Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshaw

Clergyman, Author, Scholar

Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshawe was one of the more accomplished members of the Pendle Forest line of Grimshaws. He held two positions simultaneously in the Church of England and was author of several works, including two notable literary pieces- Memoirs of the Rev. Legh Richmond and The Works of William Cowper.

Contents

Position in the Descendant Chart of the Pendle Forest Grimshaws

Biography as Presented in The Preston Guardian Article of 1877

John Grimshaw, Father of Thomas Shuttleworth

Memoirs of the Rev. Legh Richmond

Family Connections with Legh Richmond

Thomas S. Grimshaw Also Wrote An Earnest Appeal to British Humanity, in Behalf of Hindoo Widows

Website Credits

Thanks to Hilary Tulloch for providing much of the biographical data on Thomas.

Position in the Descendant Chart of the Pendle Forest Grimshaws

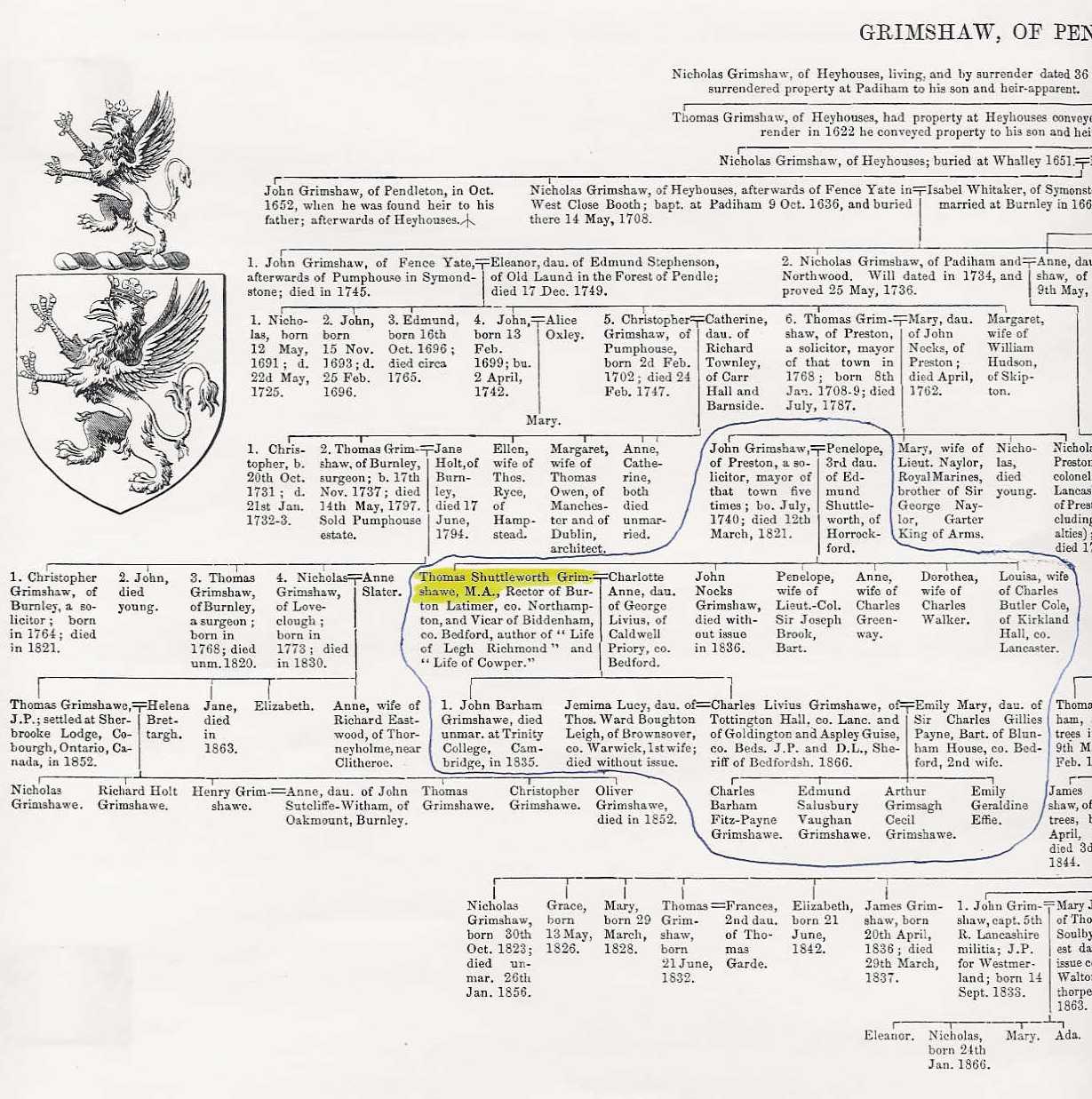

Thomas was a 7th-generation descendant of Nicholas Grimshaw, progenitor of the Pendle Forest line as presented in Whitaker1, 1872 (see companion webpage.) His parents were John and Penelope (Shuttleworth) Grimshaw, and he was the nephew of the well-known Nicholas Grimshaw, the mayor of Preston seven times. His position in the Pendle Forest descendant chart is shown below. He was born in about 1777 in Preston, Lancashire and died February 17, 1850 in Biddenham, Bedfordshire. He added the “e” to the Grimshaw surname for unknown reasons.

Location of Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshawe in the Pendle Forest descendant chart as presented in Whitaker1. The area enclosed in blue includes his parents, siblings and descendants.

Biography as Presented in The Preston Guardian Article of 1877

A very good biography of Thomas is presented in an article (one of a series of four on the Pendle Forest Grimshaws) published in The Preston Guardian2 on September 15, 1877. The relevant part of the article is presented below.

Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshawe, eldest son of John Grimshaw, Esq., and born in Preston in the year 1777, was a clergyman of considerable repute as an author and a scholar. He took the degree of M.A. at the University (I do not note whether it was Oxford or Cambridge), and entering holy orders, was beneficed at Biddenham, Co. Bedford, in the year 1808. Soon after he obtained, without resigning Biddenham, the rectory of Burton Latimer, Co. Northampton, Rev. Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshaw (he adopted the final “e” at the end of his surname) was a prominent member of what was called the “evangelical” section in the Church of England in the first half of the present century. His first essays in authorship were two or three pamphlets, of which the one which attracted the most notice was the following, which arose out of a dispute the writer had with the Bishop of Peterborough (Marsh), respecting the appointment of a curate:-.

“The Wrongs of the Clergy of the Diocese of Peterborough stated and illustrated. By the Rev. T.S. Grimshawe, M.A., Rector of Burton, Northamptonshire, and vicar of Biddenham, Bedfordshire.” London, Seeley. 1822. 8 vo

This pamphlet elicited a retort, entitled “A Refutation of Mr. Grimshawes Pamphlet,” &c., wherein it is mentioned that the curate nominated by Mr. Grimshawe in June, 1820, had been refused a license by Bishop Marsh on his refusal to submit to examination, upon which Mr. Grimshawe threatened to petition Parliament, &c. There was a very sharp dispute between Mr. Grimshawe and his diocesan on this matter. One of the Rev. T.S. Grimshawes pamphlets was printed in Preston, by T. Walker, entitled “An Exposition of the Principles of the Established Church, defined and explained according to the doctrine and principles of Dr. Calvin.” His larger publications were biographical, and were “Memoirs of the Rev. Legh Richmond, A.M.,: &c., 8 vo., pp. 662; and – “The Works of William Cowper. The Life and Letters by W. Hayley, Esq.; now first completed by the Introduction of Cowpers Private Correspondence. Edited by Rev. T.S. Grimshawe, M.A..” 8 vols. 1835-6.

Rev. Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshawe married Charlotte Anne, daughter of George Livius, Esq., of Caldwell Priory, Co. Bedford. (This lady survived him only a few months, and died June 28th, 1851.) He had issue two sons; the first, Mr. John Barham Grimshawe, died unmarried, at Trinity College, Cambridge, in the year 1835; the second, Charles Livius Grimshawe is again named hereafter. Rev. Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshawe had also several daughters, to whom the eldest, Augusta Emily, married, Feb. 22nd, 1848, the Rev. Bolingbroke Seymour, only son of Eyre Seymour, Esq., of Eyres Court, Galway; and the second daughter, Georgina, married, Oct. 30th, 1849, Legh Richmond, Esq., of Riversdale, Ashton-under-Lyne, the son, I believe, of the celebrated clergyman and author, Rev. Legh Richmond, whose memoir had been written by the Rev. T.S. Grimshawe. The latter clergyman died at Biddenham, Feb 17th, 1850. The subjoined obituary sketch of the character of the Rev. T.S. Grimshawe was published in The Gentlemans Magazine for May, 1850:- Feb. 17th, 1850 died at the Vicarage, Biddenham, Besds., in his 73rd year, the Rev. Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshawe, A.M., R.S.A., and M.B.S., Vicar of Biddenham (from 1808) , and late Rector of Burton Latimer, Northamptonshire (1809). This gentleman was a native of Preston, in Lancashire, and eldest son of the late John Grimshaw, Esq., many years senior alderman and several times Mayor of the Borough. A clergyman for many years distinguished by his pious zeal and activity in the Jewish and Church Missionary cause, he was the esteemed friend of the Rev. Charles Simeon, Edward Bickersteth, and Dr. Marsh. His characteristic interest in the conversion of the Jews impelled him, at the age of 60 years, to visit Palestine; and his subsequent addresses at the public meetings of his favourite societies derived a peculiar charm from his graphic, earnest recital of the incidents which accompanied his tour. He was universally loved, respected, and esteemed, not only by his own parishioners, amongst whom he laboured with unceasing zeal and affection; but by every one who

had the pleasure of being acquainted with him. But it was in the deep interest and untiring efforts manifested in behalf of those societies having for their object the propagation of the Gospel, and the spread of Evangelical truth, that Mr. Grimshawe, especially signalised himself. His favourite society was that for promoting Christianity among the Jews; and it is well known how he laboured for the peace of Israel, and for making known to that remarkable people those saving truths which were his stay and support through life. He was the author of (1) The Life of the Rev. Legh Richmond, (2) The Life and Works of William Cowper, Esq. In 8 volumes, 1835-6. This work was reviewed in our vol. III., p. 568, vol. IV., 339-345, 601-3, and its literary defects plainly pointed out; but though immediately followed by the more aspiring criticisms of Southey, it is said to be now in its third edition. Mr. Grimshawe undertook the task, regarding the object of his labours as The Poet of Christianity; and his edition has probably been supported by purchasers who have wished to view their favourite with the same partial and confiding admiration. The following notice of Mr. Grimshawe was read at the last meeting of the Syro-Egyptian Society:- At this society, we had to deplore the loss of one of our earliest patrons, John Barker, Esq., of Aleppo, formerly the Consul-General of Syria, and we have on this occasion to regret the decease of one of our learned members, the Rev. Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshawe, an accomplished scholar, who was respected by every person who had the honour and pleasure of his acquaintance. He was a gentleman of much literary attainment, of pure classic taste. Possessing much refinement of mind, he attached a high degree of importance to ancient history, and to those branches of knowledge, and of science, which proceed from those countries to which the attention of this society is more particularly directed. And a few years ago, with much spirit, at the age of about 70 years, he undertook a voyage to Egypt, and as ended the Nile to Thebes, and subsequently visited Jerusalem and the adjacent parts of the Holy Land; and he was accustomed to speak of the chronological and architectural wonders, and of the objects of natural history, which he had seen in his travels, with delight and enthusiasm. He was a man of great brilliancy of thought, and liberal in his opinions on matters relating to the ordinary subjects of life; and of enlightened views, of elegant manners, and most courteous in his demeanour. A large circle of relations and friends and neighbours now lament his decease.”The present representative of the branch of Grimshaws of Preston descending from John Grimshaw, Esq., of Preston, who died in 1821, is his grandson, the son of Rev. T.S. Grimshawe, described in the family record as Charles Livius Grimshawe, of Tottington Hall, Co. Lancaster, and of Goldington and Aspley Guise, Co. Bedford, J.P., and served the office of High Sheriff of Bedfordshire in 1866. That gentleman married, first, Jemima Lucy, daughter of Thomas Ward Broughton Leigh, of Brownsover, Co. Warwick (she died without issue), and, secondly, Emily Mary, daughter of Sir Charles Gillies Payne, Bart., of Blackburn House, Co., Bedford, by whom he has had issue, sons, Charles Barham Fitz Payne Grimshawe, Edmund Salusbury Payne Grimshawe, and Arthur Grimshargh Cecil Grimshawe; and a daughter, Emma Geraldine Effie.

Thomas, in addition to holding two clerical positions and authoring a number of books and other works, was also a scholar with strong interests in the Middle East.

John Grimshaw, Father of Thomas Shuttleworth

The article in the September 15 edition of The Preston Guardian2 also provided a good biography of Thomas father, John. Again, the relevant part is included below:

John Grimshaw, eldest son of Mr. Thomas Grimshaw of Preston, was born, as previously mentioned, at Preston, in the month of July, 1740. After his education, which probably was at the Grammar School in Preston, he entered his father’s office, being destined for the paternal profession of the law. On reaching manhood he commenced to practice at Preston as a solicitor on his own account. In the year 1762, at the age of 22, Mr. John Grimshaw served as one of the Bailiffs of the Borough of Preston at the Guild in that year. This was his first corporate appointment. In 1761 he took the prescribed oaths of allegiance and abjuration; and we find him again taking the oaths in 1763, and in 1768, at a session of the Borough Court, held Jan. 11th, at the house of William Dawson of Preston, innkeeper, the name of John Grimshaw occurs among those who took the new oaths of allegiance and abjuration imposed by the Government in 1766. John Grimshaw, gent., was elected a Councillor of the Borough on the 1st August, 1768, in the place of his father, who was at the same time elevated to the bench of Aldermen. At the Guild of 1782, Mr. John Grimshaw appears in high civic office as an Alderman of Preston; and shortly after the close of the Guild, on the termination of the term of office of Mr. Richard Atherton, Guild Mayor in that year, Alderman John Grimshaw was for the first time elected Mayor of Preston for the year 1782-3 He was then aged 42. From this date he was a chief Member of the Corporation during fifty years. After the lapse of six years, John Grimshaw, Esq., was appointed Mayor a second time in October, 1788. He fulfilled the office on this, as on the former occasion, with dignity and credit; and eleven years subsequently, in October 1799, Alderman John Grimshaw was for the third time elected Mayor of Preston. At the Guild of 1802, when his younger brother Nicholas was Mayor, John Grimshaw, Esq., officiated as one of the Stewards of the Guild. The fourth and last occasion of Alderman John Grimshaws fulfilment of the office of Mayor was in the year 1806-7. He completed his 67th year during his last term of the Mayoralty. He still continued to serve the office of Alderman for a good many years after that date; until, about the year 1820, having reached the age of eighty, John Grimshaw, Esq., resigned the office of Alderman and withdrew from the Civic Council. He sustained, before his resignation, the venerated position of Father of the Corporation, being considerably the oldest member of the Council, in which he had held a place without intermission during more than fifty years. Not long after his resignation, the Mayor and Council, in order to mark their high estimation of one who had served the borough so long and so well, subscribed a handsome sum, with which was purchased a valuable piece of plate, the presentation of which to Mr. John Grimshaw was made in January, 1821. This testimonial was inscribed as follows:-

“To John Grimshaw, Esquire, late Senior Alderman of the Corporation of Preston, and one of his Majestys Justices of the Peace for that Borough; who, for a long series of years, supported the rights and interests of the body corporate, and promoted the peace and welfare of the borough in general, with equal ability, integrity, and zeal, this Cup is presented as a token of gratitude for his public services, and of esteem and regard for his private character, by the Mayor, Aldermen, and capital Burgesses of the Borough, in Common Council assembled.”

The veteran Burgess did not long survive the receipt of this tribute by the Mayor and Council to his worth and his service to the town. John Grimshaw died in his 81st year, on the 12th of March, 1821.

Mr. John Grimshaw married Penelope, daughter of Mr. Edmund Shuttleworth of Horrocksford, near Clitheroe. By her he had issue two sons and four daughters. His first son was born in 1777, and was christened Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshawe, taking for his second name the maternal surname. Of this son a further notice is given below. The second son was named John Nock Grimshaw, the second of his names being the surname of his grandmother, Mary Nock. Mr. John Nock Grimshaw died, it is stated, without issue, in the year 1836. He held the office of Bailiff of the borough in the same year (1806) in which his father was last time Mayor. The daughters of John Grimshaw, Esq., were, Penelope, wife of Lieut. Col. Sir Joseph Brook, Bart.; Anne, first wife of Charles Greenway, Esq., of Ardwick and Darwen. (Her obituary occurs:- “1827. April 26. Ann, wife of Charles Greenway, Esq., and daughter of the late John Grimshaw Esq., of Preston, aged 39.”) Dorothea, third daughter, married Mr. Charles Walker; and the fourth daughter, Loiusa Grimshawe, became the wife of Charles Butler Cole of Kirkland, Esq.

John came from a politically active family Grimshaws in the Preston area. He not only served as mayor and held other political offices himself, but he was the older brother of Nicholas, who became even more politically prominent. Nicholas served as mayor seven times, including two Guild mayoralties, and is the subject of a companion webpage.

Memoirs of the Rev. Legh Richmond

The first major literary work of Thomas was apparently his Memoirs of the Rev. Legh Richmond3, which was published in 1834. The page facing the title page is an engraving of the Rev. Richmond and is shown below. Click here for the entire book.

Image of the Rev. Legh Richmond’s engraved portrait from T.S. Grimshawe’s Memoirs of the Rev. Legh Richmond3

A sample of Thomas’ writing, comprising Chapter 2 of this work, is shown below.

CHAPTER II.

His entrance on his professional duties – Remarkable change in his views and conduct, and the incident that occasioned it – Reflections on the foregoing event.

Mr. RICHMOND appears to have entered on the ministry with the desire and aim of discharging its important duties in a conscientious manner: and he manifested such propriety of conduct in his moral deportment, and in the general duties of his new charge, as to procure for him the character of a highly respectable and useful young clergyman. A few months, however, after his residence at Brading, a most important revolution took place in his views and sentiments, which produced a striking and prominent change in the manner and matter of his preaching, as well as in the general tenor and conduct of his life. This change was not a conversion from immorality to morality; for he was strictly moral, in the usual acceptation of the term. Neither was it a conversion from orthodoxy in name and profession, to orthodoxy in its spirit, tendency, and influence. But before we indulge in any further remarks, it is necessary to record the particulars of the occurrence to which we have alluded. Shortly after he had entered on his curacies, one of his college friends who was on the eve of taking holy orders, had received from a near relative Mr. Wilberforce’s ‘Practical View of Christianity.” This thoughtless candidate for the momentous charge of the Christian ministry forwarded the book to Mr. Richmond, requesting him to give it a perusal, and to inform him what he must say respecting its contents. In compliance with this request, he began to read the book, and found himself so deeply interested in its contents, that the volume was not laid down until the perusal of it was completed. The night was spent in reading and reflecting upon the important truths contained in this valuable and impressive work. In the course of his employment, the soul of the reader was penetrated to its inmost recesses; and the effect produced in innumerable instances by the book of God, was in this case accomplished by means of a human composition. From that period his mind received a powerful impulse, and was no longer able to rest under its former impressions. A change was effected in his views of divine truth, as decided as it was influential. He was no longer satisfied with the creed of the speculatist – he felt a conviction of his own state as a guilty and condemned sinner, and under that conviction, he sought mercy at the cross of the Saviour. There arose in his mind a solemn consciousness that, however outwardly moral and apparently irreproachable his conduct might appear to men; yet within, there was wanting that entire surrender of the heart, that ascendancy of God in the soul, and that devoted ness of life and conduct, which distinguishes morality from holiness; an assent to divine truth, from its cordial reception into the heart; and the external profession of religion, from its inward and transforming power. The impressions awakened were therefore followed by a transfer of his time, his talents, and his affections, to the service of his God and Saviour, and to the spiritual welfare of the flock committed to his care. But while his mind was undergoing this inward process, it is necessary to state how laborious he was in his search after truth. The Bible became the frequent and earnest subject of his examination, prayer, and meditation. His object was fontes haurire sacros– to explore truth at its fountain head, or, in the emphatic language of scripture, to “draw water out of the wells of salvation.” From the study of the Bible, he proceeded to a minute examination of the writings of the Reformers, which, by a singular coincidence, came into his possession shortly after this period; and having from these various sources acquired increasing certainty as to the correctness of his recent convictions, and stability in holding them, he found – what the sincere and conscientious inquirer will always find – the Truth; and his heart being interested, he learnt truth through the heart, and believed it, because he felt it.

His own account of the effect produced on his mind by the perusal of Mr. Wilberforce’s book, will excite the interest of the reader. Speaking of his son Wilberforce, he remarks: —

‘He was baptized by the name of Wilberforce, in consequence of my personal friendship with that individual wit whose name long has been, and ever will be, allied to all that is able, amiable, and truly Christian. That gentleman had already accepted the office of sponsor to one of my daughters; but the subsequent birth of this boy afforded me the additional satisfaction of more familiarly associating his name with that of my family. But it was not the tie of ordinary friendship, nor the veneration which, in common with multitudes, I felt for the name of Wilberforce, which induced me to give that name to my child; there had, for many years past, subsisted a tie between myself and that much-loved friend, of a higher and more sacred character than any other which earth can afford. I feel it to be a debt. of gratitude, which I owe to God and to man, to make this affecting opportunity of stating, that to the unsought and unexpected introduction to Mr. Wilberforce’s book on ‘Practical Christianity’ I owe, through God’s mercy, the first sacred impression which I ever received, as to the spiritual nature of the gospel system, the vital character of personal religion, the corruption of the human heart, and the way of salvation by Jesus Chris. As a young minister, recently ordained, and entrusted with the charge of two parishes in the Isle of Wight, I had commenced my labours too much in the spirit of the world, and founded my public instructions on the erroneous notions which prevailed amongst my academical and literary associates. The scriptural principles stated in the ‘Practical View,’ convinced me of my error; error; led me to the study ,of the scriptures with an earnestness to which I had hitherto been a stranger; humbled my heart, and brought me to seek the love and blessing of that Saviour, who alone can afford a peace which the world cannot give. Through the study of this book, I was induced to examine the writings of tile British and Foreign Reformers. I saw the coincidence of their doctrines with those of the scriptures, and those which the word of God taught me to be essential to the welfare of myself and my flock. I know too well what has passed within my heart, for now a long period of time, not to feel and to confess, that to this incident I was as indebted, originally, for those solid views of Christianity on which I rest my hope for time and eternity. May I not, then, call the honoured author of that book my spiritual father? And if my spiritual father, therefore my best earthly friend. The wish to connect his name with my own was natural and justifiable. It was a lasting memorial of the most important transaction of my life; it still lives amidst the tenderness of present emotions, as a signal of endearment and gratitude; and I trust its character is imperishable.’

Though Mr. Richmond’s mind and heart were experiencing the remarkable change which has been recorded, it is necessary to state that the regularity and decorum with which be was previously discharging his duties, far exceeded those of many other ministers. If then, notwithstanding these exertions, he was still conscious how much he fell short of the standard of ministerial faithfulness and zeal, and the requirements of personal holiness; may we not ask, what ought to be the convictions of those who evince a far less degree of earnestness, where the claims are precisely the same, and the obligations to fulfil them are equally binding? If he felt the need within of a more operative principle of divine grace, as the only genuine source of inward and external holiness, what must be their state who, with greater deficiencies, experience no conflict of the mind, no secret misgivings of the conscience? If, in his ardent inquiry after truth, he meditated over the sacred page, and explored the voluminous writings of the reformers, what is their responsibility who rest in a system, without an endeavour to ascertain its correctness; who give to the world the hours sacred to prayer and study; or who appropriate their time to objects, which, however praiseworthy in themselves, are not sufficiently identified with their profession, nor calculated to promote their advancement in grace and holiness?

But we should pursue this subject further, and demand, if conversion, or a change of heart and life, be necessary in all men, because all naturally partake of the principle of inward corruption, how much rnore is it necessary to him who officiates in holy things; and who, by the titles which designate his character and office, is supposed to contract engagements of the highest and most sacred import!

And yet the very nature and necessity of conversion is questioned by some, in opposition to the most express declarations of Holy Writ; thus proving their own need, at least, of that conversion: the possibility of which they so heedlessly dispute. A distinguished and excellent prelate, in our own day, has merited well of the Christian public, by inviting attention to this subject. In the diocese of St. Davids, a price was offered for the best essay on the signs of conversion and unconversion in ministers of the Established Church.

This was at once recognizing the doctrine, as well as the necessity of conversion. It drew the line of demarcation between true piety, and that which bears only the external garb. It admitted the conversion of some, it doubted the conversion of all: and, by instituting an inquiry into the signs and evidences by which the distinction is to be known, it held out a beacon to discriminate the true and faithful pastor from the bold and unauthorised intruder. Let it be remembered too, that this doctrine is avowedly maintained, and the belief and experience of its truth no less avowedly professed, by every candidate, in the form and ceremony prescribed by our own church for ordination; – that on this occasion he is solemnly asked, whether he trusts that he is inwardly moved by the Holy Ghost, to take upon himself the sacred office? To which he deliberately answers, I trust so. And that, if terms be significant of things, and professions mean what they are supposed to imply, this call of the Holy Spirit denotes a series of qualifications, of which the real conversion of the heart is the primary and most indispensable. It is on the authority of this declaration, and the supposed sincerity of its avowal, that He is permitted to officiate at her altars, and that the dispensation of the Gospel is committed to his hands; and therefore the absence of this qualification is not merely a fraud, and an act of perjury, aggravated by the solemnity of the occasion, and by the bold profanation of holy things; but a crime of a still higher magnitude. Souls are betrayed, for every one of which he must render an account to Him who has authoritatively proclaimed, “their blood will I require at thine hand.”

Another very important lesson to be learnt from the preceding narrative, is the necessity of discriminating morality from religion. The principal error in Mr. Richmonds former views consisted in this, – that they were deficient in the grand characteristic features of the gospel. Not that he actually denied a single doctrine which the gospel inculcates; but his conceptions were far from being definite, clear, and comprehensive. They wanted the elevation and spirituality of the Christian system. They were founded more on the standard of morality, than the principles of the gospel; and therefore were defective as it respects the motive and end of all human actions, the two essential properties which renders an action acceptable in the sight of a holy God. A heathen may be moral, a Christian must be more: for though true religion will always comprise morality, yet a degree of external morality may exist without religion. There was a confusion, also, in his notion of faith and works, and of the respective offices and design of the law and of the gospel. The Saviour was not sufficiently exalted, nor the sinner humbled; and there was wanting the baptism of the Holy Ghost and of fire. Matt. iii. 11. His sermons, partaking of the same character, were distinguished indeed by solidity of remark, force of expression, strong appeals to the conscience, and a real and commendable zeal for the interests of morality; but they went no further. As regarded the great end of the Christian ministry – the conversion of immortal souls – they were powerless; for moral sermons can produce nothing but moral effects; and it is the gospel alone that is “mighty through God to the pulling down of the strong holds of sin; and bringing into captivity every thought to the obedience of Christ.” 2 Cor. x. 4, 5.

There was, indeed, an external reformation produced among his people; but the renovation of the heart, the communion of the soul with God, the inward joy and peace of the gospel, and the hope full of life and of immortality – these were not experienced and felt, because they were not preached; and they were not preached, because they were not adequately understood by the preacher. And is there no ground for apprehension that the same deficiency still exist amongst us to a considerable extent? Are the peculiar doctrines of Christianity commonly brought forward with sufficient clearness, fidelity, and zeal? Are the corruption and lost estate of man, the mercy of God in Christ, the necessity of a living faith in the Saviour, the office of the Holy Spirit in his enlightening, converting, and sanctifying influences, p are these grand themes of the Christian ministry urged with the prominence that their incalculable importance demands? Deficiencies in points like these are serious impediments to the growth of true religion, and cannot be too sedulously reproved by those who are the constituted guardians of sound doctrine. For with the mere moralist, the grandeur of the Christian dispensation – the divine love so conspicuous in the whole of its stupendous plan – the beauty, order, and symmetry of its several parts, are all reduced to the rank and level of a secondary and subordinate scheme. Christ is not the centre of the system, but rather occupies the extreme point; and is brought in as a last expedient to cover the nakedness and insufficiency of our own works. The moralist, according to his own creed, does all that he can, and then – looks to his Redeemer to perform the rest. On the other hand, where the moralist ends, the believer begins. With him, every work is begun, continued, and ended in God. He draws from above every motive for his obedience, every promise for his encouragement, and strength to subdue all his corruptions. Christ is the sun that illuminates his moral horizon, the living waters to refresh his thirst, the heavenly manna by which he is fed, “the first and the last, the beginning and the ending, the Alpha and Omega, the all and in all.” He is the prophet, by whose wisdom he is taught; the Priest, by whose sacrifice he is pardoned; the King, by whose authority he is swayed; and the Shepherd, on whose tender care he reposes all his wants. What, then, is the remedy for the defects to which we have alluded, and for the fatal consequences resulting from them? The knowledge of the Gospel; and the full, free, and faithful declaration of its truths. There must be its tidings on the lips, its grace in the heart, and its holiness in the life of the preacher. Such was the case in the instance of Mr. Richmond after the change above recorded; and crowded auditories, and inquiring people, and numerous conversions were the happy result. And such will ever be the case where the gospel is faithfully preached. The same causes will always produce the same effects. The blind will receive their sight, and the lame walk, and the deaf hear, and the spiritually dead be raised up to life eternal.

Family Connections with Legh Richmond

Thomas’ connection with Rev. Richmond was not only literary and religious, but also familial, as noted in the article from The Preston Guardian (see above.) Richmond4 (p. 263, 275) notes that Legh Serle Richmond, 10th child of Rev. Legh and Mary (Chambers) Richmond, married Georgianna Grimshawe as his second wife (the first was Cecelia Cheyne.) Georgianna was the daughter of T.S. Grimshawe.

The Works of William Cowper4

The second major literary work of Thomas Shuttleworth Grimshawe was The Works of William Cowper, which was published only a year after Memoirs of the Rev. Legh Richmond, in 1835. Most of the volumes have beautiful engravings opposite the title pages showing various people and places that were significant in Cowper’s life. As examples of this artwork, the three figures below show, respectively, a portrait of Cowper, his mother, and his village home in Weston.

Image of the engraving of Cowper’s portrait, from volume VI of T.S. Grimshawe’s The Works of William Cowper4

Image of the engraving of Cowper’s mother, from volume VII of T.S. Grimshawe’s The Works of William Cowper4

Image of the engraving of Cowper’s home at Weston, from volume II of T.S. Grimshawe’s The Works of William Cowper4

A sample of Thomas’ writing in The Works of William Cowper4 is taken from the first twelve pages of volume I and is shown below:

THE family of Cowper appears to have held, for several centuries, a respectable rank among the merchants and gentry of England. We learn from the life of the first Earl Cowper, in the Biographia Britannica, that his ancestors were inhabitants of Sussex in the reign of Edward the Fourth. The name is found repeatedly among the sheriffs of London, and William Cowper, who resided as a country gentleman in Kent; was created a baronet by King Charles the First, in 1641. But the family rose to higher distinction in the beginning of the last century, by the remarkable circumstance of producing two brothers who both obtained a seat in the House of Peers by their eminence in the profession of the law. William, the elder, became Lord High Chancellor in 1707. Spencer Cowper, the younger, was appointed Chief Justice of Chester in 1717, and afterwards a Judge in the Court of Common Pleas, being permitted by the particular favour of the king to hold those two offices to the end of his life. He died in Lincoln’s Inn, on the 10th of December, 1728, and has higher the higher claim to our notice as the immediate ancestor of the poet. By his first wife, Judith Pennington (whose exemplary character is still revered by her descendants) Judge Cowper left several children; among them a daughter, Judith, who at the age of eighteen discovered a striking talent for poetry, in the praise of her contemporary poets Pope and Hughes. This lady, the wife of Colonel Madan, transmitted her own poetical and devout spirit to her daughter Frances Maria, who was married to her cousin Major Cowper; the amiable character of Maria will unfold itself in the course of this work, as the friend and correspondent of her more eminent relation, the second grandchild of the Judge, destined to honour the name of Cowper, by displaying, -with peculiar purity and fervour, the double enthusiasm of poetry and devotion. The father of the subject of the following pages was John Cowper, the Judge’s second son, who took his degrees in divinity, was chaplain to King George, the Second, and resided at his Rectory of Great Berkhamstead, in Hertfordshire, the scene of the poet’s infancy, which he has thus commemorated in a singularly beautiful and pathetic composition on the portrait of his mother.

Where once we dwelt our name is heard no more,

Children not thine have trod my nursery floor, –

And where the gard’ner Robin, day by day,

Drew me to school along the public way,

Delighted with my bauble coach, and wrapt

In scarlet mantle warm, and velvet-capt.

Tis now become a history little known,

That once we call’d the past’ral house our own.

Short-liv’d possession! but the record fair

That memory keeps of all thy kindness there,

Still outlives many a storm, that has effac’d

A thousand other themes less deeply traced.

Thy nightly visits to my chamber made.

That thou might’st know me safe and warmly laid;

Thy morning bounties ere I left my home

The biscuit or confectionary plum;

The fragrant waters on my cheeks bestowed

By thy own hand, till fresh they shone and glow’d;

All this, and more endearing still than all,

Thy constant flow of love, that knew no fall;

Ne’er roughen’d by those cataracts and breaks.

That humour interpos’d too often makes.

All this, still legible, in memory’s page,

And still to be so to my latest age,

Adds joy to duty, makes me glad to pay

Such honours to thee as my numbers may.

The parent, whose merits are so feelingly recorded by the filial tenderness of the poet, was Ann, daughter of Roger Donne, Esq., of Ludham Hall, in Norfolk. This lady, whose family is said to have been originally from Wales, was married in the bloom of youth to Dr. Cowper: after giving birth to several children, who died in their infancy, and leaving two sons, William, the immediate subject of this memorial, born at Berkhamstead on 26th of November, 1731, and John, (whose accomplishments and pious death will be described in the course of this compilation,) she died in childbed, at the early age of thirty-four, in 1737. Those who delight in contemplating the best affections of our nature will ever admire the tender sensibility with which the poet has acknowledged his obligations to this amiable mother, in a poem composed more than fifty years after her decease. Readers of this description may find a pleasure in observing how the praise so liberally bestowed on this tender parent, at so late a period, is confirmed (if praise unquestionable may be said to receive confirmation) by another poetical record of her merit, which the hand of affinity and affection bestowed upon her tomb – a record written at a time when the poet, who was destined to prove, in his advanced life, her most powerful eulogist, had hardly begun to shew the dawn of that genius which, after many years of silent affliction, rose like a star emerging from tempestuous darkness.

The monument of Mrs. Cowper, erected by her husband in the chancel of St. Peter’s church at Berkhamstead, contains the following verses, composed by a young lady, her niece, the late lady Walsingham.

Here lies, in early years bereft of life,

The best of mothers and the kindest wife.

Who neither knew nor practis’d any art,

Secure in all she wish’d, her husband’s heart,

Her love to him, still prevalent in death,

Pray’d Heaven to bless him with her latest breath.

Still was she studious never to offend,

And glad of an occasion to commend:

With ease would pardon injuries receiv’d,

Nor e’er was cheerful when another griev’d;

Despising state, with her own lot content,

Enjoy’d the comforts of a life well spent;

Resign’d when Heaven demanded back her breath,

Her mind heroic ‘midst the pangs of death,

Whoe’er thou art that dost this tomb draw near,

O stay awhile, and shed a friendly tear;

These lines, tho’ weak, are as herself sincere.

The truth and tenderness of this epitaph will more than compensate with every candid reader the imperfection ascribed to it by its young and modest author. To have lost a parent of a character so virtuous and endearing, at an early period of his childhood, was the prime misfortune of Cowper, and what contributed perhaps in the highest degree to the dark colouring of his subsequent life. The influence of a good mother on the first years of her children, whether nature has given them peculiar strength or peculiar delicacy of frame, is equally inestimable. It is the prerogative and the felicity of such a mother to temper the arrogance of the strong and to dissipate the timidity of the tender. The infancy of Cowper was delicate in no common degree, and his constitution discovered at a very early season that morbid tendency to diffidence, to melancholy, and despair, which darkened as he advanced in years into periodical fits of the most deplorable depression.

The period having arrived for commencing his education he was sent to a reputable school at Market-street, in Hertfordshire under the care of Dr. Pitman, and it is probable that he was removed from it in consequence of an ocular complaint. From a circumstance which he relates of himself at that period, in a letter written in 1792, he seems to have been in danger of resembling Milton in the misfortune of blindness, as he resembled him, more happily, in the fervency of a devout and poetical spirit.

“I have been all my. life, says Cowper, subject to inflammations of the eye, and in my boyish days had specks on both, that threatened to cover them. My father, alarmed for the consequences, sent me to a female oculist of great renown at that time, in whose house I abode two years, but to no good purpose. From her I went to Westminster school, where, at the age of fourteen, the small-pox seized me, and proved the better oculist of the two, for it delivered me from them all: not however from great liableness to inflammation, to which I am in a degree still subject, though much less than formerly, since I have been constant in the use of a hot footbath every night, the last thing before going to rest.”

It appears a strange process in education, to send a tender child, from a long residence in the house of a female, oculist, immediately into all the hardships attendant on a public school. But the mother of Cowper was dead, and fathers, however excellent, are, in general, utterly incompetent to the management of their young and tender offspring. The little Cowper was sent to his first school in the year of his mother’s death, and how ill-suited the scene was to his peculiar character is evident from the description of his sensations in that season of life, which is often, very erroneously, extolled as the happiest period of human existence. He has been frequently heard to lament the persecution he suffered in his childish years, from the cruelty of his school-fellows, in the two scenes of his education. His own forcible expressions represented him at Westminster as not daring to raise his eye above the shoe-buckle of the elder boys, who were too apt to tyrannize over his gentle spirit. The acuteness of his feelings in his childhood, rendered those important years (which might have produced, under tender cultivation, a series of lively enjoyments) mournful periods of increasing timidity and depression. In the most cheerful hours of his advanced life, he could never advert to this season without: shuddering at the recollection of its wretchedness. Yet to this perhaps the world is indebted for the pathetic and moral eloquence of those forcible admonitions to parents, which give interest and beauty to his admirable poem on public schools. Poets may be said to realize, in some measure, the poetical idea of the nightingale’s singing with a thorn at her breast, as their most exquisite songs have often originated in the acuteness of their personal sufferings. Of this obvious truth, the poem just mentioned is a very memorable example, and, if any readers have thought the poet too severe in his strictures on that system of education, to which we owe some of the most accomplished characters that ever gave celebrity to a civilized nation, such readers will be candidly reconciled to that moral severity of reproof, in re-collecting that it flowed from severe personal experience, united to the purest spirit of philanthropy and patriotism.

The relative merits of public and private education is a question that has long-agitated the world. Each has its partizans, its advantages, and defects; and, like all general principles, its application must greatly depend on the circumstances of rank, future destination, and the peculiarities of character and temper. For the full development of the powers and faculties of the mind – for the acquisition of the various qualifications that fit men to sustain with brilliancy and distinction the duties of active life, whether in the cabinet, the senate, or the forum – for scenes of busy enterprize, where knowledge of the world and the growth of manly spirit, seem indispensable; in all such cases, we are disposed to believe, that the palm must be assigned to public education.

But, on the other hand, if we reflect that brilliancy is oftentimes a flame which consumes its object, that knowledge of the world is, for the most part, but a knowledge of the, evil that is in the world; and that early habits of extravagance and vice, which are ruinous in, their results, are not unfrequently contracted at public schools; if to these facts we add that man is a candidate for immortality, and that “life,” (as Sir William Temple observes,) “is but the parenthesis of eternity,” it then becomes a question of solemn import, whether integrity and principle do not find a soil more congenial for their growth in the shade and retirement of private education? The one is an advancement for time, the other for eternity. The former affords facilities for making men great, but often at the expense of happiness and conscience. The latter diminishes the temptations to vice, and, while it affords a field for useful and honourable exertion, augments the means of being wise and holy.

We leave the reader to decide tile grand problem for himself. That he may be enabled to form a right estimate, we would urge him to suffer time and eternity to pass in solemn and -deliberate review before him.

That the public school was a scene by no means adapted to the sensitive mind of Cowper is evident. Nor can we avoid cherishing the apprehension that his spirit, naturally morbid, experienced a fatal inroad from that period. He nevertheless acquired the reputation of scholarship, with the advantage of being known and esteemed by some of the aspiring characters of his own age, who subsequently -became distinguished in the great arena of public life.

With these acquisitions, he left Westminster at the age of eighteen, in 1749; and, as if destiny had determined that all his early situations in life should be peculiarly irksome to his delicate feelings, and tend rather to promote than to counteract his constitutional tendency to melancholy, he was removed from a public school to the office of an attorney; He resided three years in the house of a Mr. Chapman, to whom he was engaged by articles for that time. Here he was placed for the study of a profession, which nature seemed resolved that he never should practise.

The Law is a kind of soldiership, and, like the profession of arms, it may be said to require for the constitution of its heroes

” A frame of adamant, a soul of fire.”

The soul of Cowper had indeed-its fire, but fire so refined and etherial, that it could not be expected to shine in the gross atmosphere of worldly contention. Perhaps there never existed a mortal, who possessing, with a good person, intellectual powers naturally strong and highly cultivated, was so utterly unfit to encounter the bustle and perplexities of public life. But the extreme modesty and shyness of his nature, which disqualified him for scenes of business and ambition, endeared him inexpressibly to those who had opportunities to enjoy his society, and discernment to appreciate the ripening excellencies of his character.

Reserved as he was, to an extraordinary and painful degree, his heart and mind were yet admirably fashioned by nature for all the refined intercourse and confidential enjoyment both of friendship and love: but, though apparently formed to possess and to communicate an extraordinary portion of moral felicity, the incidents of his life were such, that, conspiring with the peculiarities of his nature, they- rendered him, at different times, the victim of sorrow. The variety and depth of his sufferings in early life, from extreme tenderness of feeling, are very forcibly displayed in the following verses, which formed part of a letter to one of his female relatives, at the time they were composed. The letter has perished, and the verses owe their preservation to the affectionate memory of the lady to whom they were addressed.

Doom’d, as I am. in solitude to waste

The present moments, and regret the past;

Depriv’d of every joy I valued most.

My friend torn from me, and my mistress lost;

Call not this gloom I wear, this anxious mien.

The dull effect or humour, or of spleen!

Still, still, I mourn, with each returning day,

Him* snatch’d by fate in early youth away.

And her – thro’ tedious years of doubt and pain,

Fix’d in her choice, and faithful – but in vain!

O prone to pity, generous, and sincere,

Whose eye ne’er yet refus’d the wretch a tear;

Whose heart the real claim of friendship knows,

Nor thinks a lover’s are but fancied woes;

See me – ere yet my destin’d course half done,

Cast forth a wand’rer on a world unknown!

See me neglected on the world’s rude coast.

Each dear companion or my voyage lost!

Nor ask why clouds of sorrow shade my brow,

And ready tears wait only leave to flow!

Why all that soothes a heart from anguish free,

All that delights the happy – palls with me!

*Sir William Russel, the favourite friend of the young poet.

Having concluded the term of his engagement with the solicitor, he settled himself in chambers in the Inner Temple, as a regular student of law; but, although he resided there till the age of thirty-three, he rambled (according to his own colloquial account of his early years) from the thorny road of his austere patroness, Jurisprudence, into the primrose paths of literature and poetry. Even here his native diffidence confined him to social and subordinate exertions: he wrote and printed both verse and prose, as the concealed assistant of less diffident authors. During this period, he cultivated the friendship of some very literary characters, who had been his schoolfellows at Westminster, particularly Colman, Bonnel Thornton, and Lloyd. His regard for the two first induced him to contribute to their periodical publication, entitled the Connoisseur, three excellent papers, which afford satisfactory evidence that Cowper had such talents for this pleasant and useful species of composition, as might have rendered him a worthy associate, in such labours, with Addison himself, whose graceful powers have never been surpassed in that province of literature, which may be considered as peculiarly his own.

Thomas S. Grimshaw Also Wrote An Earnest Appeal to British Humanity, in Behalf of Hindoo Widows

Thomas wrote another, shorter tract6 on behalf of Hindu widows in the early 1800s. The full title is as follows:

An Earnest Appeal to British Humanity, in Behalf of Hindoo Widows: in Which the Abolition of the Barbarous Rite of Burning Alive Is Proved To Be Both Safe and Practicable.

The chapter titles of this work are shown below. Click here for the full text.

CHAPTER I. Burning of Hindoo Widows – Extent of the Practice – Prevalence near the Seat of Supreme Government – Atrociousness of the Rite – Violation of Human and Divine Laws – Regulations adopted to restrain it – their insufficiency – Necessity of ulterior measures.

CHAPTER II. Objections to a more efficient mode of proceeding, considered – Practice, whether founded on Law – Amenable to the Civil Power – How far voluntary – Authority of a Treaty, when subversive of Justice, Morality, and Religion – Testimony of Locke,

CHAPTER III. Alleged Danger of Interference – Vellore Meeting – Argument of Policy – Limitations to its use – How far uniformly adhered to.

CHAPTER IV. Innovations, relating to – Collection of Tribute – Tenure of Land – Administration of Law – Treatment of Native Princes – Popular Worship – Inviolability of Bramins.

CHAPTER V. Precedents for Interference – Infanticide – Edict of Marquis Wellesley – Successful Efforts of Governor Duncan and Colonel Walker – Jagee Tribes- Regulation against Widows burying alive – Prohibition of burning alive, by the Mohammedan, Portuguese, Dutch, Danish, and French Governments.

CHAPTER VI. Testimonies as to the Practicability of abolishing the Rite – Opposite Views; by what characterized -The Practicability, established – Successful Interference of Local Authorities.

CHAPTER VII. Appeal to Constituted Authorities – Necessity of Penal Enactments – Awful Responsibility incurred – On whom it attaches – Argument of Policy finally considered – Duty and real Policy of Great Britain.

References

1Whitaker, Thomas Dunham, 1872, An History of the Original Parish of Whalley, and Honor of Clitheroe (Revised and enlarged by John G. Nichols and Ponsonby A. Lyons): London, George Routledge and Sons, 4th Edition; v. I, 362 p.; v. II, 622 p. Earlier editions were published in 1800, 1806, and 1825.

2Author Unknown, 1877, Sketches in Local History: Memorials of Old Lancashire Families the Grimshaws of Pendle Forest and of Preston (Third Paper): Preston, Lancashire, England, The Preston Guardian, September 15, 1877, 2nd Sheet, p. 1.

3Grimshawe, The Rev. T.S., 1834, A Memoir of the Rev. Legh Richmond: London, R.B. Seeley and W. Burnside, 451 p.

4Richmond, Henry I., Richmond Family Records, v. III, The Richmonds of Wiltshire: London, Adland & Son, 327 p.

5Grimshawe, The Rev. T.S., 1835, The Works of William Cowper: London, Saunders and Otley, in 8 volumes (vol. I, 334 p.; vol. II, 340 p.; vol. III, 319 p.; vol. IV, 354 p.; vol. V, 413 p.; vol. VI, 281 p.; vol. VII, 359 p.; vol. VIII, 431 p.)

6Grimshawe, The Rev. T.S., 1825, An Earnest Appeal to British Humanity, in Behalf of Hindoo Widows: in Which the Abolition of the Barbarous Rite of Burning Alive Is Proved To Be Both Safe and Practicable: London, Hatchard & Son and Seeley & Son, 28 p.

Webpage History

Webpage posted March 2001. Banner replaced April 2011. Updated April 2013 with addition of “An Earnest Appeal to British Humanity, in Behalf of Hindoo Widows: in Which the Abolition of the Barbarous Rite of Burning Alive Is Proved To Be Both Safe and Practicable” – and several updates in format.