“Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret”

A Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne — Having Little or Nothing to Do With the Grimshaw Family

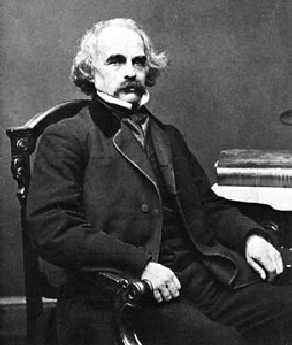

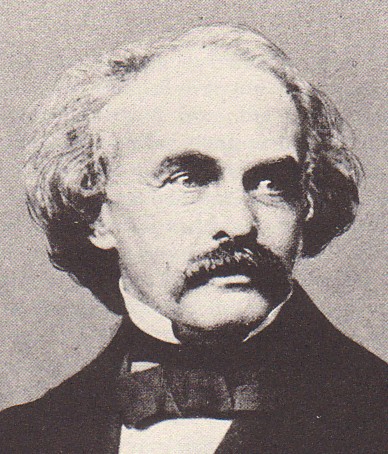

Image of Hawthorne from 1870 – several years after he wrote Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret

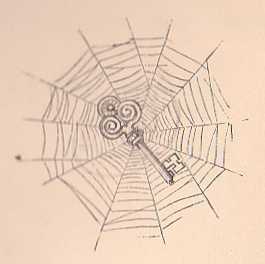

Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote Doctor Grimshawes Secret in 1861, but he never considered the work finished and did not publish it before his death. It was published posthumously in 1883, by Hawthornes son, Julian. Doctor Grimshawes Secret, according to literature historians, contains more autobiographical material than any of Hawthorne’s other writings. One of the principal topics is Hawthornes unresolved feelings about his childhood guardian, whose character is represented by Dr. Grimshawe, a spider-cultivating eccentric. The central motif (i.e., the “secret”) of the book is an all-encompassing spider web.

The Grimshawe name, probably learned when Hawthorne spent extensive time in England (he was the American consul in Liverpool for four years), was apparently picked because he felt that it fit the grim and foreboding character of the central character (i.e., Hawthornes guardian.) Thus neither the name nor the novel appear to have anything to do with members of the Grimshaw family.

Contents

Drawing of Doctor Grimshaw and Children

Hawthorne’s Handwriting of a Sample from the Book

Biographical Summary of Nathaniel Hawthorne

The First Chapter of “Doctor Grimshawes Secret

Gloria Erlichs Interpretive Analysis

Peabody House (aka Grimshawe House) – Setting for Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret

Where is Grimshawe House Located?

Webpage Credit

Thanks go to the staff in the Special Collections Department of the Marriott Library, the University of Utah, for making the original 1883 edition of Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret available for study and for scanning of the cover and title page.

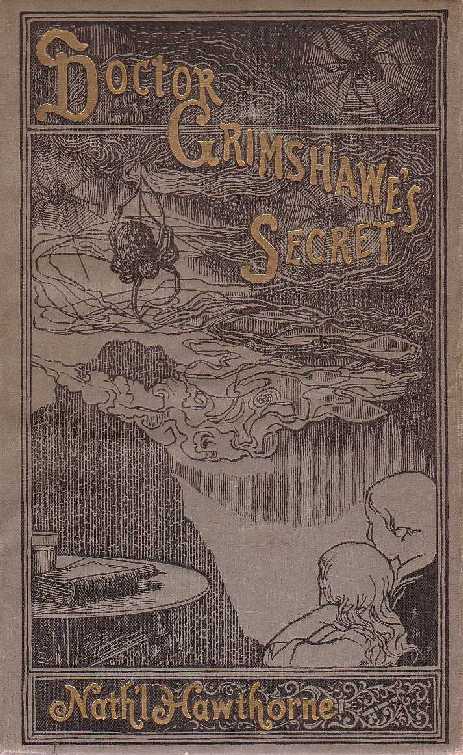

Cover and Title Page

The original published version of Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret1 (1883) has fascinating images both on the book cover and the title page. Both are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Cover and title page from Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret, showing images depicting the central themes of the book.

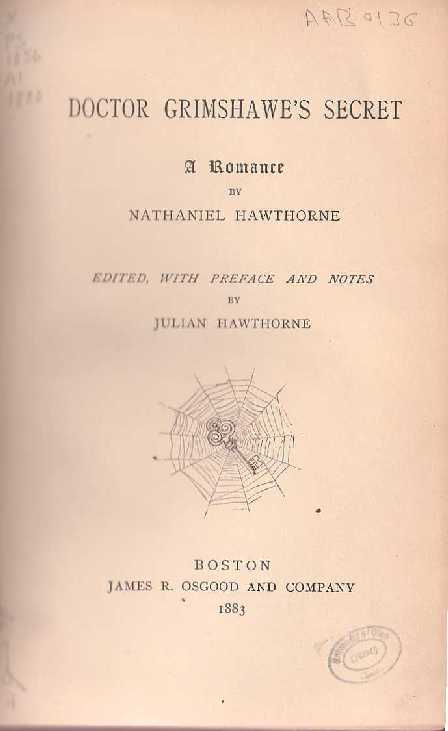

Drawing of Doctor Grimshaw and Children

A subsequent publication of Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret2, in 1890, included an interesting drawing of the main characters — the good doctor and the two children, Elsie and Ned — who were the main characters, as frontispiece (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Drawing of Doctor Grimshaw and the two children, the three main characters of the book.

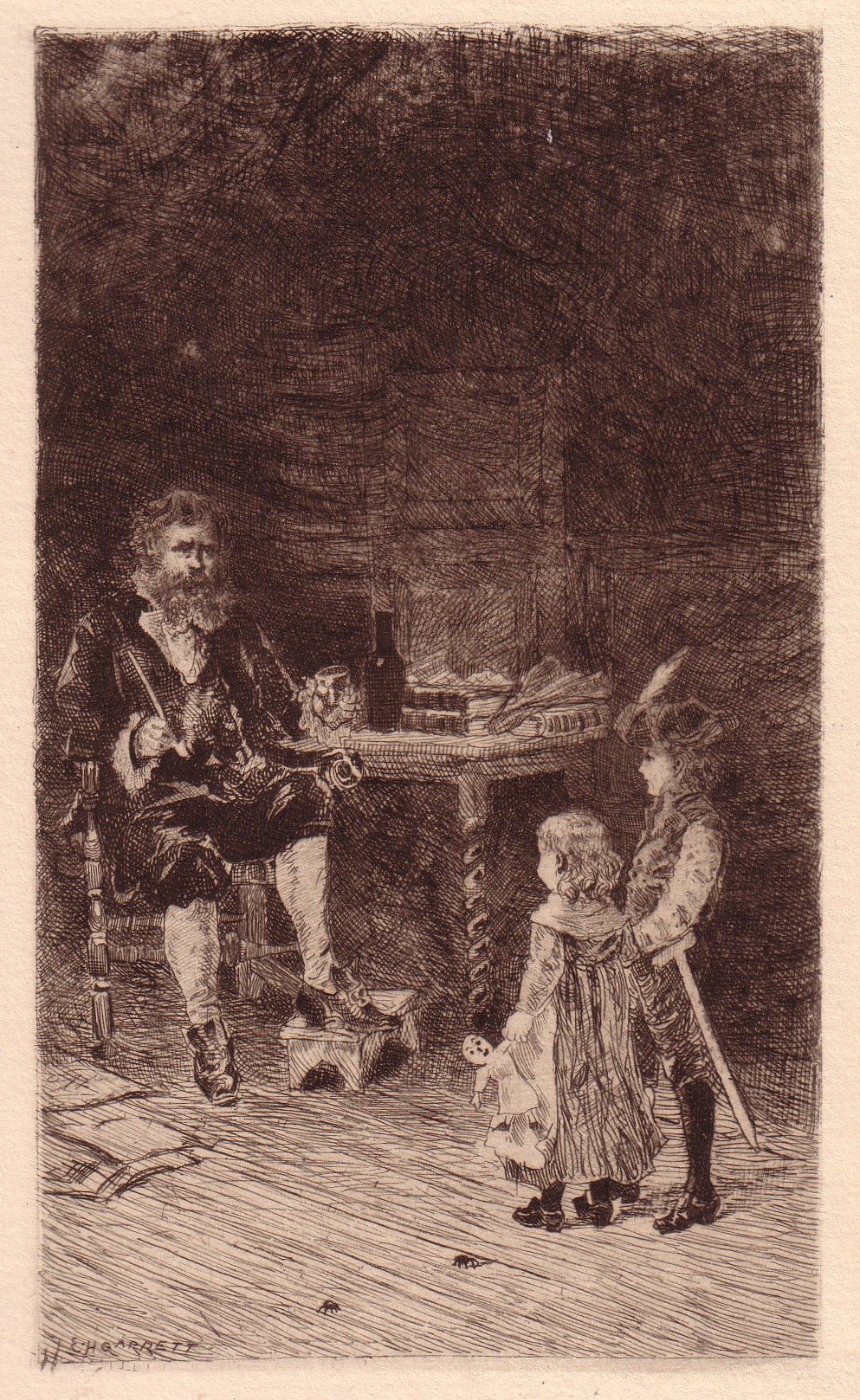

Hawthorne’s Handwriting in a Sample from the Book Manuscript

The 1890 edition of the book also included in the Preface a sample of the handwritten text from Hawthorne’s manuscript for Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret. This four-page sample is shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Sample pages of the original manuscript of “Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret”

Nathaniel Hawthorne: Biographical Summary

The photo of Hawthorne at the top of this webpage, taken in 1870, is from Hoeltje3. Another photo, taken eight years earlier, is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Photo of Hawthorne in 1862, the year after he wrote Doctor Grimshawes Secret.

A brief, concise biography of Hawthorne is provided by Encyclopedia Brittanica Online4 — it is provided below.

Nathaniel Hawthorne

American novelist and short-story writer who was a master of the allegorical and symbolic tale. One of the greatest fiction writers in American literature, he is best-known for The Scarlet Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851).

Born July 4, 1804 , Salem, Mass., U.S.; Died May 19, 1864, Plymouth, N.H.

Early years.

Hawthorne’s ancestors had lived in Salem since the 17th century. His earliest American ancestor, William Hathorne (Nathaniel added the w to the name when he began to write), was a magistrate who had sentenced a Quaker woman to public whipping. He had acted as a staunch defender of Puritan orthodoxy, with its zealous advocacy of a “pure,” unaffected form of religious worship, its rigid adherence to a simple, almost severe, mode of life, and its conviction of the “natural depravity” of “fallen” man. Hawthorne was later to wonder whether the decline of his family’s prosperity and prominence during the 18th century, while other Salem families were growing wealthy from the lucrative shipping trade, might not be a retribution for this act and for the role of William’s son John as one of three judges in the Salem witchcraft trials of 1692. When Nathaniel’s father —a ship’s captain — died during one of his voyages, he left his young widow without means to care for her two girls and young Nathaniel, aged four. She moved in with her affluent brothers, the Mannings. Hawthorne grew up in their house in Salem and, for extensive periods during his teens, in Raymond, Maine, on the shores of Sebago Lake. He returned to Salem in 1825 after four years at Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine. Hawthorne did not distinguish himself as a young man. Instead, he spent nearly a dozen years reading and trying to master the art of writing fiction.

First works.

In college Hawthorne had excelled only in composition and had determined to become a writer. Upon graduation, he had written an amateurish novel, Fanshawe, which he published at his own expense—only to decide that it was unworthy of him and to try to destroy all copies. Hawthorne, however, soon found his own voice, style, and subjects, and within five years of his graduation he had published such impressive and distinctive stories as “The Hollow of the Three Hills” and “An Old Woman’s Tale.” By 1832, “My Kinsman, Major Molineux” and “Roger Malvin’s Burial,” two of his greatest tales—and among the finest in the language—had appeared. “Young Goodman Brown,” perhaps the greatest tale of witchcraft ever written, appeared in 1835.

His increasing success in placing his stories brought him a little fame. Unwilling to depend any longer on his uncles’ generosity, he turned to a job in the Boston Custom House (1839-40) and for six months in 1841 was a resident at the agricultural cooperative Brook Farm, in West Roxbury, Mass. Even when his first signed book, Twice-Told Tales, was published in 1837, the work had brought gratifying recognition but no dependable income. By 1842, however, Hawthorne’s writing had brought him a sufficient income to allow him to marry Sophia Peabody; the couple rented the Old Manse in Concord and began a happy three-year period that Hawthorne would later record in his essay “The Old Manse.”

The presence of some of the leading social thinkers and philosophers of his day, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Thoreau, and Bronson Alcott, in Concord made the village the centre of the philosophy of Transcendentalism, which encouraged man to transcend the materialistic world of experience and facts and become conscious of the pervading spirit of the universe and the potentialities for human freedom. Hawthorne welcomed the companionship of his Transcendentalist neighbours, but he had little to say to them. Artists and intellectuals never inspired his full confidence, but he thoroughly enjoyed the visit of his old college friend and classmate Franklin Pierce, later to become president of the United States. At the Old Manse, Hawthorne continued to write stories, with the same result as before: literary success, monetary failure. His new short-story collection, Mosses from an Old Manse, appeared in 1846.

Mature novels.

A growing family and mounting debts compelled the Hawthornes’ return in 1845 to Salem, where Nathaniel was appointed surveyor of the Custom House by the Polk administration (Hawthorne had always been a loyal Democrat and pulled all the political strings he could to get this appointment). Three years later the presidential election brought the Whigs into power under Zachary Taylor, and Hawthorne lost his job; but in a few months of concentrated effort, he produced his masterpiece, The Scarlet Letter. The bitterness he felt over his dismissal is apparent in “The Custom House” essay prefixed to the novel. The Scarlet Letter tells the story of two lovers kept apart by the ironies of fate, their own mingled strengths and weaknesses, and the Puritan community’s interpretation of moral law, until at last death unites them under a single headstone. The book made Hawthorne famous and was eventually recognized as one of the greatest of American novels.

Determined to leave Salem forever, Hawthorne moved to Lenox, located in the mountain scenery of the Berkshires in western Massachusetts. There he began work on The House of the Seven Gables (1851), the story of the Pyncheon family, who for generations had lived under a curse until it was removed at last by love.

At Lenox he enjoyed the stimulating friendship of Herman Melville, who lived in nearby Pittsfield. This friendship, although important for the younger writer and his work, was much less so for Hawthorne. Melville praised Hawthorne extravagantly in a review of his Mosses from an Old Manse, and he also dedicated Moby Dick to Hawthorne. But eventually Melville came to feel that the friendship he so ardently pursued was one-sided. Later he was to picture the relationship with disillusion in his introductory sketch to The Piazza Tales and depicted Hawthorne himself unflatteringly as “Vine” in his long poem Clarel.

In the autumn of 1851 Hawthorne moved his family to another temporary residence, this time in West Newton, near Boston. There he quickly wrote The Blithedale Romance, which was based on his disenchantment with Brook Farm. Then he purchased and redecorated Bronson Alcott’s house in Concord, the Wayside. Blithedale was disappointingly received and did not produce the income Hawthorne had expected. He was hoping for a lucrative political appointment that would bolster his finances; in the meantime, he wrote a campaign biography of his old friend Franklin Pierce. When Pierce won the presidency, Hawthorne was in 1853 rewarded with the consulship in Liverpool, Lancashire, a position he hoped would enable him in a few years to leave his family financially secure.

Last years.

The remaining 11 years of Hawthorne’s life were, from a creative point of view, largely anticlimactic. He performed his consular duties faithfully and effectively until his position was terminated in 1857, and then he spent a year and a half sight-seeing in Italy. Determined to produce yet another romance, he finally retreated to a seaside town in England and quickly produced The Marble Faun. In writing it, he drew heavily upon the experiences and impressions he had recorded in a notebook kept during his Italian tour to give substance to an allegory of the Fall of man, a theme that had usually been assumed in his earlier works but that now received direct and philosophic treatment.

Back in the Wayside once more in 1860, Hawthorne devoted himself entirely to his writing but was unable to make any progress with his plans for a new novel. The drafts of unfinished works he left are mostly incoherent and show many signs of a psychic regression, already foreshadowed by his increasing restlessness and discontent of the preceding half dozen years. Some two years before his death he began to age very suddenly. His hair turned white, his handwriting changed, he suffered frequent nosebleeds, and he took to writing the figure “64” compulsively on scraps of paper. He died in his sleep on a trip in search of health with his friend Pierce.

Works.

The main character of The Scarlet Letter is Hester Prynne, a young married woman who has borne an illegitimate child while living away from her husband in a village in Puritan New England. The husband, Roger Chillingworth, arrives in New England to find his wife pilloried and made to wear the letter A (meaning adulteress) in scarlet on her dress as a punishment for her illicit affair and for her refusal to reveal the name of the child’s father. Chillingworth becomes obsessed with finding the identity of his wife’s former lover. He learns that Hester’s paramour is a saintly young minister, Arthur Dimmesdale, and Chillingworth then proceeds to revenge himself by mentally tormenting the guilt-stricken young man. Hester herself is revealed to be a compassionate and splendidly self-reliant heroine who is never truly repentant for the act of adultery committed with the minister; she feels that their act was consecrated by their deep love for each other. In the end Chillingworth is morally degraded by his monomaniac pursuit of revenge, and Dimmesdale is broken by his own sense of guilt and publicly confesses his adultery before dying in Hester’s arms. Only Hester can face the future optimistically, as she plans to ensure the future of her beloved little girl by taking her to Europe.

The House of the Seven Gables is a sombre study in hereditary sin based on the legend of a curse pronounced on Hawthorne’s own family by a woman condemned to death during the witchcraft trials. The greed and arrogant pride of the novel’s Pyncheon family down the generations is mirrored in the gloomy decay of their seven-gabled mansion, in which the family’s enfeebled and impoverished poor relations live. At the book’s end the descendant of a family long ago defrauded by the Pyncheons lifts his ancestors’ curse on the mansion and marries a young niece of the family.

In The Marble Faun a trio of expatriate American art students in Italy become peripherally involved to varying degrees in the murder of an unknown man; their contact with sin transforms two of them from innocents into adults now possessed of a mature and critical awareness of life’s complexity and possibilities.

Hawthorne’s high rank among American fiction writers is the result of at least three considerations. First, he was a skillful craftsman with an impressive arthitectonic sense of form. The structure of The Scarlet Letter, for example, is so tightly integrated that no chapter, no paragraph, even, could be omitted without doing violence to the whole. The book’s four characters are inextricably bound together in the tangled web of a life situation that seems to have no solution, and the tightly woven plot has a unity of action that rises slowly but inexorably to the climactic scene of Dimmesdale’s public confession. The same tight construction is found in Hawthorne’s other writings also, especially in the shorter pieces, or “tales.” Hawthorne was also the master of a classic literary style that is remarkable for its directness, its clarity, its firmness, and its sureness of idiom.

A second reason for Hawthorne’s greatness is his moral insight. He inherited the Puritan tradition of moral earnestness, and he was deeply concerned with the concepts of original sin and guilt and the claims of law and conscience. Hawthorne rejected what he saw as the Transcendentalists’ transparent optimism about the potentialities of human nature. Instead he looked more deeply and perhaps more honestly into life, finding in it much suffering and conflict but also finding the redeeming power of love. There is no Romantic escape in his works, but rather a firm and resolute scrutiny of the psychological and moral facts of the human condition.

A third reason for Hawthorne’s eminence is his mastery of allegory and symbolism. His fictional characters’ actions and dilemmas fairly obviously express larger generalizations about the problems of human existence. But with Hawthorne this leads not to unconvincing pasteboard figures with explanatory labels attached but to a sombre, concentrated emotional involvement with his characters that has the power, the gravity, and the inevitability of true tragedy. His use of symbolism in The Scarlet Letter is particularly effective, and the scarlet letter itself takes on a wider significance and application that is out of all proportion to its literal character as a scrap of cloth.

Works.

Hawthorne’s work initiated the most durable tradition in American fiction, that of the symbolic romance that assumes the universality of guilt and explores the complexities and ambiguities of man’s choices. His greatest short stories and The Scarlet Letter are marked by a depth of psychological and moral insight seldom equaled and never surpassed by any American writer.

Major Works:

Novels. Fanshawe, a Tale (1828); The Scarlet Letter (1850); The House of the Seven Gables (1851); The Blithedale Romance (1852); The Marble Faun: Or, the Romance of Monte Beni (British title, Transformation, 1860). (Unfinished novels): Septimius Felton (1872); The Dolliver Romance, and Other Pieces (1876); Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret (1883); The Ancestral Footstep (1883). Stories. Twice-Told Tales, including “The Gray Champion,” “The Gentle Boy,” “A Rill from the Town Pump,” “The Great Carbuncle,” “Sights from a Steeple,” and “Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment” (1837); 2nd enl. ed., including also “The Celestial Railroad” (1842); Mosses from an Old Manse (1846); The Snow-Image, and Other Tales (1851; also published as The Snow-Image, and Other Twice-Told Tales, 1852). (Stories for Children): Grandfather’s Chair (1841); Famous Old People (1841); Liberty Tree (1841); Biographical Stories for Children (1842); A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys (1851); Tanglewood Tales for Girls and Boys (1853). Biography. Life of Franklin Pierce (1852). Autobiographical. Our Old Home: A Series of English Sketches (1863); Passages from the American Note-Books of Nathaniel Hawthorne (1868); Passages from the English Note-Books of Nathaniel Hawthorne (1870); Passages from the French and Italian Note-Books of Nathaniel Hawthorne (1871).

The First Chapter of Doctor Grimshawes Secret

The text of the first chapter of Doctor Grimshawes Secret (original 1883 edition published by Julian Hawthorne) is provided below to demonstrate Hawthorne’s style and his character development of the grim Doctor Grimshawe. Two additional chapters are provided near the bottom of the webpage.

CHAPTER I

A long time ago, in a town with which I used to be familiarly acquainted, there dwelt an elderly person of grim aspect known by the name and title of Doctor Grimshawe, whose household consisted of a remarkably pretty and vivacious boy, and a perfect rosebud of a girl, two or three years younger than he, and an old maid-of-all-work, of strangely mixed breed, crusty in temper and wonderfully sluttish in attire. It might be partly owing to this handmaiden’s characteristic lack of neatness (though, primarily, no doubt) to the grim Doctor’s antipathy to broom, brush, and dusting-cloth) that the house – at least, in such portions of it as any casual visitor caught a glimpse of – was so overlaid with dust, that, in lack of a visiting card you might write your name with forefinger upon the tables; and so hung with cobwebs that they assumed the appearance of dusky upholstery.

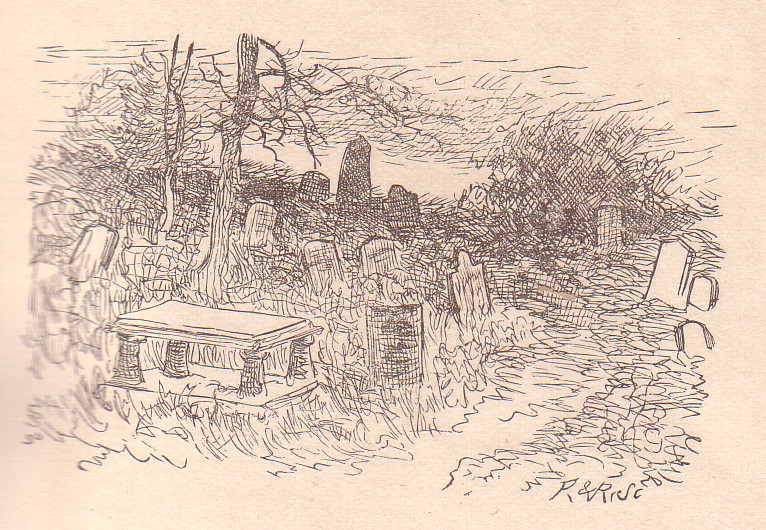

It grieves me to add an additional touch or two to the reader’s disagreeable impression of Doctor Grimshawe’s residence, by confessing that it stood in a shabby by-street, and cornered on a grave-yard, with which the house communicated by a back door; so that with a hop, skip, and jump, from the threshold across a flat tombstone, the two children were in the daily habit of using the dismal cemetery as their play-ground. In their graver moods, they spelled out the names and learned by heart doleful verses on the headstones; and in their merrier ones (which were much the more frequent) they chased butterflies, and gathered played hide and seek behind the slate and marble, and tumbled laughing over the grassy mounds which were too eminent for the short legs to bestride. On the whole, they were the better for the grave yard, and its legitimate inmates slept none the worse for the two children’s gambols and shrill merriment overhead. Here were old brick tombs with curious sculptures on them, and quaint gravestones, some of which bore puffy little cherubs, and one or two others the effigies of eminent Puritans, wrought out to a button, a fold of the ruf, and a wrinkle of the skull-cap; and these frowned upon the two children as if death had not made them a whit more genial than they were in life. But the children were of a temper to be more encouraged by the good-natured smiles of the puffy cherubs, than frightened or disturbed by the sour Puritans.

Drawing of Graveyard from 1890 Edition of Dr. Grimshawe’s Secret

This grave yard (about which we shall say not a word more than may sooner or later be needful) was the most ancient in the town. The clay of the original settlers had been incorporated with the soil; those stalwart= Englishmen of the Puritan epoch, whose immediate ancestors had been planted forth with succulent grass and daisies for the sustenance of the parson’s cow, round the low battlemented Norman church towers in the villages of the father-land, had here contributed their rich Saxon mould to tame and Christianize the wild forest earth of the new world. In this point of view – as holding the bones and dust of the primeval ancestors – the cemetery was more English than anything else in the neighborhood, and might probably have nourished English oaks and English elms, and whatever else is of English growth, without that tendency to spindle upward and lose their sturdy breadth, which it is said to be the ordinary characteristic both of human and vegetable growth, productions, when transplanted hither. Here, at all events, used to be some specimens of common English garden flowers, which could not be accounted for – unless, perhaps, they had sprung up from some English maiden’s heart, where the intense love of those homely things, and regret of them in this foreign land, had conspired together to keep their vivifying principle, and cause its growth after the poor girl was buried. Be that as it might, in this grave had been hidden from sight many a broad, bluff visage of husbandmen, who had been taught to plough among the hereditary furrows that had been ameliorated by the crumble of age: much had these sturdy laborers grumbled at the great roots that obstructed their toil in these fresh acres. Here, too, the sods had covered the faces of men known to history, and reverenced when not a piece of distinguishable dust remained of them; personages whom tradition told about; there, mixed up with successive crops of native born Americans, had been ministers, captains, matrons, virgins good and evil, tough and tender, turned up and battened down by the sexton’s spade, over and over again; until every blade of grass bad its relations with the human brotherhood of that old town. A hundred and fifty years was sufficient to do this; and so much time, at least had elapsed since the first hole was dug among the difficult roots of the forest trees, and the first little hillock of all these green beds was piled up.

Thus rippled and surged, with its hundreds of little billows, the old grave yard about the house which cornered upon it; it made the street gloomy, so that people did not altogether like to pass along the high wooden fence that shut it in; and the old house itself, covering ground which else had been sown thickly with buried bodies, partook of its dreariness, because it seemed hardly possible that the dead people should not get up out their graves, and steal in to warm themselves at the convenient fireside. But I never heard that any of them did so; nor were the children ever startled by spectacles of dim horror in the night-time, but were as cheerful and fearless as if no grave had ever yet been dug. They were of that class of children whose material seems fresh, not taken at second hand, full of disease, conceits, whims, weaknesses, that have already served many people’s turns, and moulded up, with some little change of combination, to serve the turn of some poor spirit that could not get a better case.

So far as ever came to the present writer’s knowledge, there was no whisper of Doctor Grimshawes house being haunted; a fact on which both writer and reader may congratulate themselves, the ghostly chord having been played upon, in these days, until it has become as wearisome and nauseous as the familiar tune of a barrel organ. The house itself, moreover, except for the convenience of its position, close to the seldom disturbed cemetery, was hardly worthy to be haunted. As I remember it (and, for aught I know, it still exists in the same guise) it did not appear to be an ancient structure, nor one that could ever have been the abode of a very wealthy or prominent family – a three-story wooden house perhaps a century old, low studded, with a square front, standing right upon the street, and a small enclosed porch, containing the main entrance affording a glimpse up and down the street through an oval window on each side, its characteristic was a decent respectability, not sinking below the boundary of the genteel. It has often perplexed my mind to conjecture what sort of man he could have been who, having the means to build a pretty spacious and comfortable residence, should have chosen to lay its foundation on the brink of so many graves; each tenant of these narrow houses crying out, as it were, against the absurdity of bestowing much time or pains in preparing any earthly tabernacle save such as theirs. But deceased people see matters from an erroneous – at least a too exclusive – point of view; a comfortable grave is an excellent possession for those who need it but a comfortable house has likewise its merits and temporary advantages.

The founder of the abode house in question seemed sensible of this truth, and had therefore been careful to lay out a sufficient number of rooms and chambers, low, ill-lighted, ugly, but not unsusceptible of warmth and comfort; the sunniest and cheerfulest of which were on the side that looked into the grave yard. Of these, the one most spacious and convenient had been selected by Doctor Grimshawe as a study, and fitted up with book shelves, and various machines and contrivances, electrical, chemical, and distillatory, wherewith he might pursue such researches as were wont to engage his attention. The great result of the grim Doctor’s labors, so far as known to the public, was a certain preparation or extract of cobwebs which, out of a great abundance of material, he was able to produce in any desirable quantity by the administration of which he professed to cure diseases of the inflammatory class and to work very wonderful effects upon the human systems. It is a great pity for the good of mankind, and the advantages of his own fortunes, that he did not put forth this medicine in pill-boxes or bottles, and then, as it were, by some captivating title, inveigle the public into his spider’s web, and suck out its golden substance, and himself wax fat in the central intricacy.

But grim Doctor Grimshawe, though his aim in life might be no very exalted one, seemed singularly destitute of the impulse to better his fortunes by the exercise of his wits: it might even have been supposed indeed that he had a conscientious principle, or religious scruple – only, he was by no means a religious man – against reaping profit from this particular nostrum which he was said to have invented. He never sold it; never prescribed it, unless in cases selected upon some principle that nobody could detect or explain. The grim Doctor, it must be observed, was not generally acknowledged by the profession, with whom, in truth, he had never claimed a fellowship; nor had ever assumed, of his own accord, the medical title by which the public chose to know him. His professional practice seemed, in a sort, forced upon him; it grew pretty extensive, partly because it was understood to be a matter of favor and difficulty, dependent on a capricious will, to obtain his services at all. There was unquestionably an odor of quackery about him; but by no means of an ordinary kind. A sort of mystery – yet which, perhaps, need not have been a mystery, bad anyone thought it worth while to make systematic inquiry – in reference to his previous life, his education, even his native land – assisted the impression which his peculiarities were calculated to make. He was evidently not a New Englander, nor a native of any part of these Western shores. His speech was apt to be oddly and uncouthly idiomatic, and even when classical in its form, was emitted with a strange, rough depth of utterance, that came from recesses of the lungs which we Yankees seldom put to any use. In person, he did not look like one of us; a broad, rather short personage, with a projecting forehead, red irregular face, and a squab nose; eyes that looked a dull enough in their ordinary state, but had a faculty, in conjunction with the other features, which those who had ever seen it described as especially ugly and awful. As regarded dress, Doctor Grimshawe had a rough and careless exterior, and altogether a shaggy kind of aspect, the effect of which was much increased by a reddish beard, which, contrary to the custom of the day, he allowed to grow profusely; and the wiry perversity of which seemed to know as little of the comb as of the razor.

We began with calling the grim Doctor an elderly personage; but, in so doing, we looked at him through the eyes of the two children who were his intimates, and who had not learnt to decipher the purport and value of his wrinkles and furrows and corrugations whether as indicating age or a different kind of wear and tear. Possibly – he appeared so vigorous, and had such latent heat and fire to throw out when occasions called, he might scarcely have seen middle aged; though here again we hesitate, finding him so stiffened into his own way, so little fluid, so encrusted with passions and humors, that he must have left his youth very far behind him; if indeed, he ever had any.

The patients, or whatever other visitors were ever admitted into the Doctor’s study, carried abroad strange accounts of the squalor of dust and cobwebs in which the learned and scientific person lived; and the dust, they averred, was all the more disagreeable because it could not well be other than dead men’s intangible atoms, resurrected from the adjoining grave-yard. As for the cobwebs, they were no tokens of housewifely neglect on the part of crusty Hannah, the handmaiden but the Doctor’s scientific material, carefully encouraged and preserved, each filmy thread more valuable to him than so much golden wire. Of all barbarous haunts in Christendom or elsewhere, this study was the one most overrun with spiders. They dangled from the ceiling, crept upon the tables, lurked in the corners, and wove the intricacy of their webs from point to point across the window panes, and even across the upper part of the doorway, and in the chimney-place. It seemed impossible to move without breaking some of these mystic threads. Spiders crept familiarly towards you, and walked leisurely across your hands; these were their precincts, and you only an intruder. If you saw none about your person, yet you had an odious sense of one crawling up your spine, or spinning cobwebs in your brain, – so pervaded was the atmosphere of this place with spiderlife. What they fed upon (for all the flies for miles roundabout would not have sufficed them) was a secret known only to the Doctor. Whence they came was another riddle; though, from certain inquiries and transactions of Doctor Grimshawes with some of the shipmasters of the port, who followed the East or West Indian, the African, or the South American trade, it was supposed that this odd philosopher was in the habit of importing choice monstrosities in the spider kind from all those tropic regions.

All the above description, exaggerated as it may seem, is merely preliminary to the introduction of one single, enormous spider, the biggest and the ugliest ever seen, the pride of the grim Doctor’s heart, his treasure, his glory, the pearl of his soul, and, as many people said, the demon to whom he had sold his salvation, on condition of possessing the web of the foul creature for a certain number of years. The grim Doctor, according to this theory, was but a great fly which this spider had subtly entangled in his web. But, in truth, naturalists are acquainted with this spider, though it be a rare one; the British Museum has a specimen, and, doubtless, so have many other scientific institutions. It is found in South America, its most hideous spread of legs covering a space nearly as large as a dinner-plate, and radiating from a body as big as a door knob, which one conceives to be an agglomeration of sucked up poison, which the creature treasures through life, probably, to expend it all, and life itself, on some worthy foe. Its colors were variegated in a sort of ugly and inauspicious splendor, were distributed over its vast bulb in great spots, some of which glistened like gems. It was a horror to think of this thing living; still more a horror to think of the foul catastrophe, the crushed out and wasted poison, that would follow the casual setting a foot upon it.

No doubt, the lapse of time, since the Doctor and his spider lived, has already been sufficient to cause a traditionary wonderment to gather over them both; and especially this image of a spider dangles down to us from the dusky ceiling of the Past, swollen into somewhat huger and uglier monstrosity than he actually possessed, Nevertheless, the creature had a real existence, and has left kindred like himself; and as for the Doctor, nothing could exceed the value which he seemed to put upon him, the sacrifices which he made for the creature’s convenience, or the readiness with which he adapted his whole mode of life, apparently, so that the spider might enjoy the conditions best suited to his tastes, habits, health. And yet there were sometimes tokens that made people imagine that he hated the infernal creature as much as everybody else who caught a glimpse of him.

(From the title page of the original published edition of Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret)

Gloria Erlichs Interpretive Analysis

An excellent analysis of Doctor Grimshawes Secret was prepared by Gloria Erlich5 in a more comprehensive work on Hawthorne. Chapter 5 of her work, which focuses on the unfinished romance, is provided on a companion webpage. The contents and initial paragraphs of the analysis in Chapter 5 are shown below.

CHILDHOOD ON THE EDGE OF A CEMETERY

FIVE

Doctor Grimshawe and Other Secrets

Such whenas Archimago them did view, He weened well to worke some uncouth wile, Eftsoones untwisting his deceiptfull clew, He gan to weave a web of wicked guile.

The Faerie Queene, II, 8

[Doctor Grimshawe] must have the air, in the Romance, of a sort of magician, without being called so; and even after his death, his influence must still be felt. Hold on to this. A dark, subtle manager, for the love of managing, like a spider sitting in the center of his web, which stretches far to east and west.

Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret

ARCHIMAGO’S WEB

Until the very end of his life, perhaps especially at the end of it, Hawthorne struggled with unresolved feelings about his guardian. Of all his works, Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret contains the most autobiographical material and is the most preoccupied with father substitutes. Feeding into this unfinished work are materials drawn from the author’s own life experiences-his emotional return to the land of his fathers, his early reading in Spenser, and residual feelings about his own childhood. All four of the late romances deal with personal preoccupations of the sick and aged author. To a greater or lesser degree, these works focus on a central set of symbols and situations that Hawthorne seemed unable to discard even when he was unsure of their meaning and value. Among these are the scientist whose demon or familiar is an enormous spider, an American claimant to an ancestral English estate, and the legend of the Bloody Footstep.

(See companion webpage for additional text of Erlich’s analysis).

Where was Hawthorne Born?

Hawthorne was born in Salem, Massachusetts on July 4, 1804 (Figure 3); his father, a ship’s captain, died when Nathaniel was only four years old. His mother went to live with her affluent brothers (the Mannings) in Salem. Hawthorne was raised in their home .

Figure 3. House in Salem (27 Union Street) where Hawthorne was born in 1804.

Source:

http://www.hawthorneinsalem.org/Architecture/HousesinSalem/HawthornesHouse/Introduction.html

Peabody House (aka Grimshawe House) – Setting for Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret

Hawthorne married Sophia Peabody in 1842. When he was courting Sophia, she was living with her family (her father was a dentist) at 53 Charter Street in Salem, Massachusetts. The home was a large three-story building known as the “Peabody House”. Later, Hawthorne used the house as the setting for Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret and it has since received the moniker “Grimshawe House”. Two views of the house are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Two views of Grimshawe House at 53 Charter Street in Salem, Massachusetts

Sources: http://www.hawthorneinsalem.org/images/image.php?name=MMD6;

Robin Emrich has posted on the internet the following interesting image of the entry to Grimshawe House, along with a few descriptive words (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Robin Emrich’s drawing of the Grimshawe House entry with explanatory text

Grimshaw House

The Grimshaw (sic) House is 1 of 4 pieces created in early 1999. The historic significance of this building is its relationship to Nathaniel Hawthorne. This is where he courted his wife, Sophia Peabody. The house still stands and is bordered by one of the oldest graveyards in Salem, which sits on a raised expanse that abuts directly against the house midway up the first floor. It is known that Sophia’s father was a dental surgeon … dentist’s had far reaching roles in the 1800’s and often dealt with life threatening abscesses and other ailments much beyond what we attribute to today’s modern dentistry. The parlor of the house (also the waiting room) conveniently overlooks the graveyard. Many was the patient who may have pondered their own future and the course of their treatments as they sat patiently looking out into the scene that would often include a funeral or two for their more morbid thoughts to ponder and reflect upon. Certainly the morose and macabre nature of the building and its surrounds helped to ferment and inspire some of Hawthorne’s marvelous creativity. Alas, the building still stands (behind the Essex Museum) in most perfunctory dishevel reflecting most accurately the lost souls it has encountered over its lifetime. This particular proof is a first generation one, a significantly more handsome one is available that includes an aquatint which further accentuates the mood and tone of the structure in its present day terms. The plate size is 9.5″x13.75″.

Where is Grimshawe House Located?

As noted, Grimshawe House is located in Salem at 53 Charter Street (Figure 6). The house is not far from the setting of the novel “House of Seven Gables” (The Turner-Ingersoll House at 54 Turner St) and the “Witch House” (Jonathan Corwin house, 310 ½ Essex St at North St), where witches were purportedly examined during the witch trials of 1692 – in which 19 people were hanged.

Figure 6. Maps showing the location of Salem, Massachusetts about 20 miles northeast of Boston and the location of Grimshawe House in Salem (red stars)

Chapters Two and Three of Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret

The first chapter of Hawthorne’s book is presented above. Two additional chapters are provided below for further exposition of his style of writing and portrayal of the character Doctor Grimshawe.

CHAPTER II.

Considering that Doctor Grimshawe, when we first look upon him, had dwelt only a very few years in the house by the grave-yard, it is wonderful what an appearance he and his furniture, and his cobwebs, and their unweariable spinners, and crusty old Hannah, all had, of having permanently attached themselves to the locality. For a century, at least, it might be fancied that the study in particular had existed just as it was now, with those dusky festoons of spider silk hanging along the walls, those book-cases with volumes, turning their parchment or black leather backs upon you, those machines and engines, that table, and at it the Doctor, in a very faded and shabby dressing gown, smoking a long clay pipe, the powerful fumes of which dwelt continually in his reddish and grisly beard, and made him fragrant wherever he went. This sense of fixedness – stony intractability – seems to belong to people who, instead of hope, which exalts everything into an airy, gaseous exhilaration, have a fixed and dogged purpose, around which everything congeals and crystallizes. Even the sunshine, dim through the dustiness of the two casements that looked upon the graves, and the smoke, as it came warm out of Doctor Grimshawe’s mouth, seemed already stale. But if the two children, or either of them, happened to be in the study, – if they ran to open the door at the knock, if they came scampering and peeped down over the banisters – the sordid and rusty gloom was apt to vanish quite away. The sunbeam itself looked like a golden rule that had been flung down long ago, and had lain there till it was dusty and tarnished. They were cheery little imps, who sucked up fragrance and pleasantness out of their surroundings, dreary as these looked, even as a flower can find its proper fragrance in any soil where its seed happens to fall. The great spider, hanging by his cordage over the Doctor’s head, and waving slowly, like a pendulum, in a blast from the crack of the door, must have made millions and millions of precisely such vibrations as these; but the children were new, and made over every day, with yesterdays wearness left out. They were new, and made over every moment, with yesterday’s weariness left out.

The little girl, however, was the merrier of the two. It was quite unintelligible, in view of the little care that crusty Hannah took of her, and, moreover, that she was none of your prim, children, how daintily she kept herself amid all this dust; how the spider’s webs never clung to her; and how – when without being solicited – she clambered into the Doctor’s arms and kissed him, she bore away no smoky reminiscences of the pipe that he kissed continually. She had a free, mellow, natural laughter, that seemed the ripened fruit of the smile that was generally on her little face, and to be shaken off and scattered abroad by any breeze that came along. Little Elsie made playthings of everything, even of the grim Doctor, though against his will, and though, moreover, there were tokens now and then, that the sight of this bright little creature was not a pleasure to him, but, on the contrary a positive pain; a pain, nevertheless, indicating a profound interest, hardly less deep than if Elsie had been his daughter.

Elsie did not play with the great spider, but she moved among the whole host of spiders as if she saw them not, and being endowed with other senses than those allied to these things, might coexist with them and not be sensible of their presence. Yet the child, I suppose, had her crying fits, and her pouting fits, and naughtiness enough to entitle her to live on earth; at least, crusty Hannah often said so, and often made grievous complaint of disobedience, mischief, breakage, attributable to little Elsie; to which the grim Doctor seldom responded by anything more intelligible than a puff of tobacco smoke, and sometimes an imprecation; which, however, hit crusty Hannah instead of the child. Where the child got the tenderness which a child needs to live upon is a mystery to me; perhaps from some aged or dead mother, or in her dreams; perhaps from some small modicum of it, such as boys have, from the little boy; or perhaps it was from a Persian kitten, which had grown to be a cat in her arms, and slept in her little bed, and now assumed grave and protective airs towards her former playmate.

The boy, as we have said, was two or three years Elsie’s elder, and might now be about six years old He was a healthy and cheerful child, yet of a graver mood than the little girl, appearing to lay a more forcible grasp on the circumstances about him, and to tread with a heavier footstep on the solid earth; yet perhaps not more so than was the necessary difference between a man-blossom, dimly conscious of coming things, and a mere baby, with whom there was neither past nor future. Ned, as he was named, was subject very early to fits of musing, the subject of which – if they had any definite object, or were more than vague reveries – it was impossible to guess. They were of those states of mind, probably, which are beyond the sphere of human language, and would necessarily lose their essence in the attempt to communicate or record them. The little girl, perhaps, had some mode of sympathy with these unuttered thoughts or reveries, which grown people had ceased to have; at all events, she early. learned to respect them, and, at other times as free and playful as her Persian kitten, she never in such circumstances ventured on any greater freedom, in such circumstances, than to sit down quietly beside him, and endeavor to look as thoughtful as the boy himself.

Once, slowly emerging from one of these waking dreams, little Ned gazed about him, and saw Elsie sitting with this pretty pretence of thoughtfulness and dreaminess, in her little chair, close beside him; now and then peeping under her eyelashes to note what changes might come over his face. After looking at her a moment or two, he quietly arose and taking her willing and warm little hand in his own, led her up to the Doctor.

This group, methinks, was a picturesque one, made up of several apparently discordant elements, each of which happened to be so combined as to make a more effective whole. The beautiful, grave boy, with a little sword by his side and a feather in his hat, of a brown complexion, slender, with his white brow, and dark, thoughtful eyes, so earnest upon some mysterious theme; the prettier little girl, a blonde, round, rosy, so truly sympathetic with her companion’s mood, yet unconsciously turning all into sport by her attempt to assume one similar – these two, standing at the grim Doctor’s footstool; he, meanwhile, black, wild-bearded, heavy-browed, red-eyed, wrapped in his faded dressing gown, puffing out volumes of vapor from his long pipe, and making, just at that instant, application to a tumbler, which, we regret to say, was generally at his elbow, with some dark-colored potation in it, which required to be frequently replenished from a neighboring black bottle. Half, at least, of the fluids in the grim Doctor’s system must have derived from that same black bottle, so constant was his familiarity with its contents; and yet his eyes were never redder at one time than another, nor his utterance thicker, nor his wits less available, nor his mood perceptibly the brighter or the darker for all his conviviality. It is true, when, once the bottle happened to be empty for a whole day together, Doctor Grimshawe was observed by crusty Hannah and by the children, to be considerably fiercer than usual: so that probably, by some maladjustment of consequences, his intemperance was only to be found in refraining from brandy.

Nor must we forget – in attempting to conceive the effect of these two beautiful children in such a sombre room, looking on the graveyard, and contrasted with the grim Doctor’s aspect of heavy and smouldering fierceness – that over his head, at this very moment, dangled the portentous spider, who seemed to have come down from his web aloft for the very purpose of hearing what the two young people could have to say to his patron, and what reference it might have to certain myserious documents which the Doctor kept locked up in a secret cupboard behnd the door.

“Grim Doctor,” said Ned, after looking up into the Doctor’s face, as a sensitive child inevitably does, to see whether the occasion was favorable, yet determined to proceed with his purpose, whether so or not, – “Grim Doctor, I want you to answer me a question.”

“Here’s to your good health, Ned!” quoth the Doctor, eying the pair intently, as he often did, when they were unconscious. “So you want to ask me a question? As many as you please, my fine fellow; and I shall answer as many, and as much, and as truly as may please myself.”

“Ah, grim Doctor!” said the little girl, now letting go of Ned’s hand and climbing upon the Doctor’s knee, “‘ou shall answer as many as Ned please to ask, because to please him and me.”

‘Well, child,” said Doctor Grimshawe, “little Ned will have his rights, at least, at my hands, if not other people’s rights likewise; and, if it be right, I shall answer his question. Only, let him ask it at once; for I want to be busy thinking about something else.”

“Then, Doctor Grim,” said little Ned, “tell me, in the first place, where I came from, and how you came to have me.”

The Doctor looked at the little man, so seriously and earnestly putting this demand, with a perplexed, and at first, it might almost seem, a startled aspect.

“This is a question, indeed, my friend Ned!” ejaculated he, putting forth a whiff of smoke and imbibing a sip of his tumbler before he spoke; and perhaps framing his answer, as many thoughtful and secret people do, in such a way as to let out his secret mood to the child, because knowing he could not understand it: “Whence did you come? Whence did any of us come? Out of the darkness and mystery; out of nothingness: out of a kingdom of shadows; out of dust, clay, mud, I think, and to return to it again. Out of a former state of being, whence we have brought a good many shadowy revelations purporting that it was no very pleasant one. Out of a former life, of which this present one is the hell! – And why are you come? Faith, Ned, he must be a wiser man than Doctor Grim who can tell why you, or any other mortal came hither; only one thing I am well aware of, – it was not to be happy. To toil, and moil, and hope, and fear, and to love in a shadowy, doubtful sort of way, and to hate in bitter earnest, – that is what you came for!”

“Ah, Doctor Grim! this is very naughty,” said Elsie. “You are making fun of little Ned, when he is in earnest!”

“Fun,” quoth the Doctor, bursting into a laugh peculiar to him, very loud and obstreperous. “I am glad you find it so, my little woman! Well; and so you bid me tell absolutely where he came from.

Elsie nodded her bright, little head.

“And you, friend Ned, insist upon knowing?” continued the Doctor.

“That I do, Doctor Grim!” answered Ned. His white, childish brow had gathered into a frown, such was the earnestness of his determination; and he stamped his foot on the floor, as if ready to follow up his demand by an appeal to the little tin sword which hung by his side. The Doctor looked at him with a kind of smile, – not a very pleasant one; for it was a not very amiable characteristic of his temper, that a display of spirit, even in a child, was apt to arouse his immense combativeness, and make him aim a blow, without much consideration how heavily it might fall, or on how unequal an antagonist.

“If you insist upon an answer, Master Ned, you shall have it,” replied he. “You were taken by me, boy, a foundling, from the alms house; and if ever hereafter you desire to know your kindred, you must take your chance of the first man you meet. He is as likely to be your father as another!”

The child’s eyes flashed, and his brow grew as red as fire. It was but a momentary fierceness; the next instant, he clasped his hands over his face, and wept in a violent convulsion of grief and shame. Little Elsie clasped her arms about him, kissing his brow and chin, which were all that her lips could touch under his clasped hands; but Ned turned away, uncomforted, and was blindly making his way towards the door.

“Ned, my little fellow, come back!” said Doctor Grim, who had very attentively watched the cruel effect produced by his communication.

As the boy did not reply, and was still tending towards the door, the grim Doctor vouchsafed to lay aside his pipe, get up from his arm-chair (a thing he seldom did between supper and bedtime) and shuffle after the two children in his slippers. He caught them on the threshold, brought little Ned back, by main force, – for he was a rough man, even in his tenderness, and, – sitting down again, and taking him on his knee, pulled away his hands from before his face. Never was a more pitiful sight than that pale countenance, so infantile still, and yet looking old and experienced already, with a sense of disgrace, with a feeling of loneliness; so beautiful, nevertheless, that it seemed to possess all the characteristics which fine hereditary traits, and culture in many forefathers, could do in refining a human stock. And this, then, was a nameless weed, sprouting from chance seed by the dusty wayside!

“Ned, my dear old boy,” said Doctor Grim; and he kissed that pale, tearful face, – the first and the last time, to the best of my belief, that he was ever betrayed into such tenderness; “forget what I have said! Yes; remember, if you like, that you came from an alms-house; but, remember, too, what your friend Doctor Grim is ready to affirm and make oath of; – that he can trace your kindred and race through that sordid experience, and back, back for a hundred and fifty years, into an old English line. Come, little Ned, and look at this picture!”

He led the boy by the hand into a comer of the room, where hung upon the wall a portrait, which Ned had often looked at. It seemed an old picture, but the Doctor had had it cleaned and varnished, so that it looked dim and dark; and yet it seemed to be the representation of a man of no mark, or such mark in life as would naturally leave his features to be transmitted for the interest of another generation; for he was clad in a mean dress, of old fashion, – a leather jerkin it appeared to be, and round his neck, moreover, was a noose of rope, as if he might have been on the point of being hanged. But the face of the portrait, nevertheless, was beautiful, noble, though sad; with a great development of sensibility, a look of suffering and endurance, amounting to triumph, – a peace through all.

“Look at this,” continued the Doctor. “If you must go on dreaming about your race, dream that you come of the blood of this being; for, mean as his station looks, he comes of an ancient and noble race, and was the noblest of them all. Let me alone, Ned; and I shall spin out the web that shall link you with that race. The grim Doctor can do it.”

The grim Doctor’s face looked fierce with the earnestness with which he said these words. You would have said that he was taking an oath to overthrow and annihilate a race, rather than to build one up, by bringing forward the infant heir out of obscurity, and making plain the links – the filaments, – which connected that feeble childish life, in a far country, with the great tide of a noble life, which had come down like a chain from antiquity, in old England.

Having said these words, the grim Doctor appeared ashamed both of the heat and tenderness into which he had been betrayed; for rude and rough as his nature was, there was a kind of decorum in it, too, that kept him within limits of his own. So he went back to his chair, his pipe, and his tumbler, and was gruffer and more taciturn than ever, for the rest of the evening. And, after the children went to bed, he leaned back in his chair, and looked up at the vast tropic spider, who was particularly busy in adding to the intricacies of his webs; until he fell asleep with his eyes fixed in that direction, and the extinguished pipe in one hand, and the empty tumbler in the other.

CHAPTER III.

Doctor Grimshawe, after the foregone scene, began a practice of conversing more with the children than formerly; directing his discourse chiefly to Ned, although Elsie’s vivacity and more outspoken and demonstrative character made her take quite as large a part in the conversation as he.

The Doctor’s communications referred chiefly to a village, or neighborhood, or locality, in England which he chose to call Newnham; although he told the children that this was not the real name, which, for reasons best known to himself, he chose to conceal. Whatever the name were, he seemed to know the place so intimately, that the children, as a matter of course, adopted the conclusion that it was his birth-place, and the spot where he had spent his school-boy days, and had lived until some inscrutable reason impelled him to quit its ivy-grown antiquity, all the aged beauty and strength that he spoke of, and cross the sea.

He used to tell of an old church, far unlike the brick or pine-built meeting-houses with which they were familiar; a church, the stones of which were laid, every one of them, before the world knew of the country in which he was then speaking: and how it had a spire, the lower part of which was mantled with ivy, and up which, towards its very top, the ivy was still creeping; and how there was a tradition, that, if the ivy ever reached the top, the spire would fall upon the roof of the old gray church, and crush it all down among its surrounding tombstones. And so, as this misfortune would be so heavy a one, there seemed to be a miracle wrought from year to year, by which the ivy, though always flourishing, could never grow beyond a certain point; so that the spire and church had stood unharmed for thirty years; though the wise old people were constantly foretelling that the passing year must be the very last one that it could stand.

He told, too, of a kind of place that made little Ned blush and cast down his eyes, to hide the tears of shame and anger at he knew not what, which would irresistibly spring into them; for it reminded him of the almshouse which, as the cruel Doctor had said, Ned himself had had his earliest home. And yet, after all, it had scarcely a feature of resemblance; and there was this great point of difference, – that, whereas in Ned’s wretched abode, (a large unsightly brick house) there were many wretched infants like himself, as well as helpless people of all ages, widows, decayed drunkards, people of feeble wit, and all kinds of imbecility; it being a haven for those who could not contend with the hard, eager, pitiless struggle of life; in the place that the Doctor spoke of, a noble, Gothic, mossy structure, there were none but aged men who had drifted into this quiet harbor to end their days in a sort of humble yet stately ease and decorous abundance. And this shelter, the grim Doctor said, was the gift of a man who died hundreds and hundreds of years ago; and being a great sinner in his lifetime, and having drawn lands, manors, a great mass of wealth into his clutches, by violent and unfair means, this man had thought to get his pardon by founding this hospital, as it was called, in which thirteen poor old men should always reside; and he hoped they would spend their time in praying for his soul.

Said little Elsie, “I am glad he did it, and I hope the poor old men never forgot to pray for him, and that it did good to the poor wicked man’s soul.”

“Well, child,” said Doctor Grimshawe, with a scowl into vacancy, and a kind of wicked leer of merriment, at the same time, as if he saw the dead man of past centuries now before him, “I happen to be no lover of this man’s race, and I hate him for the sake of one of his descendants. I don’t think he succeeded in bribing the devil to let him go, or God to save him.”

“Doctor Grim, you are very naughty,” said Elsie, looking shocked.

“It is fair enough,” said Ned, “to hate your enemy to the very brink of the grave, but then to leave him to get what mercy he can.”

“After shoving him in!” quoth the Doctor; and made no response to either of these criticisms, which seemed, indeed, to affect him very little, – if he even listened to them. For he was a man of singularly imperfect moral culture; insomuch that nothing was so remarkable about him as that – possessing a good deal of intellectual ability made available by much reading and experience – he was so very dark on the moral side; as if he needed the natural perceptions that should have enabled him to acquire that better wisdom. Such a phenomenon often meets us in life; oftener than we recognize, because a certain tact and exterior decency hides generally hide the moral deficiency; but often there is a mind well polished, and a conscience and natural passions left as they were in childhood, except that they have sprouted up into evil and poisonous weeds, richly blossoming, with strong smelling flowers or seeds which it scatters by a sort of impulse, as the Doctor was now half-consciously throwing seeds of his evil passions into the minds of these children. He was himself a grown-up child, without tact, simplicity, and innocence, and ripened evil, all the ranker for a native heat that was in him, and still active, and that might have nourished good things as it did evil. Indeed, it did cherish by chance, a root or two of good, the fragrance of which was sometimes perceptible amidst all this rank growth of poisonous weeds. A grown-up child he was – that was all.

The Doctor went on to describe an old country-seat, which stood near the village, and the ancient Hospital, which he had been telling about, and which was formerly the residence of the wicked man (a knight and a brave one, well known in the Lancastrian wars) who had founded the latter. It was a venerable old mansion, which a Saxon thane had begun to build more than a thousand years ago, the old English oak that he built into the frame being still visible in the ancient skeleton of its roof, sturdy and strong as if put up yesterday. And the descendants of the man that built it through the female line (for a Norman baron wedded the daughter and heiress of the Saxon,) dwelt there yet; and in each century, they had done something for the old Hall, – building a tower, adding a suite of rooms, strengthening what was already built, putting in a painted window, making it more spacious and convenient – till it seemed as if Time itself employed himself in thinking what could be done for the old house. As fast as any part decayed, it was renewed, with such simple art that it completed, as it were, and fitted itself to the old. So that it seemed as if the house had never been finished till just that thing was added. For many an age, the possessors went on adding strength to strength; digging out the moat to a greater depth; piercing the walls with holes for archers to shoot through, or building a turret to keep watch upon; but, at last, all necessity for such precautions passed away, and then they thought of convenient, and comfort, adding something of every garniture to these; and, by-and-by, they thought of beauty too; and in this time helped them with its weather-stains, and the ivy that grew over the walls and the grassy depths of the dried-up moat, and the abundant shade that grew up everywhere, where naked strength would have been ugly.

“One curious thing in the old house,” said the Doctor lowering his voice, but with a look of triumph, and that old scowl, too, at the children, “was that they build a secret chamber, a very secret one!”

“A secret chamber!” cried little Ned. “Who lived in it? A ghost?”

“There was often use for it,” said Doctor Grim: “hiding people who had fought on the losing side, or Catholic priests, or criminals, or perhaps – who knows? – enemies that they wanted to put out of the way, troublesome folks. Ah, it was often of use, that secret chamber, and is so still.”

Here, the Doctor paused, a long while, and leaned back in his chair, slowly puffing long whiffs from his pipe, looking up at the great spider-demon that hung over his head, and, as it seemed to the children, by the expression of his face, looking into the dim secret chamber, which he had spoken of, and which, by something in his mode of alluding to it; assumed such a weird, spectral aspect to their imaginations that they never wished to hear of it again. Coming back, at length, out of his reverie, – returning, perhaps, out of some weird, ghostly, secret chamber of his memory, of which the one in the old house was but the less horrible emblem – he resumed his tale. He said that, a long time ago, a war broke out in the old country, between King and Parliament. At that period, there were several brothers of the old family, (which had adhered to the Catholic religion), and these chose the side of the King, instead of that of the Puritan Parliament: all but one, whom the family hated, because he took the Parliament side; and became a soldier, and fought against his own brothers; and it was among them, that so inveterate was he, that he went on the scaffold, and was the very man who struck off the King’s head, and that his foot trod in the King’s blood, and that always afterwards, he made a bloody track wherever he went. And there was a legend that his brethren once caught this renegade and imprisoned him in his own birth-place

–“In the secret chamber?” interrupted Ned.

“No doubt!” said the Doctor, nodding, “though I never heard so.”

They imprisoned him, but he made his escape and fled, and, in the morning, his prison-place, wherever it was, was empty. But on the threshold of the door of the old manor-house, there was the print of a bloody footstep; and no trouble that the house-maids took, no rain of all the years that have passed since, no sunshine, has made it fade: no wear and trample of feet since passing over it, have availed to erase it.

“I have seen it myself,” quoth the Doctor, “and know this to be true!”

“Doctor Grim, now you are laughing at us,” said Ned, trying to look brave. But Elsie hid her face on the Doctor’s knee; there being something that affected the vivid little girl with peculiar horror in the idea of this red footstep always glistening on the door-step, and wetting, as she fancied, every innocent foot of child or grown people, that had since passed over it.

“It is true!” reiterated the grim Doctor; “for, man and boy, I have seen it a thousand times.”

He continued his family history, or tradition, or fantastic legend, whatever it might be; telling his young auditors that the Puritan, the renegade son of the family, was afterwards, by the contrivances of his brethren, sent to Virginia and sold as a bond slave; and how he had vanished from that quarter, and come to New England, where he was supposed to have left children. And, by and by, two elder brothers died, and this missing brother became the heir to the old estate and to a title; Then the family tried to track his bloody footstep, and sought it far and near; through the green country-paths and old streets of London, but in vain. Then they sent messengers to see if any traces of one stepping in blood could be found on the forest leaves of America; but still in vain. The idea nevertheless prevailed that he would come back, and it was said they keep a bedchamber ready for him yet in the old house. But, much as they pretended to regret the loss of him and his children, it would be a thing that would make them curse their stars were one of them to return now. For the children of a younger son were in possession of the old estate, and doing as much evil his their forefathers did; and if the true heir were to appear on the threshold, he would if he might but do it secretly, stain the whole door-step as red as the Bloody Footstep had stained one little portion of it.

“Do you think he will ever come back?” asked little Ned.

“Stranger things have happened, my little man,” said Doctor Grimshawe, “than that the posterity of this man should come back, and turn these usurpers out of his rightful inheritance. And sometimes, as I sit here smoking my pipe, and drinking my glass, and looking up at the cunning plot that the spider is weaving yonder above my head, and thinking of this fine old family, and some little matters that there have been between one of them and me – I fancy that it may be so! We shall see! Stranger things have happened.”

And Doctor Grimshawe drank off his tumbler, winking at little Ned, in a strange way, that seemed to be a kind of playfulness, but which did not affect the children pleasantly; insomuch that little Elsie put both her hands on Doctor Grim’s knees and begged him not to do so any more.

References

1Hawthorne, Nathanial, 1883, Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret: Boston, MA, James R. Osgood and Company, unk p.

2Hawthorne, Nathanial, 1890, Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret: Boston, MA, and New York, NY, Houghton Mifflin and Company, 368 p.

3Hoeltje, Hubert H., 1962, Inward Sky – the Mind and Heart of Nathaniel Hawthorne: Durham, NC, Duke Univ. Press, 379 p.

4“Hawthorne, Nathaniel” Encyclopædia Britannica, <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article?eu=40457> [Accessed May 30, 2002].

5Erlich, Gloria C., 1984, Family Themes and Hawthornes Fiction- the Tenacious Web: New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers Univ. Press, 217 p.

Webpage History

Webpage posted June 2002. Updated August 2004 with information on Grimshawe House and maps. Updated October 2004 with additions from 1890 edition (drawing and manuscript pages).