Walter Grimshaw, Superior Amateur Chess Player

and Chess Problem Developer from Yorkshire

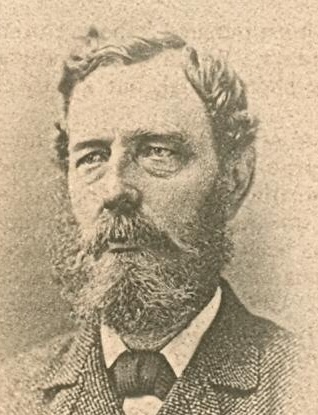

Walter Grimshaw’s Photo and Signature

Source: http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/winter86.html#7271._Walter_Grimshaw

(Note: Webpage in preparation)

Walter Grimshaw was a chess problem developer who was considered one of the foremost amateur chess players in England during his lifetime. He won the first chess problem competition ever held (in 1854), and he developed a chess device, termed the “Grimshaw” that remains well known and is frequently played to this day. Walter Grimshaw defeated the presiding world chess champion, Wilhelm (later William) Steinitz, in the 1870s with just 17 moves in “the most summary demolishment of Steinitz on record”. Steinitz disputed the date of the game (December 30, 1870) and the 17-move record, but he did not deny his defeat at Grimshaw’s hands.

Walter was born in Rawdon, Yorkshire on September 2, 1832 (or March 12 as stated on his gravestone) to James and Mary (Hague) Grimshaw. James was apparently not from the Rawden and Guiseley area (where he married Mary Hague), but was from Daventry, near Northampton. If so, he was not likely to be a descendant of the prominent Edward and Dorothy (Raner) Grimshaw line (see companion webpage) of the Rawdon area. Walter married Mary Holliday at Saint Crux’s Church in York on October 9 or 10, 1861, and the couple had one son, Walter Edwin Grimshaw, born at Whitby on August 21, 1862. They had a second child, Mary, born on October 20, 1868, but she died less than a year later, on September 1, 1869. The mother, Mary, died just 10 days after the birth of her daughter, on October 30. A family of origin for Walter in the Rawdon and Guiseley area near Leeds and in the Daventry area near Northampton has been tentatively identified.

Walter Grimshaw was apprenticed as a pawnbroker as a youth and took over an established business of that type in Whitby. However, his business interests expanded to include shipping and partial ownership of steamboats, and he became well off. He apparently married a second time, but his wife became an invalid. At age 58, Walter became despondent and his mind became “unhinged”. He committed suicide on December 27, 1890 and is buried with his first wife and infant daughter in Whitby.

Contents

Photographs of Walter Grimshaw

Walter Grimshaw and the Grimshaw “Chess Problem” on Wikipedia

Walter Grimshaw Defeated World Chess Champion Wilhelm Steinitz

Report on Walter Grimshaw on “Chess History” Website

Family Information for Walter Grimshaw

Newspaper Article on Walter Grimshaw’s Suicide

Final Resting Place of Walter and His First Wife, Mary

Webpage Credits

None yet…

Photographs of Walter Grimshaw

Walter Grimshaw and the Grimshaw “Chess Problem” on Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Grimshaw

Walter Grimshaw

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Walter Grimshaw was a 19th century composer of chess problems. In 1854 he won the first ever chess problem solving competition in London. He is perhaps best known for giving his name to the Grimshaw, a popular problem theme.

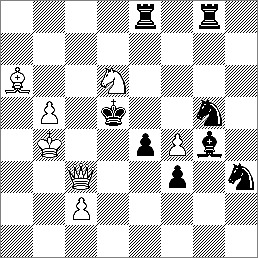

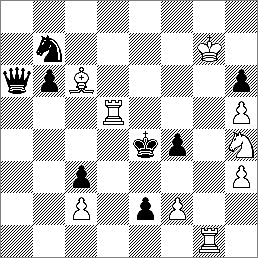

This is one of his problems, a mate in five (white moves first, and must checkmate black within five moves against any defence) first published in the Illustrated London News in 1850. The key (see chess problem terminology) is 1.Bc8 (see algebraic notation) which threatens 2.Qc5# or Qd2#. To defend, black plays 1…Bxc8 white plays 2.Qf6 (threatening 2…c4#) and now a Grimshaw interference comes into play: black can defend by cutting off the white queen from the defence of d6 with 2…Ne6 or 2…Be6, but this interferes with the rook’s guard of e5, and so allows 3.Qe5#. If instead black plays 2…Re6, this interferes with the bishop’s guard of f5 which is significant after 3.Qd4+ Kxd4 4.Nf5+, because the knight cannot be captured. Instead, there follows 4…Kd5 5.c4#.

This is one of Grimshaw’s better known problems, a mate in three composed for a compitition organised by the Chess Players Chronicle, 1852-54. The key is the paradoxical 1.Rf1, sacrificing a strong white piece. This carries the threats 2.Nf3 (leading to various mates delivered by the d5 rook) and 2.f3+ (leading to knight mates on f5 or g2). Black’s obvious defence, 1…exf1Q is answered by 2.Nf3 Kxf3 3.Rd2#. After 1…f3 (giving black a flight at f4), white plays his rook back to where it came from (a switchback) to take advantage of the newly opened fourth rank: 2.Rg1 any 3.Rg4#

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grimshaw

Grimshaw

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

A Grimshaw is a device found in chess problems in which two black pieces arriving on a particular square mutually interfere with each other. It is named after the 19th century problem composer Walter Grimshaw.

The theme can be understood by reference to the following example by A. G. Corrias (published in Good Companion, 1917):

The problem is a mate in two (white must move first and checkmate black in two moves against any defence). The key (see chess problem terminology) is 1.Qb1 (see algebraic notation), which threatens 2.Qb7#. Black has three ways to defend against this. One is to play 1…c3, giving his king a new flight square at c4, but this unguards d3, allowing white to mate with 2.Qd3#. It is the other two black defences, however, which show the Grimshaw theme.

Black can play 1…Bb2, thus cutting off the white queen’s path to b7. However, the bishop on b2 interferes with the a2 rook and stops it moving along the rank – this allows white to play 2.Qh1# (after a different black move, this would not be possible because of 2…Rg2, blocking the check).

Black can instead play 1…Rb2, cutting of the white queen with the rook rather than the bishop. However, just as the bishop on b2 interferes with the rook, so the rook on b2 interferes with the bishop, allowing white to play 2.Qf5# (a mate not otherwise possible, because of 2…Be5, blocking the check).

It is this mutual interference between two black pieces on the one square (in this case, a rook and a bishop on b2) which constitutes a Grimshaw.

The Grimshaw is one of the most common devices found in directmates. The pieces involved are usually rook and bishop, as in the above example, although Grimshaws involving pawns are also seen, as in this mate in two example by Frank Janet (published in the St.Louis Globe Democrat, 1916):

The key is 1.Qd7, threatening 2.Qf5#. As in the previous example, black can defend by cutting white’s queen off from its intended destination square, but two of these defences have fatal flaws in that the interfere with other pieces: 1…Be6 interferes with the pawn on e7, allowing 2.Qxc7# (2…e5 would be possible were the bishop not on e6) and 1…e6 interferes with the bishop, allowing 2.Qxa4# (2…Bc4 would be possible were the pawn not on e6). It is this mutual interference between bishop and pawn on e6 which constitutes the pawn Grimshaw (there are several other non-thmatic black defences in this problem – click the diagram for them all).

Sometimes, multiple Grimshaws can be combined in the one problem. Here are two examples by Lev Ilych Loshinsky each with three Grimshaws:

This was first published in L’Italia Scacchistica, 1930. It is a mate in two. The key is 1.Rb1, with the threat 2.d4#. Each of black’s defences produces a Grimshaw interference which stops him from capturing white’s mating piece. Black’s defences, with white’s replies, are:

1…Re6 2.Nd7# (2…Bxd7 not possible)1…Be6 2.Bd6# (2…Rxd6 not possible)1…Rg4 2.Ne6# (2…Bxe6 not possible)1…Bg4 2.Bg1# (2…Rxg1 not possible)1…Rb2 2.Qxc3# (2…Bxc3 not possible)1…Bb2 2.Qf2# (2…Rxf2 not possible)

There is one other black defence: 1…Rd6 leading to the simple recapture 2.Bxd6# (this is essentially the same mate as that which follows 1…Be6).

This second Loshinsky example, also a mate in two, is from Tijdschrift v.d. Nederlandse Schaakbond, 1930, and is one of the most famous of all chess problems. It is a complete block (if white could pass his first move, then he could reply to every black move with a mate), and white’s key, 1.Bb3, holds this block, making no threat, but putting black in zugzwang. Black has six defences leading to three Grimshaws, one of them a pawn Grimshaw:

1…Rb7 2.Rc6# (2…Bxc6 not possible)1…Bb7 2.Re7# (2…Rxe7 not possible)1…Rg7 2.Qe5# (2…Bxe5 not possible)1…Bg7 2.Qxf7# (2…Rxf7 not possible)1…Bf6 2.Qg4# (2…f5 not possible)1…f6 2.Qe4# (2…Bxe4 not possible)

After other black moves, white can play one of the above moves to mate; the three exceptions are 1…f5, taking away that square from the king and allowed 2.Qd6# and two recaptures: 1…Rxc7 2.Nxc7# and 1…Bxd4 2.Nxd4#.

A close relative of the Grimshaw is the Novotny, which is essentially a Grimshaw brought about by a white sacrifice on a square where it can be captured by two different black pieces – whichever black piece captures the white piece, it interferes with the other.

Walter Grimshaw Defeated World Chess Champion Wilhelm Steinitz

See: http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/grimshawsteinitz.html

Steinitz on Wikipedia…

Wilhelm (later William) Steinitz (Prague, May 17, 1836 – August 12, 1900) was an Austrian and then American chess player and the first undisputed world chess champion from 1886 to 1894. From the 1870s onwards, commentators have debated whether Steinitz was effectively the champion earlier. Steinitz lost his title to Emanuel Lasker in 1894 and also lost a rematch in 1897.

Statistical rating systems give Steinitz a rather low ranking among world champions, mainly because he took several long breaks from competitive play. However, an analysis based on one of these rating systems shows that he was one of the most dominant players in the history of the game. As author Will Hartson wrote in his chess historical, Steinitz was unbeaten in over 25 years of match play. He was perhaps the first of the modern champions, and established a greater depth in playing.

Although Steinitz became “world number one” by winning in the all-out attacking style that was common in the 1860s, he unveiled in 1873 a new positional style of play and demonstrated that it was superior to the previous style. His new style was controversial and some even branded it as “cowardly”, but many of Steinitz’s games showed that it could also set up attacks as ferocious as those of the old school. Steinitz was also a prolific writer on chess, and defended his new ideas vigorously. The debate was so bitter and sometimes abusive that it became known as the “Ink War”. By the early 1890s, Steinitz’s approach was widely accepted and the next generation of top players acknowledged their debt to him, most notably his successor as world champion, Emanuel Lasker.

As a result of the “Ink War”, traditional accounts of Steinitz’s character depict him as ill-tempered and aggressive; but more recent research shows that he had long and friendly relationships with some players and chess organizations. Most notably from 1888 to 1889 he co-operated with the American Chess Congress in a project to define rules governing the conduct of future world championships. Steinitz was unskilled at managing money and lived in poverty all his life.

Report on Walter Grimshaw on “Chess History” Website

- Walter Grimshaw (1832-1890)

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) sends a photograph, taken by Steve Mann, of Walter Grimshaw’s gravestone in the Larpool Lane Cemetery, Whitby, England:

A note by Mr Mann:

‘The original interment was of Walter Grimshaw’s first wife, Mary, whom he had married in York (St Crux) on 10 October 1861. She died soon after giving birth to their second child, Mary, who died within a year. Earlier, Walter and Mary had had a son, Walter Edwin Grimshaw, who survived his father. The latter’s second wife was the widow Jane Trattles, of the ship-owning company Trattles. They married on 18 May 1878 at Whitby parish church.’

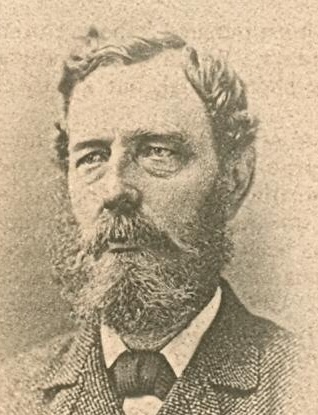

On 27 December 1890 Grimshaw committed suicide by cutting his throat with a razor. Mr McDowell has sent us the lengthy account published on page 5 of the Whitby Times, 2 January 1891.The photograph referred to in the Whitby Times is reproduced below (the frontispiece to the January 1886 BCM):

A further photograph of Grimshaw was published opposite page 41 of the February 1891 BCM:

As regards the Grimshaw theme (reciprocal interferences between two pieces of unlike motion), Mr McDowell notes that Grimshaw’s famous problem first appeared in the Illustrated London News of 24 August 1850:

Mate in five

Our correspondent adds:

‘The first edition of the Oxford Companion to Chess (page 134) gives the correct publication year of the problem (1850), while the second edition (page 99) gets it wrong.’

We note the following in the entry on the Grimshaw theme on pages 172-173 of the Dictionnaire des échecs by F. Le Lionnais and E. Maget (Paris, 1967):

‘Le problème souche est attribué à Walter Grimshaw (mais il est en réalité de Brede qui avait fait apparaître, sans s’en rendre compte il est vrai, une “Interception Grimshaw”, en 1844, dans une variante secondaire. Grimshaw, en 1850, composa délibérément le premier problème sur ce thème).’

Henry E. Kidson wrote about Grimshaw in ‘Some reminiscences of a noted problem composer’ in the Yorkshire Weekly Post, an article which was reproduced on pages 38-39 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, November-December 1906. Grimshaw and Kidson both appear in a photograph (Redcar, 1866) given in C.N. 5614.

Source: http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/winter86.html#7271._Walter_Grimshaw

Family Information for Walter Grimshaw

Summary of information from FamilySearch.org and Chess History website…

Born September 2, 1832 at Rawdon to James and Mary Grimshaw. (This date is not consistent, however, with Walter’s headstone date of March 12, 1832.)

Married Mary Holliday, daughter of Thomas Holliday, at St Crux, Yorkshire on October 9 or 10, 1861

Recorded in 1861 census living in Whitby

First child, Walter Edwin Grimshaw, born at Whitby on August 21, 1862

Second child, Mary, born at Whitby on October 20, 1868, but died in infancy on September 21, 1869

First wife Mary died 10 days after giving birth, on October 30, 1868

Walter Grimshaw’s family of origin tentatively identified from the Bean family website, as interpreted. Walter’s father, James, was apparently one of three Grimshaw brothers lived in the Northampton area at Daventry, Staverton, and Barby.

James Grimshaw must have moved to Guiseley near Leeds and married Mary Hague. (Conversion to Quakerism?) If so, Walter Grimshaw is descended from a different Grimshaw line from the Edward and Dorothy (Raner) line.

Source: http://www.beanweb.net/ft/bean/pafg387.htm

Walter is fourth of seven children as shown below. Names of parents are correct, location is suitable, and birthdate is satisfactory (although not consistent with gravestone). James and Mary Hague were married in Guiseley, close to Rawdon, Walter’s birthplace.

Unknown Grimshaw & Unknown

|–James Grimshaw (ca 1798, Daventry, Northamptonshire – ?) & Mary Hague (ca 1803, Horsforth, Yorkshire). Mar. 28 Nov 1824, Guiseley, Yorkshire.

|–|–Edward Grimshaw (ca 1826, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–Elizabeth Grimshaw (ca 1829, Yorkshire – ?) & Thomas Pheasant. Mar 1852, Dewsbury, Yorkshire.

|–|–|–James Pheasant (ca 1854, York, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|–Mary Pheasant (ca 1852, High Town, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|–Thomas Pheasant (ca 1859, Pontrefract, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|–George Walter Pheasant (ca 1860, Pontrefract, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|–Edward Pheasant (ca 1869, Brihourse, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–George “James” Grimshaw (ca 1831, Dewsbury, Yorkshire – ?) & Margaret Jackson (ca 1842, Eskdaleside, Yorkshire – ?). Mar. 1868, Whitby, Yorkshire.

|–|–|– James Grimshaw(1870, High Town, Liversedge, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|– Basil Grimshaw (ca 1874, Liversedge, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–Walter Grimshaw (ca 1833, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–Hannah Grimshaw (ca 1836 – ?)

|–|–Mary Ann Grimshaw (ca 1839, Cleckheaton, Yorkshire – ?) & Isaac Jackson (ch 21 Oct 1838, Whitby – 1859, Whitby). Mar. 1859, Whitby.

|–|–Emma Grimshaw (ca 1842, Liversedge, Yorkshire – ?)

Probable brother…

|– John Grimshaw (ca 1791, Staverton, Northamptonshire – ?) & Sarah Jackson (ca 1792, Stevenage, Herefordshire). Married 19 Dec 1813, All Saints, Northamptonshire.

|–|–John Samuel Grimshaw (ch 30 Oct 1814, Kilsby, Northamptonshire – ?) & Elizabeth Stott (ca 1819, Dewsbury, Yorkshire – ?). Married 1837, Dewsbury, Yorkshire.

|–|–|–Frank Jackson Grimshaw (ch 22 Jul 1838, Dewsbury, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|–Ann Ellen Grimshaw

|–|–|–John Alfred Grimshaw (ca 1842, Derby – ?)

|–|–|–Louisa Grimshaw (ca 1848, Retford Nottinghamshire – ?)

|–|–|–George Grimshaw (ca 1851, York, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|–Thomas Grimshaw (ca 1854, York, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|–Kate Grimshaw (ca 1856, York, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|–Ada Grimshaw (ca 1856, York, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–Elizabeth Jackson Grimshaw (ch 23 Dec 1819, All Saints, Northampton – 1885, York, Yorkshire & William Shaw (ca 1823, York, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–|– Lewis Shaw (ca 1848, York, Yorkshire – ?)

|–|–Thomas William Grimshaw (ca 1824, Northamptonshire – 12 Feb 1875, Leeds)

|–|–Louisa Sarah Grimshaw (ch 5 Feb 1823, All Saints, Northampton – ?)

Another probable brother; see note at bottom

|–William Grimshaw (bef 1800 – bef 1841) & Jane Wood? (ca 1791, Barby, Northamptonshire – ?)

|–|–William Grimshaw (ch 5 Dec 1813, Barby)

|–|–Jane Grimshaw (ch 22 Jun 1817, Barby)

|–|–Thomas Grimshaw (ch 12 Sep 1819, Barby)

|–|–Harriett Grimshaw (ch 29 Oct 1820, Barby)

|–|–Sarah Grimshaw (ch 4 May 1823, Barby)

|–|–James Grimshw (ch 29 Jan 1826, Barby)

|–|–Elizabeth Grimshaw (ch 24 Feb 1828, Barby)

|–|–Anne Grimshaw (ch 16 May 1830, Barby)

“Probably a brother of John & James Grimshaw of Daventry, Northamptonshire. Possibly had another brother, Caleb, who had a daughter, Mary, at Ringstead, Northants in 1814. Ringstead is 26 miles from Daventry.”

Newspaper Article on Walter Grimshaw’s Suicide

Click here for upper half of the article.

Click here for the lower half.

Final Resting Place of Walter and His First Wife, Mary

“Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) sends a photograph, taken by Steve Mann, of Walter Grimshaw’s gravestone in the Larpool Lane Cemetery, Whitby, England”:

Webpage History

Webpage posted January 2005. Updated May 2012 with addition of photos and gravestone picture