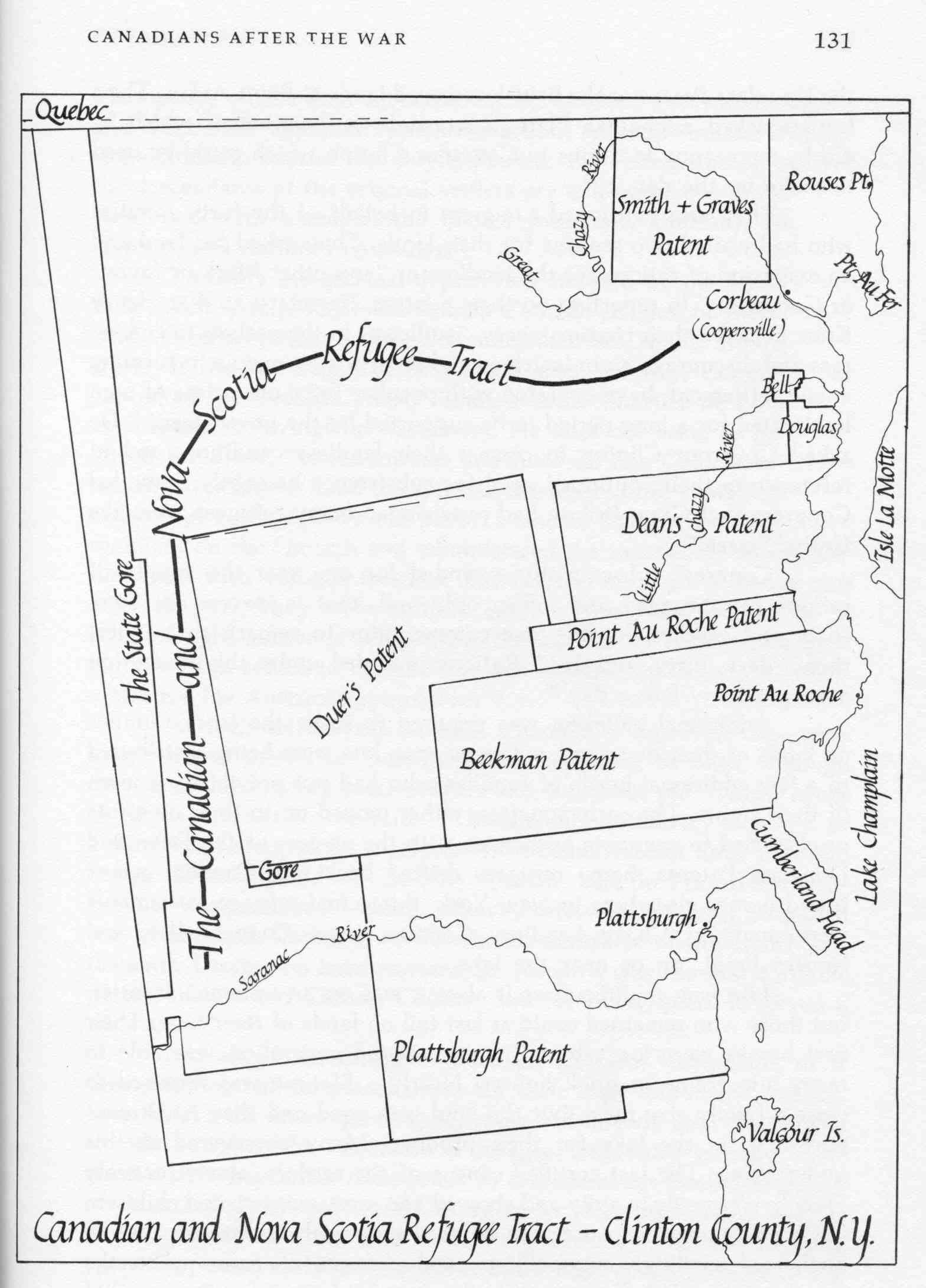

One of the many difficulties experienced by the Revolutionary War veterans of Hazens Regiment was in obtaining the land promised them in their Bounty Land Warrants. After a convoluted and protracted process involving Congress and the State of New York, at least some members of the Regiment, and some of the Canadian refugees, apparently received land on the western shore of Lake Champlain in Clinton County, New York. A map of the land patents in this area is shown in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6. Canadian and Nova Scotia Refugee Tract – Clinton County, N.Y., (from Everest1, p. 131). Apparently members of Hazens Regiment finally obtained land in and around the Beekman, Bell and Douglas Patents.

Everest1 provides the following description of one of the efforts of the veterans and refugees associated with Hazens Regiment:

Impatient with all the delays, a few of the refugees began to gravitate toward northern New York immediately after the war. In the summer of -1783, eleven of them accompanied Lieutenant Benjamin Mooers to Point au Roche in the Beekman Patent. Here they made a small settlement, sometimes known as Hazenburgh after its sponsor, Moses Hazen, for whom Mooers served as agent. Among their number were Jean La Framboise and two Montys, eager to reclaim the farms they had established before the Revolution and had to abandon in 1776. Over the next two years others squatted on sites along the shore north from Point au Roche, mostly on Dean’s Patent, so as to be nearby when their own lands were available, and perhaps to exchange them for their squatters’ claims.

Many of the veterans and others who obtained bounty land warrants sold them at a discount to land speculators rather than receiving their land, in many cases because of the long delays. It is unknown whether William Grimshaw received land, cash or other value for his warrant. It is known from census records, however, that he lived for many years (until at least 1810) in New Hampshire rather than New York.

John Grimshaw, Another Revolutionary War Veteran

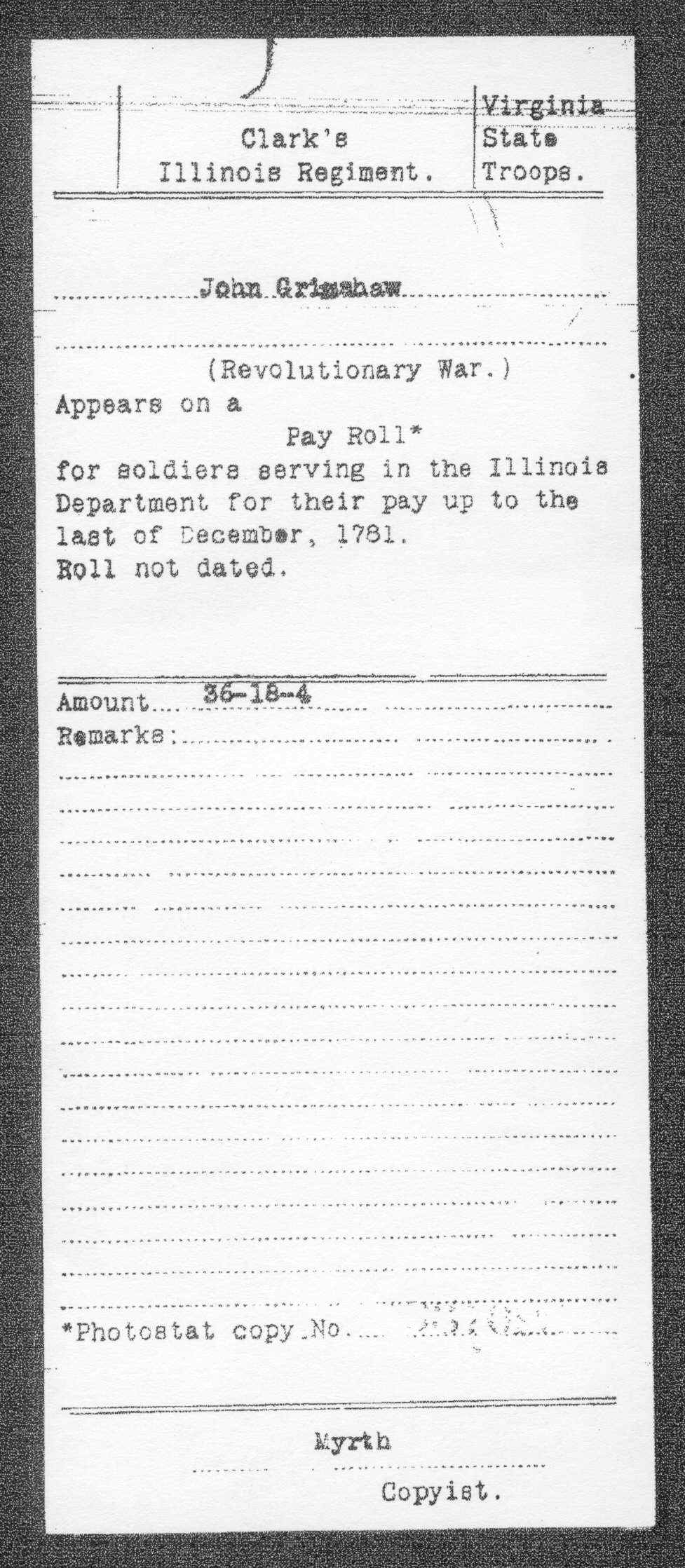

John was another Grimshaw who served in the Revolutionary War. An entry for him in the Compiled Service Record2 indicates that he served in Clarks Illinois Regiment of the Virginia State Troops (see Figure 7 below). It is not known if his ancestors and descendants have been researched.

Figure 7. John Grimshaw Revolutionary War service record, showing service in Clarks Illinois Regiment. The record is shown on the left, and the jacket containing the record is on the right.

References

1

Everest, Allan S., 1976, Moses Hazen and the Canadian Refugees in the American Revolution: Syracuse, NY, Syracuse University Press, 217 p.

2

National Archives Microfilm Publications no. M881, 1972, Roll 83 – Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army during the Revolutionary War, Continental Troops, Hazen’s Regiment, G.

3

National Archives Microfilm Publications no. M246, 1957, Roll 132 – Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, Continental Troops Jacket Numbers 208 through 218-2: A list of names of Col. Moses Hazen’s (2d Canadian) Regt. made in 1783 for the Secretary of Treasury.

4

National Archives Microfilm Publications no. M804, 1969, Roll 1136 – Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application File, Grimke, John Faucheraud – Grist, Jacob: Copy of William’s Bounty Land Warrant Record Card, Warrant Number 13129.

5National Archives Microfilm Publications no. M829, Roll 11 – US Revolutionary War Bounty Land Warrants Used in the US Military District of Ohio (Acts of 1788, 1803, and 1805.)

6“Bounty System” Encyclopædia Britannica Online. <http://members.eb.com/bol/topic?eu= 16158&sctn=1> [Accessed 17 December 2000].

7White, Virgil D., abstracter, 1991, Genealogical Abstracts of Revolutionary War Pension Files, v. II, F-M: Waynesboro, Tennessee, The National Historical Publishing Co., unk p.

8U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1907, Heads of Families at the First Census of the U.S. Taken in the Year 1790, New Hampshire: Spartansburg, SC, The Reprint Co., 146 p.

9 Threlfall, John B., 1973, Heads of Families at the Census of the U.S. Taken in the Year 1800, New Hampshire: Chicago, IL, Adams Press, 222 p.

10Jackson, Ronald Va., G.R. Teeples, and D. Schafenmeyer, 2976, New Hampshire 1810 Census Index: Bountiful, UT, Accelerated Indexing Systems, Inc., 86 p.

Webpage History

Webpage posted December 2000, updated March 2001. Updated March 2012 with change of banner. Updated February 2013 with discounting William as the son of Johan and Hannah (Fieldhouse) Grimshaw