Mary Grimshaw, “Charwoman” to King Charles II on the Island of Jersey

King

Charles II

During the English Civil Wars in the 1600s, Charles II twice stayed in Elizabeth Castle on Jersey, one of the Channel Islands. During his second visit, and possibly also during the first, Charles received the services of Mary Grimsha as his “Necessary Woman” — apparently she kept his quarters clean. Marys services were recorded in a small document that is still in existence; it is dated February 12, 1650 (current calendar convention.)

Contents

Document Showing Mary Grimsha’s Services to Charles II

Margaret Toynbee’s Article on Mary Grimsha

Marjorie Grimshaw’s Research into Mary Grimsha

Why Was the King of England Staying on the Small Island of Jersey?

Description of Charles II’s Visits to Jersey

Webpage Credits

Thanks go to Marjorie Grimshaw, resident of Jersey, for finding the Mary Grimsha records and for contributing the most relevant information on this webpage.

Document Showing Mary Grimsha’s Services to Charles II

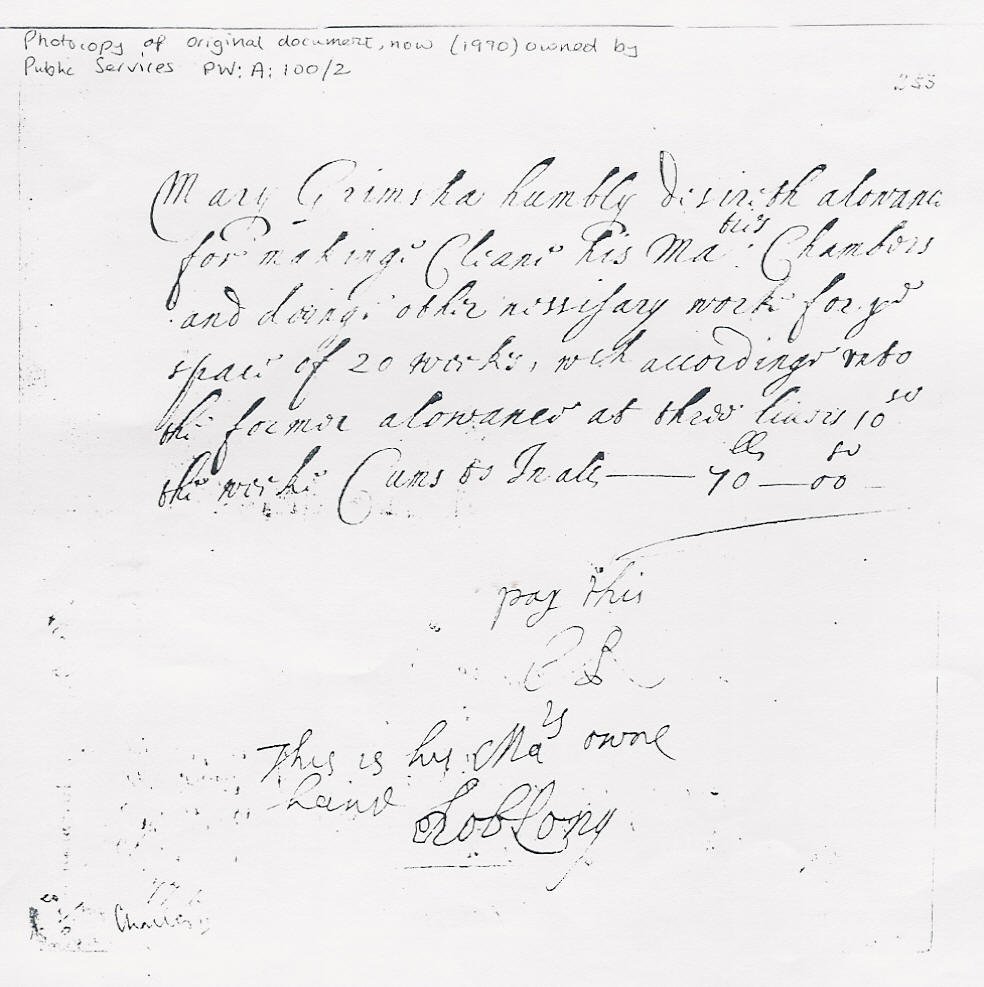

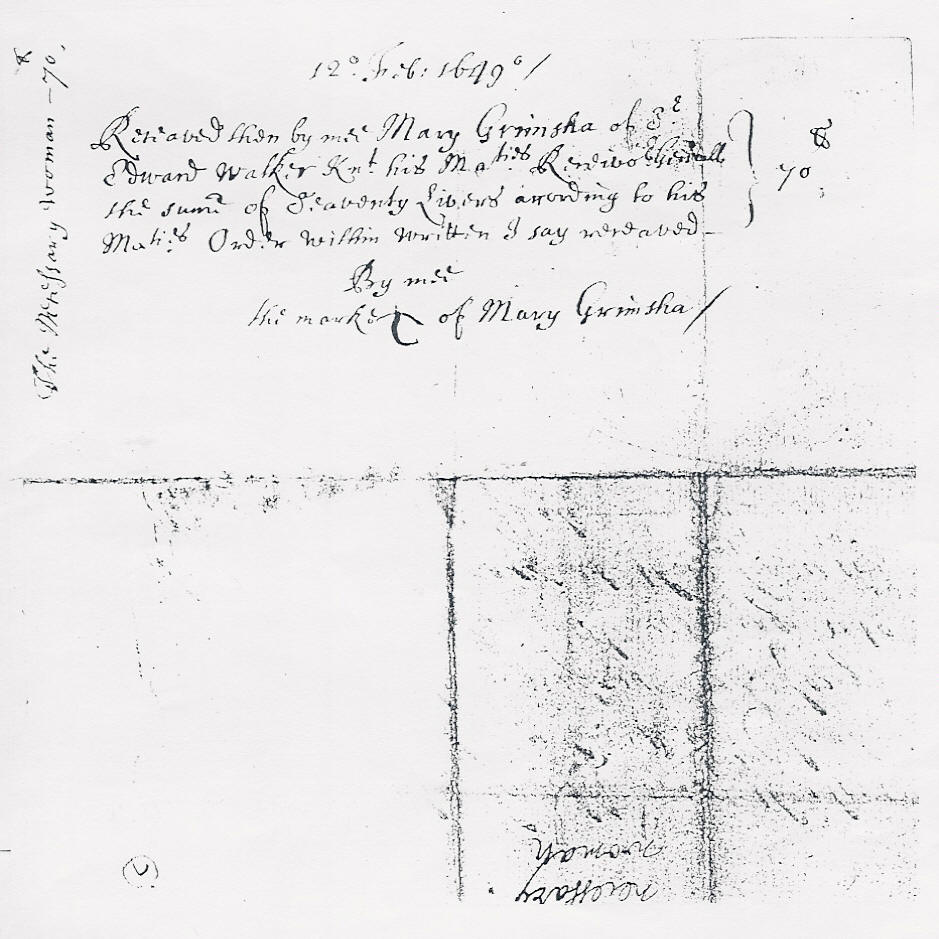

The record of Marys services to King Charles II is an invoice or petition for payment in the amount of 70 lbs (Figure 1.) The petition has written on it an annotation by the King (in his own hand), “Pay this.” On the back of the document is a receipt for the payment and two additional annotations (Figure 2.)

Figure 1. Front view of document showing application for payment for Mary Grimshas services as Charles IIs “Necessary woman.” The text is shown below Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 2. Back view of document, showing record of payment of the amount due. The text is described below the image.

Margaret Toynbee’s Article on Mary Grimsha

The significance of the document showing Mary Grimshas services, the Kings approval, and the receipt for payment were well described by Margaret Toynbee in a short article1 published in 1944 — the text of the article is shown below:

KING CHARLES “CHARWOMAN.”

UNDER the above title there was recently offered for sale a document upon which, by the courtesy of its purchaser, Mr. J. Boehrer Charles, of Harrogate, who has also very kindly supplied me with the full description set out below, I am permitted to contribute the following notes. The document runs:- “Mary Grimsha humbly desireth alowance for making cleane his Maties Chambers and doinge other nessifary work for ye space of 20 weekes, wch. accordinge unto the former alowance of three livers 10se the wirke Cums to In all – 70lbs – 00se.” The account is endorsed in the handwriting of Charles II – “Pay this CR.” Under the King’s autograph appears a note in contemporary writing:- “This is his Maes. owne hand Robt Long.” On the reverse, above the receipt for 70 livres, is the date “12e Feb: 1649,” and below is the mark of Mary Grimsha. At the very bottom of the reverse, in the same hand and ink of Robert Long, as though intended for reference or “filing,” occur the words “Necessary Woman.” This note is within the age-soiled folds, forming a section of its own. Along the extreme edge of the left side of the reverse are written the words “The Necfsary woman – 70 1″: these are in the same hand and ink employed for the receipt.

It seems worth while to record this document because of the circumstances under which, as I believe, it was drawn up. The vendors described it as being one of the earliest documents signed by Charles II as King. But for several reasons this would appear not to be the case. According to contemporary English reckoning (Old. Style), when the year began on 25 March,12 Feb. 1649 would, of course, correspond to what we call12 Feb. 1650. In the February after the execution of Charles I (1648/9), however, his successor was living on the Continent as the guest of his brother-in-law and sister, William and Mary of Orange, at The Hague, where the year began on 1 January (new Style). Charles seems to have employed (sometimes O.S. and sometimes N.S. in the letters written by him from 1 Jan. to24 Mar. 1648/9. But that need not concern us here. The important point to notice is that the earliest date on which he could have signed his initia1s “C.R.” instead of “C.P.” is 2/12 February. At the end of A Declaration of the Cornish Men concerning the Prince of Wales (London, 1648/9, quoted by Ellis, Original Letters, 2nd series, III, 347) we read:- “Feb. 7. Letters from Southampton say that on Friday, Feb. 2d, the Prince received intelligence of his Father’s death.: (Some modern authorities give the date as 4/14 or 5/15 February). This fact alone seems to me conclusively to rule out the possibility of the Grimsha account, receipted as it is on 12 Feb. 1649, being dated according to N.S. But if further proof is needed, a little reflection shows how very unlikely it is that such an account should have been presented to Charles at The Hague. In the first place, it is highly improbable that he would have had to pay for the cleaning of his apartments in the palace. Nor was he in a position to do so. Clarendon, among other contemporary writers, testifies to the King’s complete destitution at this time. “He himself lived with and upon the Prince of Aurange, who supported him with all things necessary for his own person, for his mourning, and the like: but towards any other support for himself and his family, he had not enough to maintain them for one day” (History, Book XII, 3). William generously paid the royal servant;; out of his own exchequer, we learn from another source. In the second place, the account would certainly have been made out in guilders, not in livres. Among the Hodgkin MSS. (Hist. MSS. Commission. 15th Report, Appendix, II, 212 et seq.), there is an order signed by Charles, dated from The Hague, 6 June 1649, for a variety of disbursements, and these are in guilders.

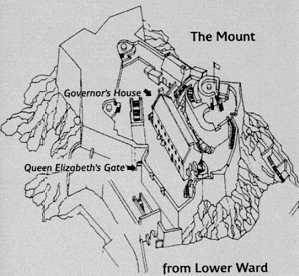

On 12 Feb. 1650, on the other hand, Charles II was residing in a place where O.S. was preserved in correspondence and legal documents, where the livre was in circulation, and where he was independent master of a household – namely the Island of Jersey. He and his brother; James, Duke of York, landed on the Island on 17 Sept. 1649 taking up their residence in Elizabeth Castle, where the King occupied the Governor’s House in the Upper Ward. Charles left Jersey on 13 Feb. 1650. “Ye space of 20 weeks” mentioned in the Grimsha document almost exactly corresponds with the Kings stay: it would cover the period from 17 Sept. 1649 to 4 Feb. 1650. And since it is to be supposed that Charles received accounts in anticipation of his departure, the bill would have been presented between that date and 12 February, the very eve of his embarkation, when, as it is pleasant to note, it was paid. All this, in my opinion, points to the conclusion that Mary Grimsha was Charles IIs “charwoman” at Elizabeth Castle from September 1649 to February 1650. That she had served him previously in a similar capacity the words “former allowance” would seem to indicate: possibly this was when he was inJersey as Prince from April to June 1646.

Nor is other evidence for my contention lacking. Mr. Charles suggests that part of the writing on the document is probably in the hand of Sir Edward Walker, Garter-King-of-Arms and Clerk of the Council, who was acting as receiver of the Kings money and making payments for him at least as early as June 1649, for it is to Walker that the above-mentioned order among the Hodgkin MSS. is addressed. In support of Mr. Charles’s surmise is the fact that he possesses a document dated “Constanne 24/14 ffe: 1649″ above the receipt for a payment of 600 livres to Major William Armorer, which is written in thc same hand and ink as the receipt and the words “The Neefary woman – 70 1″ on the Grimsha document, (Armorer was one of Charles’s equerries, who receives payment in the Hodgkin list). This second document is headed in the Kings autograph:- “Walkerpay to Armorer 600 livers Charles R.” It is therefore not unreasonable to suppose that both these documents are in Walker’s hand. in more favorable times it should not be difficult to establish this point. NowWalker

was with Charles inJersey. In the list of notable persons accompanying the King compiled by Jean Chevalier and incorporated in his invaluable Journal,Walker

figures under the curious disguise of , Sire Edouard vouasques.” As for “Robt Long,” he is indubitably, as Mr. Charles and I independently concluded, (Sir) Robert Long, who had been secretary to Charles as Prince, had had charge of his receipts and payments, and was sworn a member of the King’s Council shortly after his accession. Long, too, was in Jersey, acting as “principall secretary of state,” It is interesting to find among the Clarendon MSS. in the Bodleian Library a document (printed by Hoskins in his “Chales II in the Channel Islands, 350) dated “St. Hellaires in the Isle of Jersey the 29th of November 1649,” which bears the names of both Walker and Long.

But it is the Armorer document which, to my mind, clinches the matter. As has been seen, the same ink as well as hand occurs in both documents: therefore it is natural to conclude them to be closely related in time. The Grimsha account is dated 12 Feb. 1649 the Armorer 24/14 Feb. 1649. If the second document can be proved to be dated according to O.S., as far as the year is concerned, so surely must the first be: they will be separated by only two days. The first has no location; the second bears “Constanne.”. Now’ “Constanne” can be no other than Coutances in Normandy (the Roman constantia) where Charles II, on sailing from Jersey on 13 Feb. 1650, “lay that night and the following at the Bishops Pallace,” as we learn from the Journal of John Trethewy, secretary to Lord Hopton, who was with the Court in Jersey (Hoskins, op. cit., 378). The double date, 24/14 February, is employed because France has been reached, but, 1649, the O.S. year, has been kept. Can it, then, be doubted that, if the Grimsha document had borne a location, it would have been “St. Hellaires in the Isle of Jersey”?

It is the connection with Jersey, which I hope that I have succeeded in establishing, which gives the Grimsha document its interest and makes it, as I said, worth recording. For there is no episode in Charles II’s personal history more attractive than this second visit of his to the loyal Island. In 1854 Samuel Elliott Hoskin rendered a great service to historians by the publication of his Charles II in the Channel Islands.’ largely based on Chevalier’s Journal which he had diligently tracked down and transcribed An even greater debt is due to the Societe Jersiaise, which rendered accessible the complete text of the Journal (the MS. was then the property of Mlle Hemery, of St. Helier) by publishing it between 1906 and 1914. From the public point of view, those months in 1649 and 1650 were marked by important Scottish negotiations which may be studied in State Papers. From the private point of view, they were a happy interlude in the troubled lives of the two young Stuart princes, the story of which may be read in delightful detail in Chevalier’s seventeenth-century French. There is no doubt that, in spite of their deep mourning – Charles “estoit vestu dun habit viollet q est la coulleur q les rois porte,: while James was “reuestu tout en noir” – these boys of 19 and 16 thoroughly enjoyed their liberty in Jersey, where they shot, celebrated family birthdays with salutes of artillery, reviewed troops, and arranged “touchings” for the Kings Evil. The Mary Grimsha document provides a small but precious memento of this visit to Jersey of one who, in the words of Chevalier, “humble a toute personnes,” “bien accomply en tous ses membrs,” greatly endeared himself to the people of the Island,

Margaret R. Toynbee.

The payment of Mary Grimshas invoice was apparently the exception rather than the rule – the destitute King was in the habit of leaving most of his debts unpaid.

Marjorie Grimshaw’s Research into Mary Grimsha

Marjorie has conducted considerable research into Mary Grimshaw and has prepared the following article (April 2004) for the magazine of The Channel Islands Family History Society:

My interest in Mary Grimsha started some years ago when I read in the Jersey Evening Post an article regarding the sale at Sotheby’s of a document signed by Charles II which authorised a payment to his charwoman Mary Grimsha. The document was very interesting because Charles II was penniless when he was in the Island and left debts unpaid; his living costs and those of his courtiers were paid by Sir George de Carteret. It was therefore amazing that Charles II should wish to pay Mary for her services. Below the King’s request “pay this/CR” is a note written by Sir Robert Long stating “necessary woman” On the reverse of the document is a receipt dated February 12, 1649 signed by Mary Grimsha with her mark. The original document is now owned by The States of Jersey and is held at the Jersey Archive. As very few records were kept at that time, the only verifiable document is the bill/receipt and an article written in June 1944 by Mrs. Margaret Toynbe in which she states that it is one of the earliest documents signed by Charles II as King.

After seeing and obtaining photocopies of the bill/receipt and a copy of the article written by Mrs. Toynbe, I suspected that Mary must have come to the Island as one of the passengers in the “Proud Black Eagle” or in one of the two accompanying ships as they brought in “chief officers of the household with their wives, families and servants as well as all sorts of artificers, craftsmen and lesser servants” (Major Rybot’s booklet Elizabeth Castle). However I have found no evidence that she arrived in the Island at this time, although she was in Charles II employ for both his visits.

Just recently, I heard of a story which purported that Mary Grimsha had a cottage at Bel Royal, St. Lawrence and that Charles II ‘visited’ her there. My difficulty now is to trace the cottage and find out whether the Grimshaws owned or lived in the cottage prior to Charles II (then Prince of Wales) visits to the Island, or whether it was bought for her use by one of his courtiers. If the latter was the case then it might be possible to trace the purchase through the Land Registers. At every turn one is thwarted by lack of evidence to either prove or disprove my theories and every thing is a matter of speculation. Whether I will ever be able to trace any of Mary’s life is questionable.

The Grimshaw name goes back to Viking times, but the first written evidence of the family comes in 1250 AD. Walter Grimshaw and his family are closely associated with the Grimshaw location in Eccleshill but it is thought that the family had already been in existence for over 200 years… Walter was the progenitor of most, if not all, Grimshaw lines that have survived into present times. It is thought that 35/40 lines have spun out from Walter Grimshaw’s line (most of the research and hard work on the Grimshaw family has been carried out by Tom Grimshaw with help by other Grimshaw historians – web site http://www.grimshaworigin.org) My research has been to try and place Mary Grimsha into one of these family lines but this is proving very difficult as without any indication of age is an almost impossible task. However if Mary Grimsha and her family lived in the Island prior to 1648 then maybe I will be able to add to Walter Grimshaw family with a Jersey line descending directly from him!!!

Marjorie Grimshaw Member No 1085

After preparing the article, Marjorie determined that the cottage at Bel Royal is now known as is called “Maison Charles”.

Why Was the King of England Staying on the Small Island of Jersey?

Charles II (Figure 3) stayed on the island of Jersey on two occasions – the first in 1646, when he was still a prince, and the second in 1649-50, as King of England.

Figure 3. Portrait of Charles II. (Source: www.britannia.com/history/monarchs/mon49.html )

The reasons for Charles IIs visits are best understood in the context of a brief biography; the following is from Encyclopedia Britannica Online::

Charles II

born May 29, 1630, London

died Feb. 6, 1685, LondonThe Merry Monarch king of Great Britain and Ireland (1660-85), who was restored to the throne after years of exile during thePuritanCommonwealth. The years of his reign are known in English history as the Restoration period. His political adaptability and his knowledge of men enabled him to steer his country through the convolutions of the struggle between Anglicans, Catholics, and dissenters that marked much of his reign.

Birth and early years

Charles II, the eldest surviving son of Charles I and Henrietta Maria of France, was born at St. James’s Palace, London. His early years were unremarkable, but before he was 20 his conventional education had been completely overshadowed by the harsh lessons of defeat in the Civil War against the Puritans and subsequent isolation and poverty. Thus Charles emerged into precocious maturity, cynical, self-indulgent, skilled in the sort of moral evasions that make life comfortable even in adversity.

But though the early years of tawdry dissipation have tarnished the romance of his adventures, not all his actions were discreditable. He tried to fight his father’s battles in the west of England in 1645; he resisted the attempts of his mother and his sister Henrietta Anne to convert him to Catholicism and remained openly loyal to his Protestant faith. In 1648 he made strenuous efforts to save his father; and when, after Charles I’s execution in 1649, he was proclaimed Charles II by the Scots in defiance of the English republic, he was prepared to go to Scotland and swallow the stringently anti-Catholic and anti-Anglican Presbyterian Covenant as the price for alliance. But the sacrifice of friends and principles was futile and left him deeply embittered. The Scottish army was routed by the English under Oliver Cromwell at Dunbar in September 1650, and in 1651 Charles’s invasion ofEnglandended in defeat at Worcester. The young king became a fugitive, hunted throughEngland for 40 days but protected by a handful of his loyal subjects until he escaped toFrance in October 1651.

His safety was comfortless, however. He was destitute and friendless, unable to bring pressure against an increasingly powerful England. France and the Dutch United Provinces were closed to him by Cromwell’s diplomacy and he turned to Spain, with whom he concluded a treaty in April 1656. He persuaded his brother James to relinquish his command in the French army and gave him some regiments of Anglo-Irish troops in Spanish service, but poverty doomed this nucleus of a royalist army to impotence. European princes took little interest in Charles and his cause, and his proffers of marriage were declined. Even Cromwell’s death did little to improve his prospects. But George Monck, one of Cromwell’s leading generals, realized that under Cromwell’s successors the country was in danger of being torn apart and with his formidable army created the situation favourable to Charles’s restoration in 1660.

Most Englishmen now favoured a return to a stable and legitimate monarchy, and, although more was known of Charles II’s vices than his virtues, he had, under the steadying influence of Edward Hyde, his chief adviser, avoided any damaging compromise of his religion or constitutional principles. With Hyde’s help, Charles issued in April 1660 his Declaration of Breda, expressing his personal desire for a general amnesty, liberty of conscience, an equitable settlement of land disputes, and full payment of arrears to the army. The actual terms were to be left to a free parliament, and on this provisional basis Charles was proclaimed king in May 1660. Landing at Dover on May 25, he reached a rejoicingLondon on his 30th birthday.

Restoration settlement

The unconditional nature of the settlement that took shape between 1660 and 1662 owed little to Charles’s intervention and must have exceeded his expectations. He was bound by the concessions made by his father in 1640 and 1641, but the Parliament elected in 1661 was determined on an uncompromising Anglican and royalist settlement. The Militia Act of 1661 gave Charles unprecedented authority to maintain a standing army, and the Corporation Act of 1661 allowed him to purge the boroughs of dissident officials. Other legislation placed strict limits on the press and on public assembly, and the 1662 Act of Uniformity created controls of education. An exclusive body of Anglican clergy and a well-armed landed gentry were the principal beneficiaries of Charles II’s restoration.

But within this narrow structure of upper-class loyalism there were irksome limitations on Charles’s independence. His efforts to extend religious toleration to his Nonconformist and Roman Catholic subjects were sharply rebuffed in 1663, and throughout his reign the House of Commons was to thwart the more generous impulses of his religious policy. A more pervasive and damaging limitation was on his financial independence. Although the Parliament voted the king an estimated annual income of £1,200,000, Charles had to wait many years before his revenues produced such a sum, and by then the damage of debt and discredit was irreparable. Charles was incapable of thrift; he found it painful to refuse petitioners. With the expensive disasters of the Anglo-Dutch War of 1665-67 the reputation of the restored king sank to its lowest level. His vigorous attempts to saveLondon during the Great Fire of September 1666 could not make up for the negligence and maladministration that led toEngland’s naval defeat in June 1667.

Source: “Charles II” Encyclopædia Britannica. <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article?eu=22917>, [Accessed January 4, 2003].

Both of Charles IIs visits to Jersey were thus occasioned by the English civil war and the temporary loss of power of the English monarchy when Charles IIs father was executed by beheading in 1649.

Description of Charles II’s Visits to Jersey

Rybots history of Elizabeth Castle2, where Charles stayed during both visits, includes an excellent description of the two visits:

THE FIRST ROYAL VISIT

The period 1643-1651, as I have attempted to show, teems with events which, albeit of a local character, are not devoid of interest. I shall now outline a few incidents of two others of wider appeal, namely, the visits of refugee royalties and great noblemen.

While Charles I was preparing for the campaign which ended disastrously at Naseby, Prince Charles, then only fifteen, had been given nominal command of the Royal forces in the south-west ofEngland. Beaten back into Cornwall and threatened with capture, the Prince with his Council and suite took ship for the Isles of Scilly; but, finding them untenable, re-embarked on 16th April 1646 in the Proud Black Eagle and two other vessels, and sailed across Channel to Jersey, where they dropped anchor off Elizabeth Castle the following evening.

No salute welcomed the Prince nor was any demonstration made as he entered the Castle. Orders were issued the same night that no private boats were to leave the island for three days, so that the secrecy of the arrival might be preserved. The Proud Black Eagle must have been a crowded little ship, for besides the Prince she bore a number of lords, knights, gentlemen and divines whose style and titles Jean Chevalier sets down with the utmost gusto. The other ships, though smaller, carried a still larger number of passengers, as they brought the chief officers of the household with their wives, families and servants as well as all sorts of artificers, craftsmen and lesser servants.

The total number of the suite is given as three hundred persons, and from the description of their offices and duties, one gathers that a brave attempt was made to maintain within the rough walls of Elizabeth Castle the ceremonious formalities and atmosphere of a royal palace.

On the day after the Prince landed, Lord Wentworth was sent to France to carry the news to Queen Henrietta Maria, who was then at Saint Germain. On the same day commenced the difficult task of finding suitable accommodation in Castle and Town for this influx of distinguished visitors.

The Governor’s House in the Upper Ward was assigned to the Prince and quarters were found in both Wards for his chief officers and their staffs. A number of the nobility and lesser fry found lodgings in the Town, some hiring entire houses, others being content with a mere bedroom. The presence in their midst of the heir to the tl1rone at once aroused the entl1usiasm of tl1e islanders. Without loss of time all the best people hurried out to the Castle to kneel before the Prince and kiss the royal hand.

Meanwhile the feeding of all these grandees was occupying the attention of the local authorities and their decisions on the matter were proclaimed throughout thy island. Two parishes at a time daily were to provide meat for the Prince and deliver it at the Castle. For the rest of the refugees meat was to be brought into the Market Place every Wednesday and sold at fixed rates. Thus mutton was to cost three soils a pound, lamb three and a quarter sous, veal two and a quarter soils and beef two and a quarter soils. For poultry no price was fixed. Its cost depended upon the bargaining powers of the purchaser.

To ensure a good supply of fish, the fishermen had orders to bring in bass, mullet, turbot, soles, mackerel and lobsters, and if they failed so to do, were to suffer such corporal punishment as it might please Sir George to award. Over and above all this, no one in the island might buy anything until it was known that the wants of the visitors had been satisfied. As soon as the news of this business revival reached the Norman coast, the local market became stocked with imported sheep, chickens, capons and geese and thus all fears of a famine were averted.

On Sunday, 19th April, the inhabitants of every parish expressed their feelings of loyalty by firing jeux-de-joie and lighting bonfires just before sundown.

One week later the Prince went ashore for the first time to attend divine service in the parishchurch of Saint Helier. As befitted the unsettled state of the times, the procession which issued from the Castle that day was martial in character. At its head about a hundred cavaliers pranced and clattered over the Bridge and behind them followed three hundred matchlock men with their drums and ensigns. Last come the Prince himself with his nobles and gentlemen.

Such a sight as this had never before gladdened the eyes of the people of Jersey and it is no wonder that the sands were covered with “a countless number of common people” who had flocked in from all the parishes and trouped out right up to the gates of the Castle. In this multitude women and girls, as was natural, predominated. This crowd accompanied the procession into the streets of the town which were already almost impassable with other excited hordes. Through the augmented press a lane was driven with difficulty and down it the Prince’s party managed slowly to force its way.

In the neighbourhood of the Church the enthusiasm reached its climax. Here, however, the musketeers established a strong cordon all round the walls of the cemetery and placed guards over the doors so that the Prince and his suite were able to enter the building without further trouble. Without these precautions the church would have been filled to overflowing with persons who would not have understood one word of the service, for it was conducted in English by a royal chaplain.

Straight in front of the minister’s pulpit, a chair and a table had been placed for the Prince, and the floor round about covered with carpets and sweet smelling flowers. On the table was a cover and on the cover beside a cushion for the royal elbows, roses were scattered. Beneath the table was another cushion for the royal knees. Seats were provided for the great nobles behind the Princes’s chair, but the lesser nobles and persons of quality had to stand throughout the service. Chevalier notes that everyone, including the Prince, remained uncovered as long as they were in the church. During the service Doctor Poley stood at the Prince’s side and held the book for him, turning the pages as required or pointing out the passages to which the preacher referred in his discourse.

Having given this sample of the sufferings of royalty when it goes to church, let me now describe the sufferings it endures when it has its dinner. The room in which the Prince dined was presumably on the ground floor of the Governor’s House in the Upper Ward, a low and not too well lit apartment. A number of lords, knights and gentlemen stand uncovered at the far end of the room. The Prince enters with his hat on and is at once approached by an esquire, who kneeling on one knee, proffers him an ewer resting on a dish, both of silver gilt. After rinsing his hands the Prince stands uncovered at the head of the table while a Doctor of Divinity recites a short prayer. He then replaces his hat and takes his seat. In front of him is a silver plate, a knife and a silver fork, the rest of the table being covered with an assortment of viands in silver dishes resting on silver platters. At the lower end of the table is an esquire in charge of the carving whose duty it is to cut the meat and taste it before lifting the portion with a silver fork and placing it upon a silver plate which is then set in front of His Highness. If the Prince is in good appetite, all the dishes are presented, one by one, and those for which he expresses a fancy are dealt with, as already described, by the Gentleman Carver. His bread, meanwhile, has been cut into long morsels and set by his side on yet another silver plate.

Can he relieve the tedium of all this stately ceremonial by seizing a tankard and draining it at a gulp? No, dear reader, he cannot. If he wishes to drink he must make some dignified sign, when an esquire of about his own age will advance to the gentleman Butler with a silver cup. When the cup is full the esquire tastes of its contents and then on banded knee offers it to the Prince. At last a drink. And what a drink. Barely has the cup reached the lip when the same esquire holds a second cup under the Prince’s chin, thus preserving his raiment from chance soilure. Should a second drink be required, a low obeisance is made and the cup taken back to the Gentleman Butler. “If after this, the Prince has any appetite left, ” says Chevalier naively, “the meal is continued. ” When dessert is finished, an esquire removes the breadcrumbs on a silver dish, and the Prince rises. The Doctor of Divinity mutters another prayer and the dinner is over.

Of all the ceremonies that Charles had to endure while cooped up in Elizabeth Castle with a crowd of elderly and disheartened men, royal reviews probably gave him the least annoyance. On 29th April a levee en masse was raised for his edification. Early that morning he had ridden off with a swarm of cavaliers to see Gorey Castle and to dine there with its commander, Philip de Carteret, Sir George’s younger brother, and on his return he found the whole armed force of the island awaiting his inspection on the sands in Saint Aubin’s Bay. The troops were massed in three columns under Colonels Philip de Carteret of Saint Ouen, Amice de Carteret of Trinity and Jean Dumaresq of Saint Helier. All the parish guns were on parade and around and about was everyone else in such profusion that at least two-thirds of the population of the island must have been present. Loud and prolonged shouts of “Dieu sauve le Roi et le Prince” greeted him, and delighted with the genuine warmth of his reception, he raised his hat repeatedly as he rode down the ranks.

When the Prince arrived at the head of the right column, Colonel Philip de Carteret approached him and knelt upon one knee. “What is your name, ” asked the Prince, alighting from his horse. “Philip de Carteret, Sire, ” replied the Colonel. The Prince then took de Carteret’s sword and waving it gracefully over the head of the kneeling man, touched him on either shoulder and said “Sir Philip dc Carteret, rise up. ” After this pleasing episode was over, the Prince withdrew to a discreet distance and the troops fired three volleys. Salutes from the guns followed and then all the officers came to the front and were presented individually.

The Prince commanded a large sum of money to be distributed among the officers and men as a mark of his appreciation of their loyalty and good service and the review closed with a final discharge of volleys. Alas that such a day should have such an ending. The men, writes Chevalier, were by no means edified at the manner in which the Prince’s largesse was distributed. Everyone must have calculated to a nicety what he should have received and the calculation in no wise tallied with what he did receive. Hence the tears.

I must now omit a number of interesting incidents chronicled by Chevalier and say au revoir to the Prince.

On 30th June six lords with a train of about eighty lesser persons arrived from France with orders from the Queen to bring the Prince to Paris. To the Prince, poor fellow, this was welcome news, as it also was to a number of the other refugees. But to many members of the Council it was otherwise. They very rightly argued that as long as the Prince was in Jersey he was on English soil. His flight to a foreign country would be interpreted as an acknowledgement of defeat. Long and bitter were the arguments between the opposing factions, but the orders of the Queen and the wishes of the Prince proved decisive. On 23rd June all was ready for the start and five or six vessels with the baggage were actually under weigh, when two Parliamentary warships appeared. The baggage vessels were recalled and the departure postponed. It was not till the evening of the 25th after two more attempts to get away had been frustrated, that the Prince, having taken leave of the die-hards who refused to go with him into exile, took his place in the pinnace for transference to his ship. He reached Coutainville on the opposite coast at eleven that night.

THE SECOND ROYAL VISIT

At 4 p.m. on Monday, 17th September 1649, King Charles II, aged 19, and his brother James, Duke of York, aged 15, arrived in Jersey and took up their residence in Elizabeth, Castle, the King occupying the Governors House in the Upper Ward and the Duke the house built for Sir Edward Hyde at the west end of the Priory Church. The day previous they had been the guests of the Bishop of Coutances, in whose diocese, as we have seen, the Channel Islands formerly had been included.

Three small frigates and about eighteen boats were awaiting the royal party at Coutainville, but as the weather was fine and the wind fair, the King refused to board a frigate and decided to make the crossing in the small galley or pinnace which had been built for him when he was last in Jersey. This boat was propelled by eighteen oars and in it the King, the Duke, Lord Brentford, Lord Hopton and a few others embarked, while the frigates, acting as convoy, gave passage to the other distinguished personages. The firing of guns from the ships and the Castle, together with volleys of musketry from the garrison, greeted the King as he came ashore, as did also Sir Philip de Carteret, Seigneur of Saint Olien, who, to accomplish his seigneurial duty, rode up to his horse’s girth in the sea and bowed three times.

On the following day the boats came in with a number of the lesser folk and a quantity of the baggage, after which they returned to Colitainville for the rest of the impedimenta.

The twinkling of the beacon fires which illumined the uplands of Jersey and the faint reverberations of royal salutes did not fail to attract the attention and arouse the curiosity of the Parliamentary commander in Guernsey and he despatched two warships and four frigates the next morning to report on the cause 01- this unusual demonstration. These vessels were afraid to draw within range of the Castle artillery; but their captains were well aware that not only was their mere presence an insult which the King would have to swallow unavenged, but was also a threat to his hold on Jersey, the last remaining fragment of his kingdom.

It was fortunate for the King that his baggage boats and their escort were of light draught, for by hugging the coast-line they passed in, just out of range of the enemy guns.

Charles being now King, lived in greater state than of yore. There came with him from France a following of some three hundred people whose numbers at times, owing to the frequent arrivals of persons connected with affairs of state, rose to a much higher figure. Among the actual members of the court were two dukes, two earls, six lords, fourteen knights, twenty-four gentlemen (secretaries, pages, grooms of the bedchamber, ushers, etc.), four doctors of divinity, two physicians, one apothecary, nine colonels, two captains, two butlers and two tailors.

Three coaches upholstered in black came with the King as well as a number of covered wagons for his most valuable clothing and effects. Each coach had its complement of six black horses, for the court was in mourning. Black was the clothing of everyone. Only the King wore purple, for that is the sovereign’s mourning colour. The total number of horses was one hundred and twenty, “great and powerful animals” tended and exercised by a crowd of grooms and ostlers.

The experience gained during the first royal visit simplified for Sir George Carteret the problem of housing and catering for this second influx. By reviving the old marketing regulations and encouraging imports from Normandy, supplies for man and beast were soon forthcoming in sufficient quantity and at reasonable rates and thus in spite of the crowded state of Castle and Town, the Court settled down as comfortably as the uncertain state of affairs permitted.

Receptions, royal birthdays, reviews, oath-takings, inspections, church parades, excursions by land and sea and the arrivals and departures of ships of the piratical ‘Royal Navy’ filled the days with movement and excitement. The detonations of fire-arms, large and small, punctuated every occasion. In fact the amount of powder burnt at peaceful rejoicings far exceeded the amount expended in warlike operations.

Though it is not possible to set down here many of the incidents described by Chevalier during the King’s visit, a few have been selected for their illustrative value. They include ~ duel, a review, a state function, a Punishment, and a church service.

A DUEL -Bickering, back-biting and scandal-mongering are the natural and unfortunate concomitants of the overcrowded and penurious conditions to which the courts of refugee princes are ever subject. The limitations of life in Elizabeth Castle must have set everyone’s nerves on edge. It does not surprise one, therefore, to read that two captains of the King’s company stepped out onto the sands one morning to settle their differences with the sword. No seconds attended the encounter and thus after one of the combatants had been brought in mortally wounded, the statement of the other had to be accepted as evidence by the court which trie1l him. This statement, which was supported by the dying declaration of the victim, maintained that the wound was accidental, in that it was caused by the man falling on his own sword.

Thus the survivor escaped with his life and received the King’s pardon, but to prevent the recurrence of such a tragedy, a royal proclamation was published in the Market Place forbidding any Englishman attached to the court to challenge or accept a challenge to a duel on pain of dismissal from his office and banishment from the country. If in defiance of this warning a duel were fought, the survivor or survivors would be punished with death.

A REVIEW- The review held on the sands about one mile north-west of the Castle on 31st October 1649 must have been the largest concentration of armed men ever assembled in Jersey prior to the Napoleonic wars.

The Castle garrison was there, the Lieutenant-Governor’s company, the Dragoons and Light Horse, the Parish Artillery with their field guns and tumbrils and the insular Infantry, in all some two thousand seven hundred men. The infantry was drawn up in six ranks in open order, a normal formation for the musketeers of the period. The centre of the line was occupied by the pike-men. The object of the six-rank formation was to ensure a continuous fire. Thus as soon as the front rank had discharged its matchlocks it would at once retire through the intervals in the ranks behind, and then reform and reload. It thus became the sixth rank. Meanwhile the second rank had become the first rank and was discharging its matchlocks. This manoeuvre brought all the ranks to the front in rotation, but unless it were performed by troops drilled into machine-like precision it must have led to indescribable confusion even on the parade ground. The loose formation of the musketeers and the continuous interior movements made these bodies particularly vulnerable to cavalry attack. Hence a stout body of men armed with long pikes was provided as support. The invention of the bayonet many years later turned the musketeer into a musketeer-pikeman. Elasticity of manoeuvre and an increased volume of fire were gained by the adoption of this simple expedient.

The King and the Duke of York rode out of the Castle accompanied by their lords, knights and gentlemen and went down the line at a walking pace, the men “standing firm in their postures,” raised their hats on high shouting “Vivre le Roi,” “Dieu sauve le Roi” or “Dieu vous remettre sur votre trone.” When the royal party came to the end of the line, the troops were turned about and the King completed the circuit of the force, finally taking up his position on the left flank when the firing of volleys and gunfire salutes commenced. When this ceremony was finished the artillery gave a display with shotted guns, firing over the sands toward the sea, where the balls bounded and ricocheted amid the applause of the delighted assemblage.

Meanwhile the King was becoming a focus round which the women, girls and children were concentrating regardless of the restiveness of his charger. “With his own mouth he warned them to be careful” fearing that some of them would be injured. “Nevertheless the people were so excited at his presence that they tried to place their hands upon him or touch him if they could. “

The captains and company commanders now came forward to kiss the King’s hand and this, followed by another volley and the approach of twilight, brought the review to a close. To the troops who had been on their feet for the greater part of the day and now had to trudge off homewards, the order to dismiss must have been very welcome. In fact there was probably only one man present who had not had enough for the day and that of course was the indefatigable Sir George. He, it seems, had set his heart on terminating this ‘record’ concentration with a ‘record’ oath-taking. This time, however, his will was thwarted and the oath had to be administered later in a humdrum manner, parish by parish.

A STATE FUNCTION -The selection made under this heading is of a peculiar character in that it deals with certain miraculous powers of healing with which monarchs were supposed to be endowed.

These powers were of particular efficacy against scrofula, for which reason the disease was popularly called ‘The King’s Evil.

On 8th December 1649 eleven persons, said to be suffering from scrofula, were examined by the King’s Physician, who satisfied himself as to their condition.

It was customary on these ‘touching’ occasions for the King” at the end of the ceremony, to suspend a gold coin on a ribbon round the neck of the sufferer; but the Physician reluctantly had to point out that the King had now no gold coins in his possession. Each patient, therefore, was asked to supply his own coin and white silk ribbon and place them in the keeping of the Physician until they should receive them back again from the King.

On Tuesday, 11th December, out came the eleven to the Castle. The King and the Duke were seated awaiting them in the choir of the Chapel, while at hand stood a Minister and the Physician with the be-ribboned coins

The eleven were placed on the opposite side of the choir and one by one were led up to the King and told to kneel before him; whereon the King placed his hand on the sufferer and said “May God heal you”; after which the Minister said a short prayer. When all had been ‘touched’ they again knelt in turn before the King who placed round the neck of each his own coin. This was Charles’ first ‘touching’. In January and February of the following year he treated nine or ten more cases in the same manner.

A PUNISHMENT- Though the soldiers most prone by nature and up-bringing to the commission of crime were the Irish, Sir George had made an attempt in 1647 to improve their moral tone by selecting three of the most agile to serve him and Lady Carteret as running-footmen or peons, clothing them in his livery of red and white. For several months all went well. Unfortunately on the night of 3rd October 1647 Sir George took it upon himself to see if the sentries were alert and the guards present and correct. Suddenly through the gloom he saw a strange sight. The guard were hauling the body of a sheep over the battlements, while at the foot of the wall outside was another group of men and some more suspicious bundles. Himself unobserved, Sir George said nothing and returned to bed; but the next day he descended unannounced on the thieves’ kitchen and found a cauldron full of mutton and cabbages on the boil and a quantity of flesh, fruit and fowl strewn round about in Irish disorder. All these good things at once were confiscated and distributed amongst the other troops, while the culprits were strapped to the horse for various periods of torture.

When the King was in the Castle another Irishman -we will assume it was not one of the first lot -was convicted of stealing a turkey-cock and he also was subjected to the punishment of the horse, an animal, by the way, which was made of wood after the fashion of the vaulting-horse still used in gymnasia. By means of straps, tightly applied, the rider was kept upright and the strain on his legs was increased to torture point by the attachment of weighty objects to his feet. The turkey stealer suffered an additional indignity by having his victim’s wings tied to his head, crest-wise.

A CHURCH SERVICE -The service about to receive notice is included for the sake of an incident which enlivened it.

Among the people who followed the Court to Jersey was a curious little Frenchman named Jean de Lancre, a native of Saumur. He was proficient in Greek, Latin and English and had written books in these languages as well as in his own. His lively conversation and sallies or wit afforded the King much entertainment and earned him his clothing, board and lodging. His grotesque gestures and monkeylike antics, however, indicated that the poor little fellow was mentally unbalanced.

On Sunday 25th November 1649 Saint Helier’s Church was furnished with chairs, cushions, carpets and tables for the attendance of the King and Duke in state. Some time before the Court was due, the dwarf entered and sat himself down before the pulpit grimacing and clapping his hands. He even attempted a harangue at the top of his voice, harmless in itself, but to the Church officials unacceptable as a hors d’oeuvre. They, therefore, threw him out and kept him out. Then the King and his Court arrived amid the usual demonstrations on the part of the excited crowds, and the service commenced.

The angry little Frenchman now tried to pass the guard and force his way back into the Church; but being roughly repulsed, he fell into a tremendous rage and rushed round to the back of the Church where he armed himself with three large stones. The first of these he discharged straightway through the nearest window. The second crashed through a window further to the east and missed the King’s head by a hair’s breadth and the third smashed in elsewhere. The shattering of the glass and the downfall of the stones among the packed congregation must have created a first class sensation. The King, recognising the yells of the little man, began to laugh, while poor Sir George, purple in the face, rushed out of the Church in pursuit of the madman, and having caught him sent him off a prisoner to the Castle. The next day he was led away to durance il, Mont Orgueil. At the end of a couple of weeks he escaped and reappeared in Elizabeth Castle where he sought audience with the King. Here, one is glad to learn, the King pardoned him, and having fitted him out with a new suit of black clothes and filled his purse with silver, caused him to be repatriated. At the time of the King’s arrival in Jersey it was proposed that he should proceed to Ireland and assume command of the forces there; but before any decision had been taken in the matter, news came that Cromwell had invaded Ireland and dealt with the situation in his most drastic manner. Confirmation of the disaster was brought early in January 1650 when a frigate arrived from Waterford with despatches as well as a large number of refugees, who were for the most part ladies of quality.

Other and more promising plans for the reconquest of England had also been the subject of negotiation in Elizabeth Castle between the Court and Presbyterian emissaries from Scotland, and it was decided to follow these up with an assemblage of plenipotentiaries at Breda in Holland. The Scotch commissioner and his colleagues left Jersey on 13th January to confer with their government. On the 18th, the Duke of Buckingham and sundry lesser personages came over from France bearing messages from Queen Henrietta Maria urging the King to hasten to Holland and press on with the Scotch negotiations.

The Duke of Buckingham remained in the Castle till 21ld February when he sailed to Coutainville to rejoin the Queen and assure her that the King would meet her shortly ill Rouen and discuss the situation before he went On to Holland. With him set out a number of Charles’ officers and servants, whose duty it was to make advance arrangements for the King’s journey through Normandy and to assist Lord Percy and others who had already departed on that errand. The movement of baggage and followers continued unremittingly, for the ships were small and the amount of stuff to be shifted large. Horses, coaches, wagons, equipage, stores and a thousand and one personal properties had all to be loaded up and transported across the narrow seas. Chevalier reckoned that at least five hundred men and women had to be provided with passages. During all these days Elizabeth Castle must have been ill a turmoil. The boats and little ships left stranded On the Bridge or in the harbour of Saint James were loaded from Town and Castle when the tide was out, rough country carts and pack animals conveying the baggage from the Town and soldiers and men servants staggering out with bundles and packages from the Castles.

No untoward event appears to have interfered with this migration. Not only must the weather have been favourable, but the earliness of the season evidently found the enemy flotilla in Guernsey unprepared for action.

On Wednesday, 13th February 1650, between nine and ten in the morning, Charles departed on that great adventure which was to end so dismally in the rout of Worcester. The Duke of York and Sir George Carteret saw him aboard Captain Amy’s frigate and there bade him adieu. No parting salutes were fired from ship, castle or shore, for officially the departure was secret. Actually the departure was known throughout the island, having been a subject of gossip for the previous two weeks.

With the passing of all this great and brilliant throng, Elizabeth Castle would have reverted to its former comparative unimportance had it not been for the presence of the Duke of York, whose continued residence there saved it from political oblivion. This lad of fifteen, when his brother had gone, moved up into the Governor’s House and lived there engirt by the same stiff formalities of courtly procedure which had surrounded his brother the King. His staff included various gentlemen of the bedchamber, a secretary; a treasurer, the officers who functioned at the dinner table, six pages, a valet, a tailor, two Doctors of Divinity, a Master of the Horse, six peons and sundry servants and grooms.

The Duke, besides being an excellent horseman was a first class shot, and Chevalier notes with admiration that he killed his partridges on the wing, preferring to bag the birds himself rather than to fly his hawks at them. Shooting was his chief delight and his sporting excursions took the form of picnics, although the etiquette of the Court demanded even then that his companions remained uncovered in his presence. He avoided the town more than the King had and whenever he could he exchanged the publicity of the Castle for the privacy of the lanes and fields, sometimes crossing the Bridge at dawn, carrying his breakfast with him. On these occasions the country gentlemen hastened to offer him their hospitality, but he invariably refused to enter their homes, preferring to sit under a tree and cat his food untrammelled by the ceremonies that governed his meals in the Castle. His gentlemen, however, were more sociable, and often accepted the invitations which the Duke had refused, thereby pleasing their hosts almost as much as if the Duke himself had honoured them.

His Doctors of Divinity he could not dodge, and consequently had to endure as best he could the daily service in the Chapel and the sermon which followed it.

Altogether the Duke of York stayed eleven months and one day in the Castle, that is to say six months and six days after the King had departed. During that period he acted as Governor of Jersey with the energetic Sir George Carteret as his Lieutenant. Ships kept on coming with refugees and despatches and Sir George kept on trying to perfect the military machine he had evolved with such trouble. Supply boats for the beleaguered Castle Cornet were despatched periodically and the activities of the royal piratical flotilla continued unabated. Birthdays and anniversaries as of yore, were celebrated with cannon and musketry fire and the copious drinking of loyal toasts.

On 12th May 1650 Sir Richard Lane, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, died in the Castle. Illness had prevented this distinguished man from accompanying the King to Holland. Chevalier gives a full description of his funeral and remarks that Lane was the first lord to be buried in Saint Helier’s Church. The Duke accompanied the procession as far as the north end of The Islet. Its advance guard consisted of eighty matchlockmen with arms reversed, and three drummers with their drums draped in black. Four men carried the coffin and eight gentlemen of the Household acted as pall bearers, Sir George amongst them. The pall bore the arms of the deceased on its ends and sides. The arms were painted on paper and are described by Chevalier as a lion between three crosses. Three volleys of musketry were fired as the coffin was lowered and a salute of seven guns was discharged from the Castle. The last of the seven was unfortunately shotted. The ball whizzed over the Cemetery and fell outside the eastern limit of the town at the door of the house of one Philip Pallot just as Madame Pallot was coming out. The woman sprang back unhurt and the ball ricochetted over a wall into the garden, where it damaged a pear tree and then buried itself eighteen inches in a ditch.

About a week after Sir Richard Lane’s funeral six sailors arrived from England with a tale of woe. The ship which Sir George had fitted out for the colonisation of New Jersey had been captured, within two days of its departure, by a Parliamentary frigate of twenty guns and taken into Falmouth, where these six men who formed part of the captured crew, had been released.

The story connected with the ship commences shortly before the King left Jersey, when His Majesty “gave Sir George Carteret, Lieutenant-Governor of Prince James, Duke of York, an island near Virginia in America, which was inhabited, and other islands thereby. These, the King gave Sir George for himself and his heirs, with permission to build a church and a castle and establish such laws and customs as he might find agreeable and expedient for the country and island. Further, he was empowered to raise a body of three hundred souls to colonise the place and grow sugar, cotton, tobacco and such other produce as might grow there. This territory was called New Jersey in the Patent, which was duly signed and sealed by the King.” The original name by which the island was known was Smith’s Island, and it was the King himself who rechristened it.

During the ensuing two months an expedition was prepared to give effect to the terms of the Patent and a ship was fitted out with the utmost care and forethought. In charge of the twenty-five or thirty Jersey emigrants who accepted land in the New World, under varying terms of tenure, was Philip de Soulement, an Advocate of the Royal Court, who was accompanied by two or three of his own men.

Perhaps the most valuable recruit was a Thomas Le Vesconte who came over from England to join the party. This man already possessed a plantation in Virginia and thus was able to give Sir George all sorts of valuable information and advice. A third important participator in the adventure was William Davenant who, though a poet and a dramatist, possessed the spirit of a man of action. His following included fifteen emigrants of the right sort, all masters of various useful crafts. * Apart from these were two passengers for whom Chevalier expresses no admiration, namely the Capuchin monks Savigny and du Plessis. These two had been attached to the Court of the Queen Mother and had made that august lady ill by compelling her to walk about at night with bare feet as a penance. Their mission was of a twofold nature. First they were to act as chaplains to Davenant’s people on the voyage, and later to act as missionaries to the Red Indians as well as to keep an eye on the doings of the Puritan Governor of the colony. The ship, a prize taken piratically from the Danes in 1649, left the anchorage of Elizabeth Castle on 3rd May 1650 a Friday. The superstitious might have predicted its fate.

The Duke of York left Jersey on 21st August 1650 under a parting salute of nine guns. His funds were so low that before leaving he dismissed from his service his cup-bearer, two grooms of the chamber, his gentleman butler, two peons and various other lesser persons, promising them re-employment when he came into his own again.

Jersey and Elizabeth Castle History

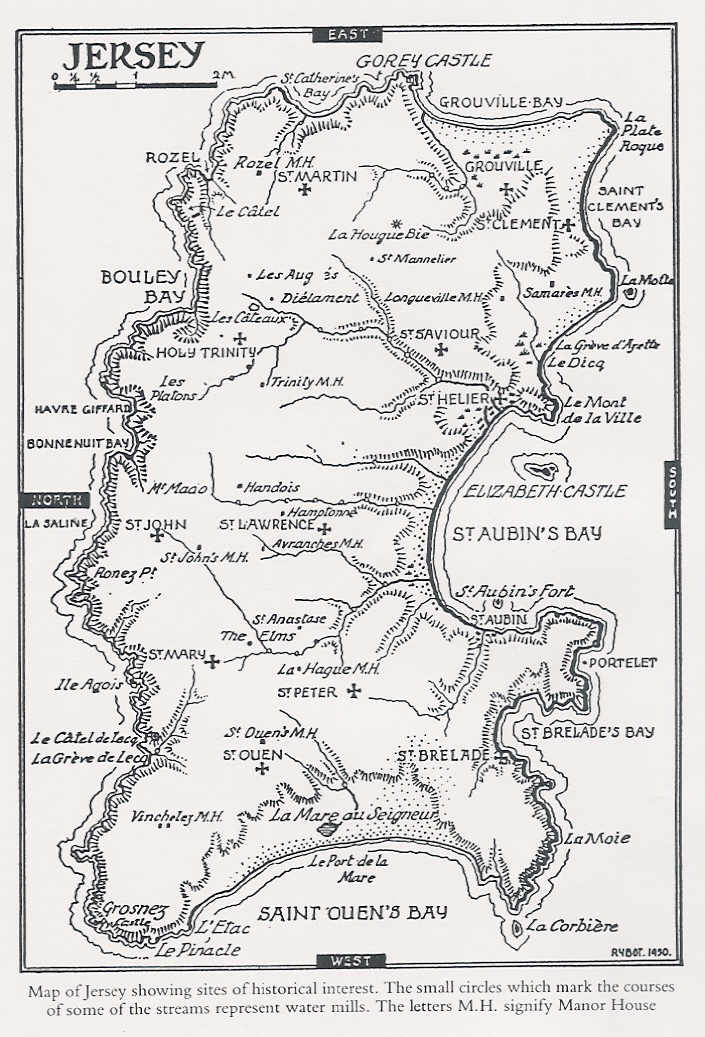

Jersey is one of the Channel Islands, which are located near the coast ofFrance

(Figure 4) but are under the sovereign rule of England.

Figure 4. Map showing location of Channel Islands in the English Channel near the coast ofNormandy in France. St.PeterPort is on the island of Guernsey. (Source: www.actionsites.com/maps/channel.htm )

Figure 5. Map of the island of Jersey, showing location of Elizabeth Castle in St Aubins Bay, near the capital, St. Helier. Note that north is to the left on this map.

From Rbyot’s history2 of Elizabeth Castle.

A brief overview of Jersey from Encyclopedia Online is given below. Images and photos of Elizabeth Castle, now a historical preserve and major tourist attraction, are shown in Figures 6 to 9.

Jersey

largest and southernmost of the Channel Islands, 12 miles (19 km) west of the Cotentin peninsula of France; its capital, St. Helier, is 100 miles south of Weymouth, Eng. Jersey is about 10 miles across and 5 miles from north to south and has an area of 44 square miles (115 square km). The Ecrehous rocks (6 miles northwest) and Les Minquiers (12 miles south) are in the Bailiwick of Jersey (area 45 square miles [116 square km]).

The island is largely a plateau mantled with loess, with deeply incised valleys sloping from north to south. Picturesque cliffs reaching 485 feet (148 m) in height line the northern coast; elsewhere, rocky headlands enclose sandy bays bordered by infilled lagoons. Coasts are reef-strewn, but a breakwater in St. Aubin’s Bay protects St. Helier harbour from southwest gales. Blown sand forms dunes at the northern and southern ends of St. Ouen’s Bay on the western coast. The climate is less maritime and more sunny than Guernsey’s. Mean annual temperature is 52 F (11 C). Frost is rare, but cold air spreading from France in spring occasionally damages the potato crop.

Prehistoric remains of Paleolithic man have been found at La Cotte de St. Brelade, and there is abundant evidence of the Neolithic and Bronze ages. The island was known to the Romans as Caesarea. Documents (11th century) show 12 parishes as part of the diocese of Coutances. In the 12th century, Norman landowners dominated the island, which was divided into three units for the collection of the king-duke’s revenue.

Separation from Normandy in 1204 made reorganization necessary. Jersey kept its Norman law and local customs but, with the other islands, was administered for the king by a warden and sometimes by a lord. By the end of the 15th century, Jersey had its own captain, later called governor, an office abolished in 1854, when the duties devolved upon a lieutenant governor, who still performs them. In 1617 it was ruled that justice and civil affairs were affairs of the bailiff. The Royal Court, as it came to be called, took the same form as Guernsey’s; the surviving court still reveals its medieval origin. The States of Jersey were separated from the Royal Court (1771) and assumed the court’s residual powers of legislation. Parish deputies were first elected in 1857.

In the 17th century the De Carterets, seigneurs of St. Ouen, dominated the island, holding it for the king from 1643 to 1651. In the 18th and 19th centuries the island was torn by feuds–Magots versus Charlots, Laurels versus Roses–but it also prospered from the Newfoundland fisheries, privateering, and smuggling, and, later, from cattle, potatoes, and the tourist trade.

Jersey is now governed under the British monarch in council by the Assembly of the States, in which the royally appointed bailiff presides over 12 senators, 12 constables (connétables), and 29 deputies, all popularly elected. The lieutenant governor and crown officers have seats and may speak but not vote. The Royal Court consists of the bailiff as chief magistrate and 12 jurats chosen by an electoral college. Judicial and legislative functions of jurats were not separated until 1948, when other reforms excluded from the States the rectors of the 12 parishes. The proceedings are conducted in French, the official language, though English is everywhere understood.

The inhabitants are mainly of Norman descent with an admixture of Breton, although there was an influx of English after 1830, of political refugees from Europe after 1848, and, after World War I, of men seeking to avoid taxation. St. Helier, the adjoining parishes of St. Saviour and St. Clement, Gorey, and St. Aubin are the main population centres.

Farming concentrates on dairying (with ancillary cropping) and on breeding for export of Jersey milk cattle, the only breed allowed on the island since 1789. Many small farms grow early potatoes and outdoor tomatoes for export. Greenhouse production of flowers, tomatoes, and vegetables is significant. Soil is fertilized with vraic (French varec, “wrack,” or “seaweed”) fertilizer. The tourist trade is well established. Knitting of the traditional woolen jerseys has declined. Passenger and cargo ships connect Jersey with Guernsey and Weymouth, Eng., and with Saint-Malo, Fr., via the ports of St. Helier and Gorey; and there are cargo services to London and Liverpool. Air links are extensive. Jersey Zoological Park was founded in 1959 in Trinity Parish by Gerald Durrell, the naturalist and writer, to protect animals in danger of extinction. Pop. (1981) 72,970.

Source: “Jersey” Encyclopædia Britannica, <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article?eu=44546> [Accessed January 7, 2003].

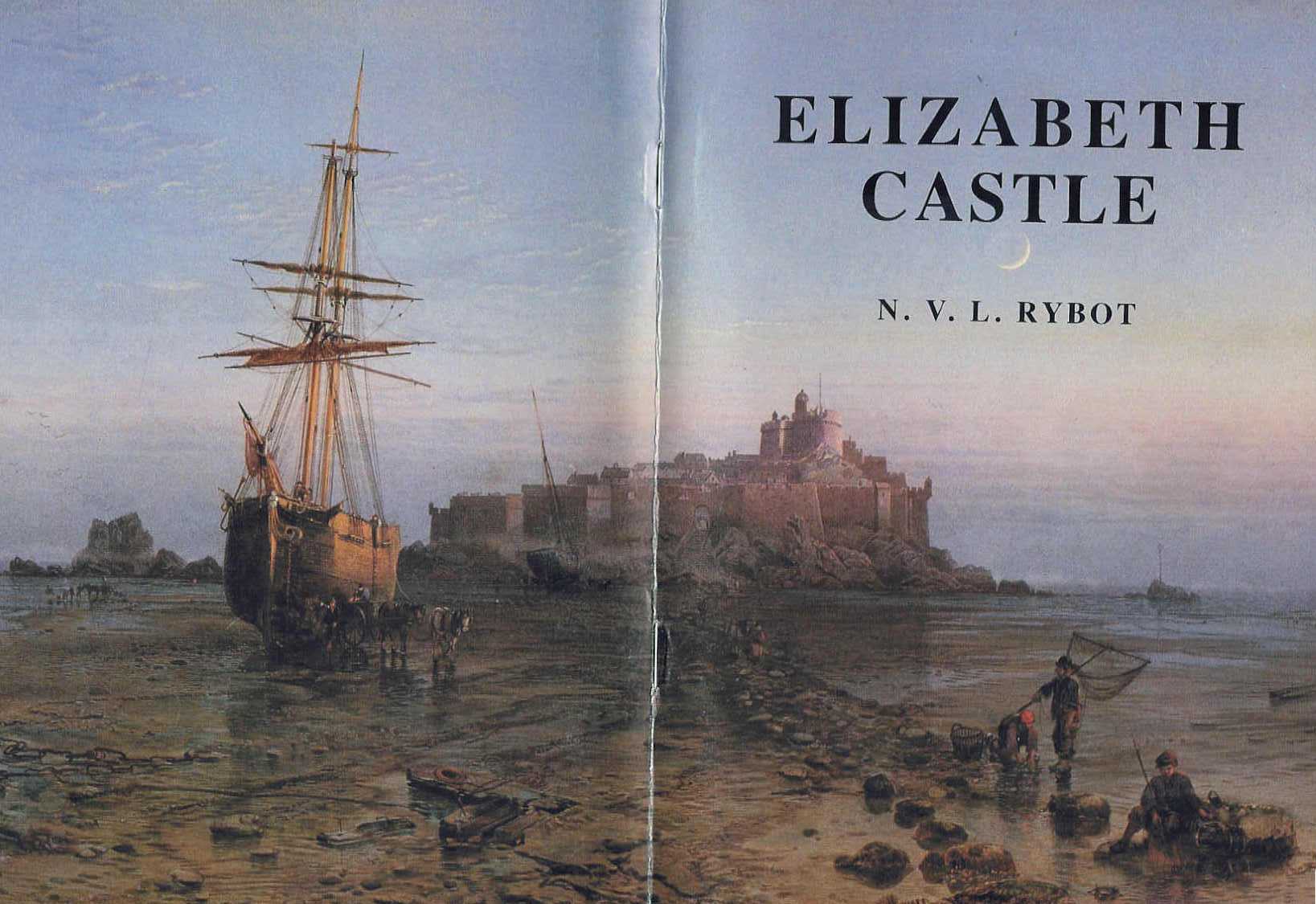

Figure 6. Painting showing Elizabeth Castle and adjoining tidal flats, from cover of history2 by Rybot.

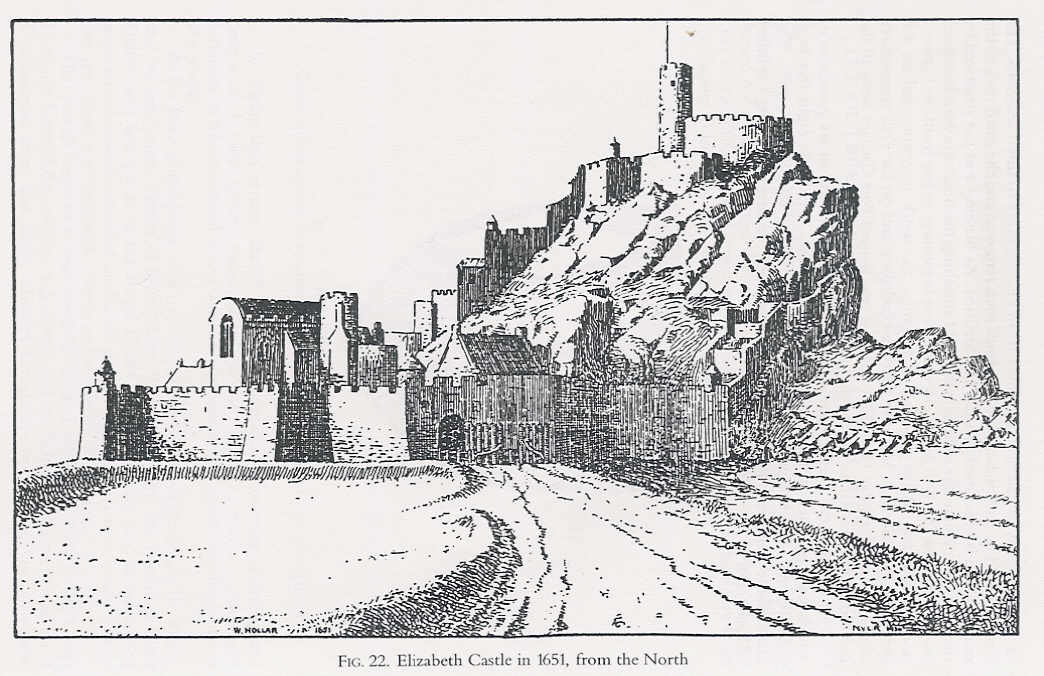

Figure 7. Line drawing of The Mount in Elizabeth Castle made in 1651, shortly after the second visit to the castle by Charles II. From Rybot’s history2 of Elizabeth Castle.

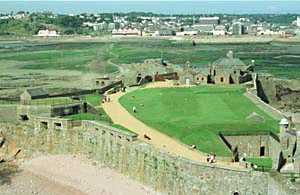

Figure 8. Recent photos of Elizabeth Castle. (Source: http://www.electric-image.co.uk/ec/elizabeth.html)

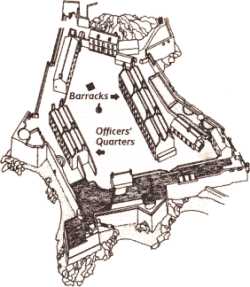

Figure 9. Drawings of Elizabeth Castle generally and of The Mount (Source: http://www.jerseyheritagetrust.org/sites)

Grimshaws on Jersey Today

Family research by Marjorie Grimshaw has resulted in a descendant chart for the Grimshaws on Jersey — it is summarized below. It has not yet been established if John Grimshaw is descended from the same line of Grimshaws as Mary Grimsha.

John Grimshaw (1800 – ) & Elizabeth ?

|—William John Grimshaw (1828 – ) & Annie ?

|—|—William John Grimshaw (1846 – 1913, St. Helier) & Alice Maud Jemima Heywood ( 21 Apr 1858 – 1938). Married 26 Apr 1877.

|—|—|—Clara Louise Grimshaw & William Brehaut

|—|—|—Albert Grimshaw & Kathleen O’Shea

|—|—|—|—Eight children

|—|—|—Charles Grimshaw & Bertha Plout

|—|—|—|—Bernard Grimshaw

|—|—|—|—Donald Grimshaw

|—|—|—Maud Grimshaw & William Brehaut (his second marriage after Clara)

|—|—|—William Edward Redway Grimshaw (15 Oct 1878, St. Helier 14 Oct 1917, St. Helier) & Margaret Ann Pinwill (18 Mar 1880 6 Sep 1952)

|—|—|—|—Frank Grimshaw (1899 – ?)

|—|—|—|—William Albert Grimshaw (16 Oct 1903, St. Helier -11 Sep 1965, St. Helier) & Eugenie Alphonsine Lucienne Marie (25 Sep 1904 20 Feb 1964). Married 9 Oct 1925.

|—|—|—|—|—Leslie Albert Grimshaw (5 Jun 1933, St. Helier- ) & Marjorie Gottrell (3 Jan 1933- ). Married 21 Jun 1955)

|—|—|—|—|—|—Living Grimshaw (25 Dec 1963- )

|—|—|—|—|—|—Living Grimshaw (3 Nov 1967 – ) & Living. Married 24 Oct 1996.

|—|—|—|—Sydney James Grimshaw (21 Aug 1904- 1970) & Elise Mahaute (1905 – 29 Oct 1994)

|—|—Annie Grimshaw (1849 -?)

|—|—Louisa Grimshaw (1853 – ?)

|—|—Henry Grimshaw (1859 – ?)

|—Ellen Grimshaw

|—Louisa Grimshaw

|—Elizabeth Grimshaw

References

1Toynbee, Margaret R., 1944, King Charles IIs “Charwoman”; in Notes and Queries for Readers, and Writers, Collectors and Librarians; v. 186, no. 7 (March 25, 1944), p. 150-152

2Rybot, N.V.L., 1986, Elizabeth Castle: Societe Jeriaise (Printed by Bigwoods Premier Printers), 139 p.

Webpage History

Webpage posted January 2003. Updated May 2004 with addition of research by Marjorie Grimshaw.