“Dark Mysteries of Papua”

A New York Times Magazine Article by Beatrice Grimshaw February 4, 1923

Beatrice Grimshaw was an adventurer and author who spent most of her life in the South Pacific; she is the subject of a companion webpage on this website. In 1923 she published an article on Papua in the New York Times Magazine based on her travels and previous extensive works. This article is reproduced on this webpage with added background information.

Contents

“Dark Mysteries of Papua” by Beatrice Grimshaw

Webpage Credits

Thanks go to the New York Times for making this article available on its website.

“Dark Mysteries of Papua” by Beatrice Grimshaw

No doubt much of the information presented in this article is derived from Beatrice’s extensive previous publications on New Guinea and the South Pacific in general. The article is provided below generally as published in the New York Times Magazine. A PDF file of the original article is provided below.

Note: some, but not all, of the segments have one line of overlap. This may be confusing at first.

PDF File of Original Article

The New York Times website has made this article available on its website at the address shown below. The PDF from the website can be viewed by clicking here.

Background Information on New Guinea from Wikipedia

A portion of the Wikipedia information on New Guinea is provided below as background information for Beatrice’s article.

New Guinea

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

New Guinea, located just north of Australia, is the world’s second largest island, having become separated from the Australian mainland when the area now known as the Torres Strait flooded around 5000 BC. The name Papua has also been long-associated with the island (see “History”, below). The western half of the island contains the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Irian Jaya, while the eastern half forms the mainland of the independent country of Papua New Guinea.

At 4,884 metres, Puncak Jaya (sometimes called Mount Carstensz) makes New Guinea the world’s fourth highest landmass.

Political Divisions

The island of New Guinea is divided politically into roughly equal halves across a north-south line:

The western portion of the island (Irian in Indonesian), located west of 141°E longitude, (except for a small section of territory to the east of the Fly River which belongs to Papua New Guinea) was formerly a Dutch colony and is now incorporated into Indonesia as the provinces:

West Irian Jaya (Irian Jaya Barat) with Manokwari as its capital. A name change to “West Papua” is currently in progress and awaiting final approval and regulation.[citation needed]

Papua (formerly Irian Jaya) with the city of Jayapura as its capital. A proposal to split this province into Central Papua (Papua Tengah) and East Papua (Papua Timur) has not been implemented.

(See also Western New Guinea, which refers to the entire western half of New Guinea)

The eastern part forms the mainland of Papua New Guinea, which has been an independent country since 1975. It was formerly a territory governed by Australia.

History

The first inhabitants of New Guinea arrived at least around 40,000 years ago, having travelled through the south-east Asian peninsula. These first inhabitants, from whom the Papuan people are probably descended, adapted to the range of ecologies and in time developed one of the earliest known agricultures. Remains of this agricultural system, in the form of ancient irrigation systems in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, are being studied by archaeologists. This work is still in its early stages so there is still uncertainty as to precisely what crop was being grown, or when/where agriculture arose.

The gardens of the New Guinea highlands are ancient, intensive permacultures, adapted to high population densities, very high rainfalls (as high as 10,000 mm/yr (400 in/yr)), earthquakes, hilly land, and occasional frost. Complex mulches, crop rotations and tillages are used in rotation on terraces with complex irrigation systems. Western agronomists still do not understand all practices, and native gardeners are notably more successful than most scientific farmers.[citation needed] Some authorities believe that New Guinea gardeners invented crop rotation well before western Europeans.[citation needed] A unique feature of New Guinea permaculture is the silviculture of Casuarina oligodon, a tall, sturdy native ironwood tree, suited to use for timber and fuel, with root nodules that fix nitrogen. Pollen studies show that it was adopted during an ancient period of extreme deforestation.

In more recent millennia another wave of people arrived on the shores of New Guinea. These were the Austronesian people, who had spread down from Taiwan, through the south-east Asian archipelago, colonising many of the islands on the way. The Austronesian people had technology and skills extremely well adapted to ocean voyaging and Austronesian language speaking people are present along much of the coastal areas and islands of New Guinea.

The first European contact with New Guinea was by Portuguese and/or Spanish sailors in the 16th century. In 1526-27 Don Jorge de Meneses saw the western tip of New Guinea and named it ilhas dos Papuas. Ploeg[2] reports that the word papua is often said to derive from the Malay word papua or pua-pua, meaning ‘frizzly-haired’, referring to the highly curly hair of the inhabitants of these areas. Another possibility, (put forward by Sollewijn Gelpke in 1993) is that it comes from the Biak phrase sup i papwa which means ‘the land below [the sunset]’ and refers to the islands west of the Bird’s Head, as far as Halmahera.

Whatever the origin of the name Papua, it came to be associated with this area, and more especially with Halmahera, which was known to the Portuguese by this name during the era of their colonisation in this part of the world.

In 1545 the Spaniard Yñigo Ortiz de Retez sailed along the north coast of New Guinea as far as the Mamberamo River near which he landed, naming the island ‘Nueva Guinea’. The first map showing the whole island (as an island) was published in 1600 and shows it as ‘Nova Guinea’.

The first European claim occurred in 1828, when the Netherlands formally claimed the western half of the island as Netherlands New Guinea. In 1883, following a short-lived French annexation of New Ireland, the British colony of Queensland annexed south-eastern New Guinea. However, the Queensland government’s superiors in the United Kingdom revoked the claim, and (formally) assumed direct responsibility in 1884, when Germany claimed north-eastern New Guinea as the protectorate of German New Guinea (also styled Kaiser-Wilhelmsland). The first Dutch government posts were established in 1898 and in 1902 Manokwari on the North coast, Fak-Fak in the West and Merauke in the South at the border with British New Guinea.

Both the Dutch and the British tried to suppress warfare and headhunting once common between the villages of the populace.

In 1905 the British government renamed their territory to Papua and in 1906 transferred total responsibility for it to Australia. During World War I, Australian forces seized German New Guinea, which in 1920 became a League of Nations mandated territory of Australia. The Australian territories became collectively known as The Territories of Papua and New Guinea (until February 1942).

Before about 1930, most European maps showed the highlands as uninhabited forests. When first flown over by aircraft, numerous settlements with agricultural terraces and stockades were observed. The most startling discovery took place on August 4, 1938, when Richard Archbold discovered the Grand Valley of the Balim River which had 50,000 yet-undiscovered Stone Age farmers living in orderly villages. The people, known as the Dani, were the last society of its size to make first contact with the western world.[3]

During the 1950s the Dutch government began to prepare Netherlands New Guinea for full independence and allowed elections in 1959; an elected Papuan council, the New Guinea Council (Nieuw Guinea Raad) took office on April 5, 1961. The Council decided on the name of West Papua, a national emblem, a flag called the Morning Star or Bintang Kejora, and a national anthem; the flag was first raised — next to the Dutch flag — on December 1, 1961. However, Indonesia threatened with an invasion, after full mobilisation of its army, by August 15, 1962, after receiving military help from the Soviet Union. Under strong pressure of the United States government (under the Kennedy administration) the Dutch, who were prepared to resist an Indonesian attack, attended diplomatic talks. On October 1, 1962, the Dutch handed over the territory to a temporary UN administration (UNTEA). On May 1, 1963, Indonesia took control. The territory was renamed West Irian and then Irian Jaya. In 1969 Indonesia, under the 1962 New York Agreement, was required to organize a plebiscite to seek the consent of the Papuans for Indonesian rule. This so called Act of Free Choice (Pepera) resulted, under strong threats and intimidations of the Indonesian military, in a 100% vote for continued Indonesian rule.

From 1971, the name Papua New Guinea was used for the Australian territory. On September 16, 1975, Australia granted full independence to Papua New Guinea.

In 2000, amid increasing discontent and opposition to Indonesian rule, Irian Jaya was formally renamed “The Province of Papua” and a large measure of “special autonomy” was granted in 2001. This law on special autonomy, however, was never implemented. On the contrary, at the beginning of 2003 President Megawati Sukarnoputri announced the division of the province into three parts, while the name “Papua” for the province would again revert to Irian. With strong public protest by Papuans, only the province of West Irian Jaya (with Manokwari as its capital and covering the Bird’s Head peninsula) was split from Papua Province. In 2005 a new proposal came from Jakarta to split the province into five provinces. This plan has not yet been implemented.

Cannibalism

New Guinea is well-known in the popular imagination for supposed ritual cannibalism that was apparently practiced by some (but far from all) ethnic groups. The Korowai and Kombai peoples of southeastern Papua are two of the last surviving tribes in the world said to have engaged in cannibalism in the recent past. In the Asmat area of southwestern Papua, it may have occcured up until the early 1970s. In a 2006 episode of the documentary series “Going Tribal”, a Kombai man recounts his participation in cannibal rituals.[1] In 1963, a missionary named Tom Bozeman described the Dani tribe feasting on an enemy slain in battle. [2] New Guinea cannibalism has also been described in fictional works such as the novel Cryptonomicon by Neal Stephenson.

According to Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, cannibalism may have arisen in New Guinea due to the scarcity of sources of protein. The traditional crops, taro and sweet potato, are low in protein compared to wheat and pulses, and the only edible animals available were small and unappetizing, such as mice, spiders, and frogs. Cannibalism led to the spread of kuru, prompting the Australian administration to outlaw the practice in 1959.

During WWII, Japanese soldiers cannibalized each other, fallen Allied soldiers, and natives of the island in order to elude starvation.

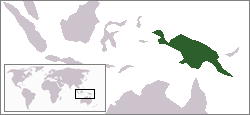

Where is Papua New Guinea?

The island of New Guinea is in the South Pacific, just north of Australia. Wikipedia has made the following maps available showing the location and the subdivisions of New Guinea, including Papua New Guinea, and independent country, on the eastern portion of the island. The two provinces on the western part of the island are part of Indonesia.

References

1Grimshaw, Beatrice, 1923, Dark Mysteries of Papua: New York Times Magazine, February 4, 1923, page SM6.

2Author

Webpage History

Webpage posted March 2007. Updated February 2010 with banner replacement.