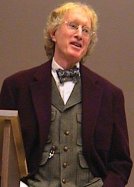

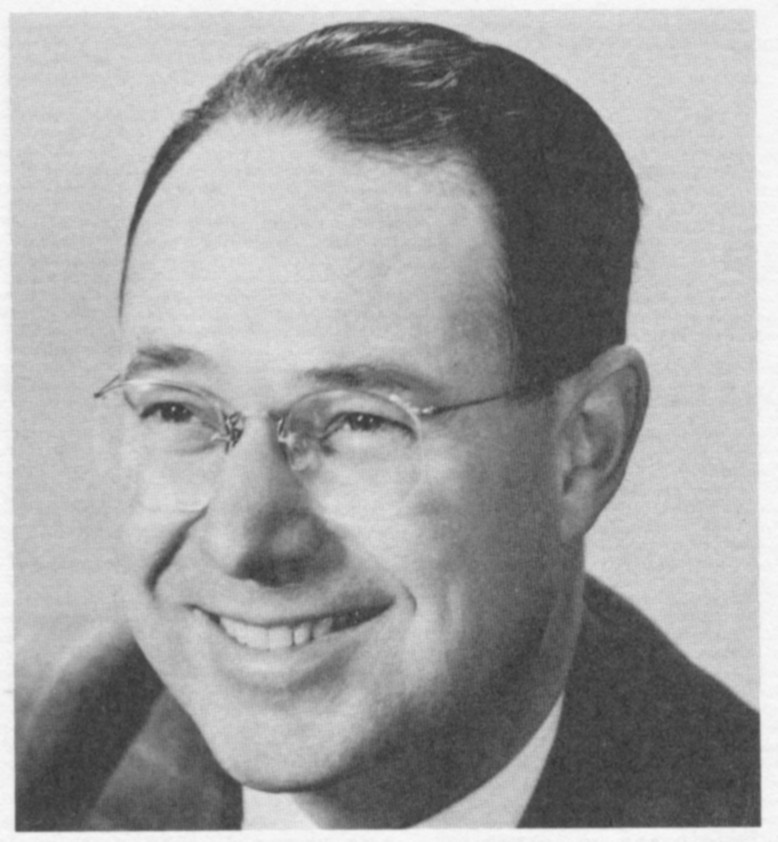

Austin Grimshaw, Dean of the University of Washington School of Business

Austin Grimshaw

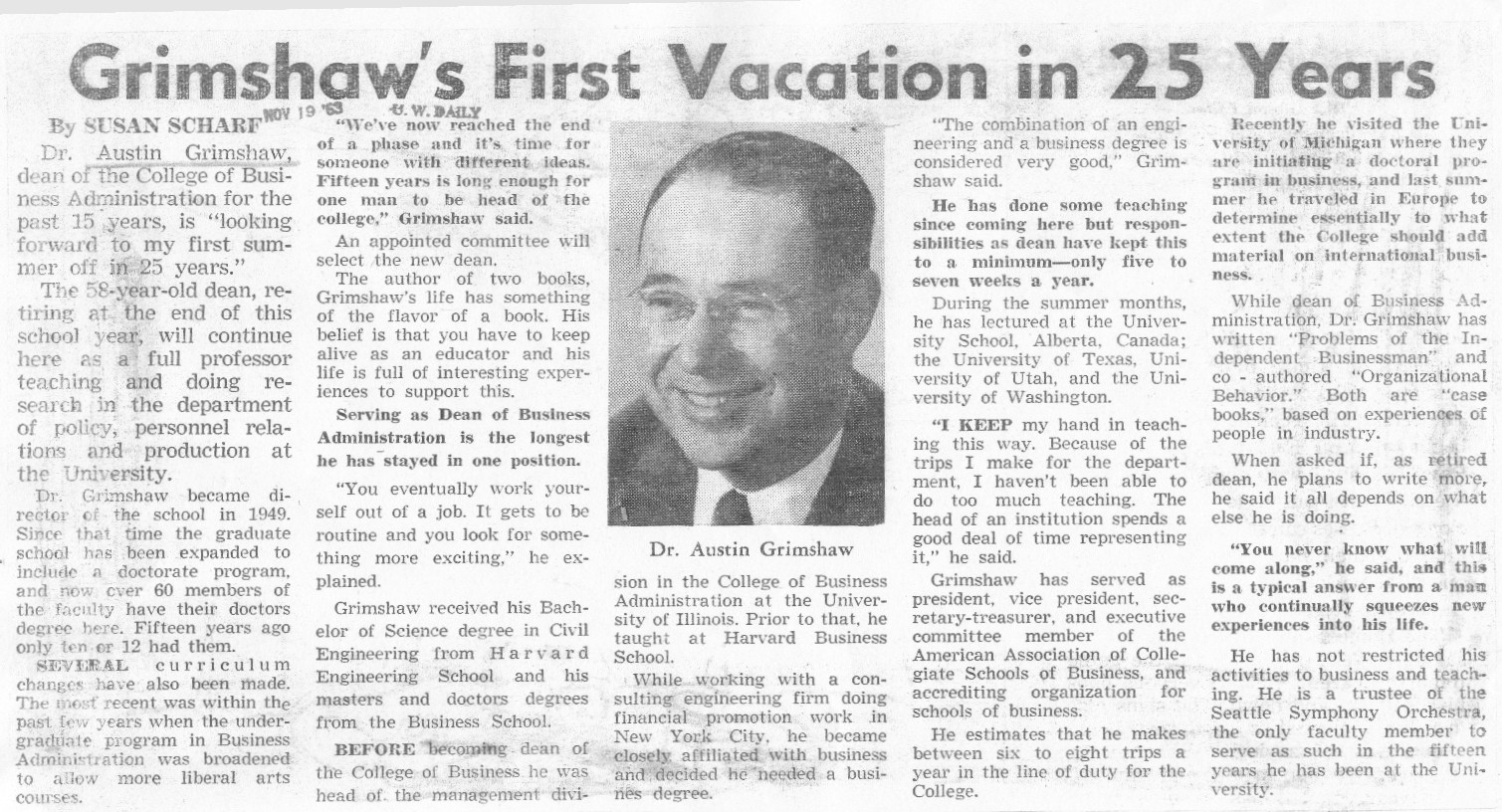

Austin Grimshaw was born in Weymouth, Massachusetts and received an engineering degree from Harvard in 1927. This degree was followed by masters (1934) and doctorate (1938) degrees, also from Harvard, in Business Administration. His doctoral thesis1,2 was entitled “Some Problems of Line Expansion and Contraction in Selected Consumer Industry Companies Manufacturing Items Retailing at Under $10.00 Per Unit”.

Dr. Grimshaw was employed at the War Production Board in Washington, D.C. during World War II and subsequently taught at the University of Illinois. In 1949 moved to the University of Washington, where he was appointed Dean of the Business School. He held that position until 1963, when he gave up the deanship and returned to teaching. He left the University in 1964, and passed away in January 1965 after becoming ill while on vacation in California.

Austin was the son of Albert Grimshaw and the grandson of Amos James Grimshaw, who are described on a companion webpage. Austin was the the great-grandson of Riley Grimshaw, who is also described on a companion webpage. Austin and Elizabeth (Day?) Grimshaw had at least two children, Allen Day Grimshaw and Anna Grimshaw Kemper, who are described on this webpage.

Contents

Photographs of Austin Grimshaw

War Production Board Assignment during World War II

Seattle Times Articles on Austin Grimshaw

Yearbook Description of University of Washington College of Business Administration

Books Authored by Austin Grimshaw

Austin Grimshaw’s Role in Building Up the College of Business Administration

Allen Day Grimshaw, Son of Austin and Elizabeth Grimshaw and Prolific Sociologist

Anne Grimshaw Kempers, Daughter and Peace Corps Volunteer

English Papers on the History of the University of Washington School of Business Administration

Webpage Credits

Thanks go to the Special Collections staff at the library of the University of Washington for assistance with obtaining photos and information on Austin Grimshaw.

Photographs of Austin Grimshaw

Photographs of Austin Grimshaw are available in the Portraits Collection of the Special Collections (negatives 2952 and 2930) of the University of Washington Library and are shown below.

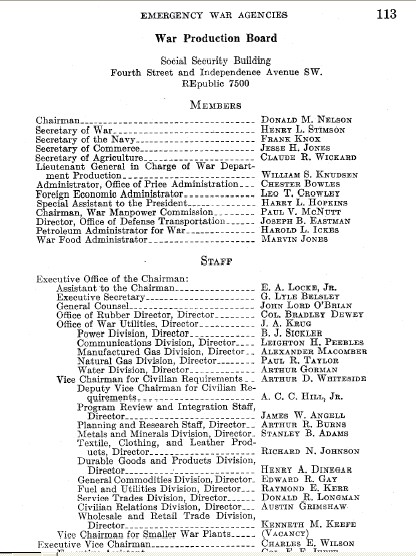

War Production Board Assignment during World War II

It appears that after graduating with his Ph.D. in Business Administration in 1938, Austin worked for a time at the War Production Board in Washington, D.C. He held the position of Director of the Civilian Relations Division under the Vice Chairman for Civilian Relations, as shown in the following page from the 1943-44 Government Manual.

http://digital.lib.umn.edu/TEXTS/014/0000FRON.PDF

United States Government Manual, Winter 1943-1944, p. 113

Office of War Information, Division of Public Inquiries, Washington 25, DC

http://digital.lib.umn.edu/TEXTS/014/0002BODY.PDF

An article from the New York Times in January 1944 covered an announcement from the War Production Board by Austin Grimshaw, as shown below (see also companion webpage):

94. WPB TO ANALYZE GOODS SHORTAGES; New Survey of Items in Civilian Use, Set for March, Will Aim at Equ… [PDF]

WASHINGTON, Jan. 19 — A second and more specific nation-wide survey on civilian consumer goods items which are in short supply will be made in March, Dr. Austin Grimshaw, who conducted the first civilian shortage census for the War Production Board’s Off…

January 20, 1944 – – Article

The complete article is shown below. A PDF of the original article can be seen by clicking here.

WPB TO ANALYZE GOODS SHORTAGES

New Survey of Items in Civilian Use, Set for March, Will Aim at Equalizing Field

Special to THE NEW YORK TIMES.

WASHINGTON, Jan 19 – A second and more specific nation-wide survey on civilian consumer goods items which are in short supply will be made in March, Dr. Austin Grimshaw, who conducted the first civilian shortage census for the War Production Boards Office of Civilian Requirements, told the Fashion Group today.

He outlined an early spring check-up which will show, for each household visited, an inventory of the textile items on hand, an estimate (sic) how long it will be before the household runs out of each item, and a statement of intended purchases of necessary articles of clothing in various sizes and at various economic levels.

As a result of the first survey of fields in which civilians reported hardships as a result of wartime restrictions, Dr. Grimshaw said, some entirely new production programs have been set up, others have been expanded, a few that might have failed for lack of sufficient information have been buttressed and some which had been keyed too high have been reduced. As an instance, he mentioned items involving rubber, which have represented a serious war shortage, but vari0us such wares will begin to reappear on the market as synthetic rubber becomes available.

Dr. Grimshaw expressed some surprise that his figures showed only 50 per cent of the women questioned as dissatisfied with the quality of wartime hosiery. On the whole, he commented, the WPB census of shortages tallied with the reports to date on a questionnaire survey conducted by the American Home Economics Association.

He stoutly defended as a time, energy and materials saver the WPB policy of not surveying shortages until they actually began to appear. Only through a three-way check, with manufacturers, retailers and consumers, can the true story of the scope of any shortage be ascertained, he said. The WPB is in such close touch with manufacturers that regular correspondence channels furnish a fairly complete check in any given field. The larger retail outlets, the mail-order houses, the big chains and department stores in general cooperate by reporting to OCR their inventories and comparisons of orders this year and last year on 300 items in civilian use.

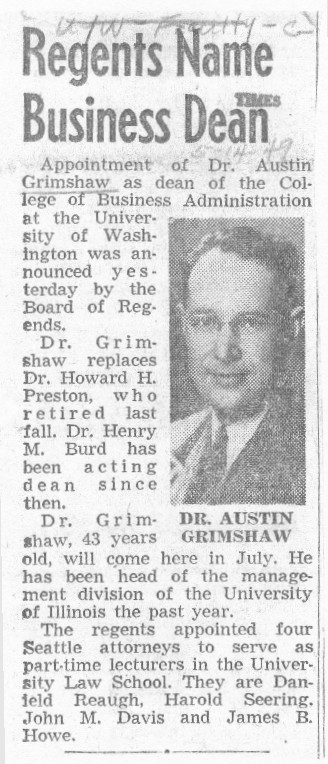

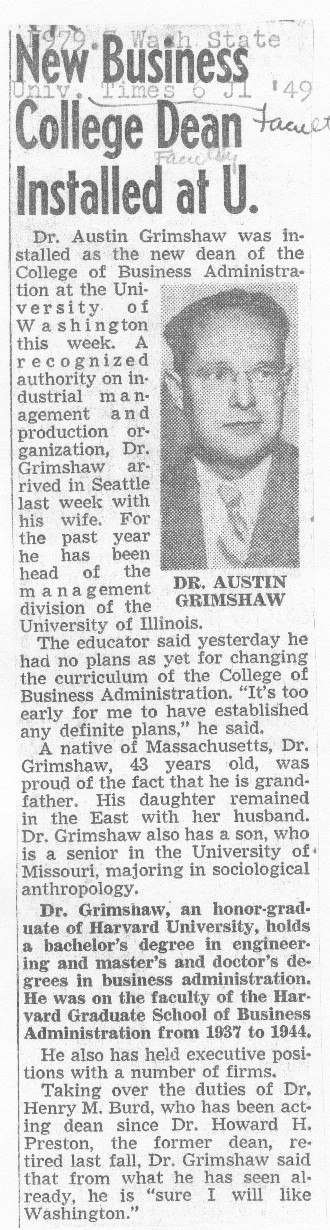

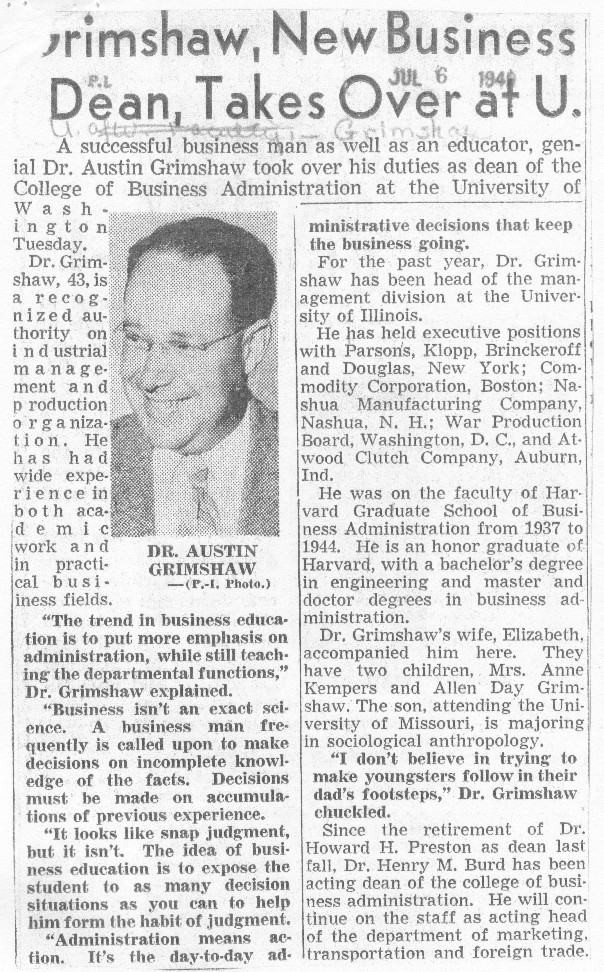

Seattle Times Articles on Austin Grimshaw

During his tenure as dean, several articles were published on Austin Grimshaw. They are shown below, from the Special Collections of the University of Washington Library.

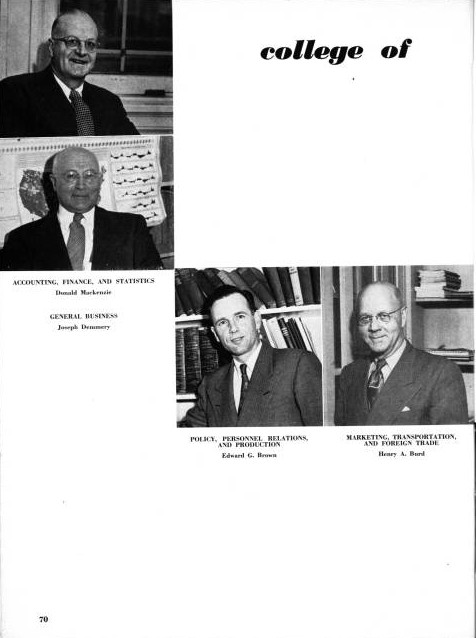

Yearbook Description of University of Washington College of Business Administration

The 1953 issue of the UW yearbook, the Tyee, contains the following information on the College of Business Administration (p. 71-72):

Books Authored by Austin Grimshaw

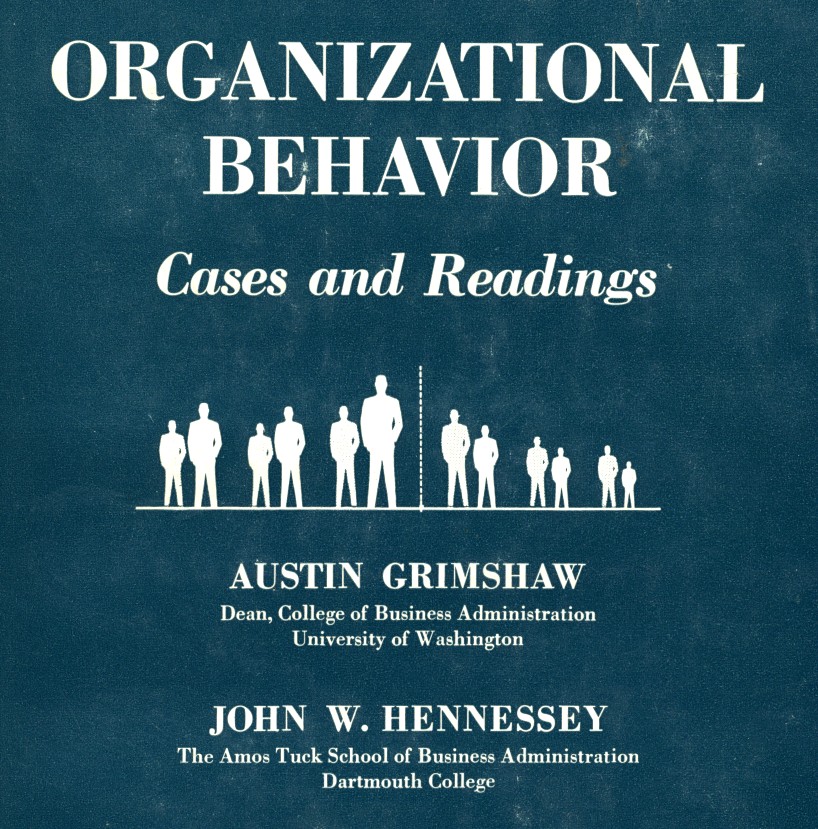

Dr. Grimshaw wrote at least two books, one on organization behavior4, published in 1955, and the other on problems of the independent businessman5, published in 1960. Images of the title pages from the two books are shown below.

Images of a review6 of the second book are provided below. Austin also became President of the Western Academy of Management in 1961; see the following webpage:

1961 Book Review of Book by Austin Grimshaw and John Hennessey:

Austin Grimshaw’s Role in Building Up the College of Business Administration

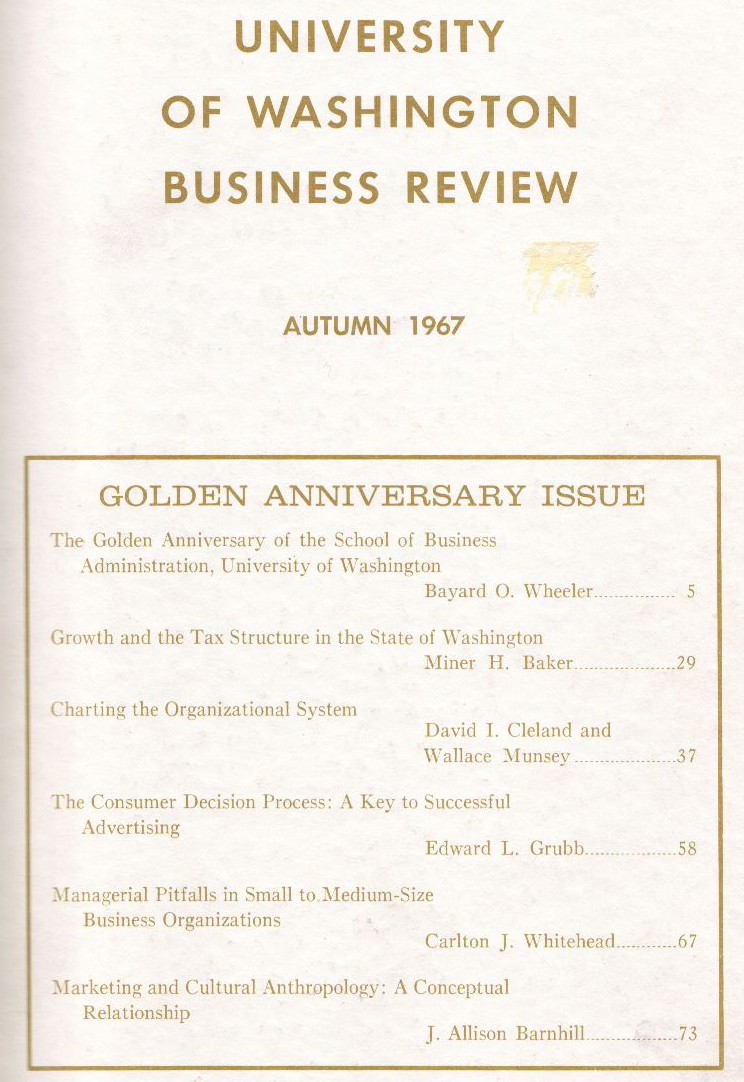

An excellent article7 on the history and development of the Business Administration College was published in the University of Washington Business Review in 1967. Images and the first part of the text of the article are provided below. An English paper on the history of the college was also prepared – by Anna Velasquez – and is provided at the bottom of this webpage.

The Golden Anniversary of the School of Business Administration, University of Washington

BAYARD O. WHEELER

The author …

Bayard O. Wheeler is Professor of Business and Its Environment, Graduate School of Business Administration, University of Washington.

In 1914 a professional curriculum in commerce was established within the Department of Political and Social Science, on an appeal from business organizations. In 1917 the School of Business Administration was created. The following article traces the development of the small school in 1917 into one of the nation’s largest Graduate Schools of Business Administration.

The School of Business Administration at the University of Washington was established in 1917 upon the recommendation of President Henry Suzallo and approval by the Board of Regents. The inception of the School, however, was not an outgrowth of pressures primarily from within the university, a situation common to the establishment of most schools of business. Rather, the stimulus came from the business community of the state even before the School was established. As stated in the 15th and 16th Biennial Reports of the Board of Regents of the University of Washington:

In 1914 a professional curriculum in commerce was established within the Department of Political and Social Science, on an appeal from business organizations. . . . In 1917 the School of Business Administration was created under the direction of Dean Carleton Parker . . . which was given the standing of an independent college.

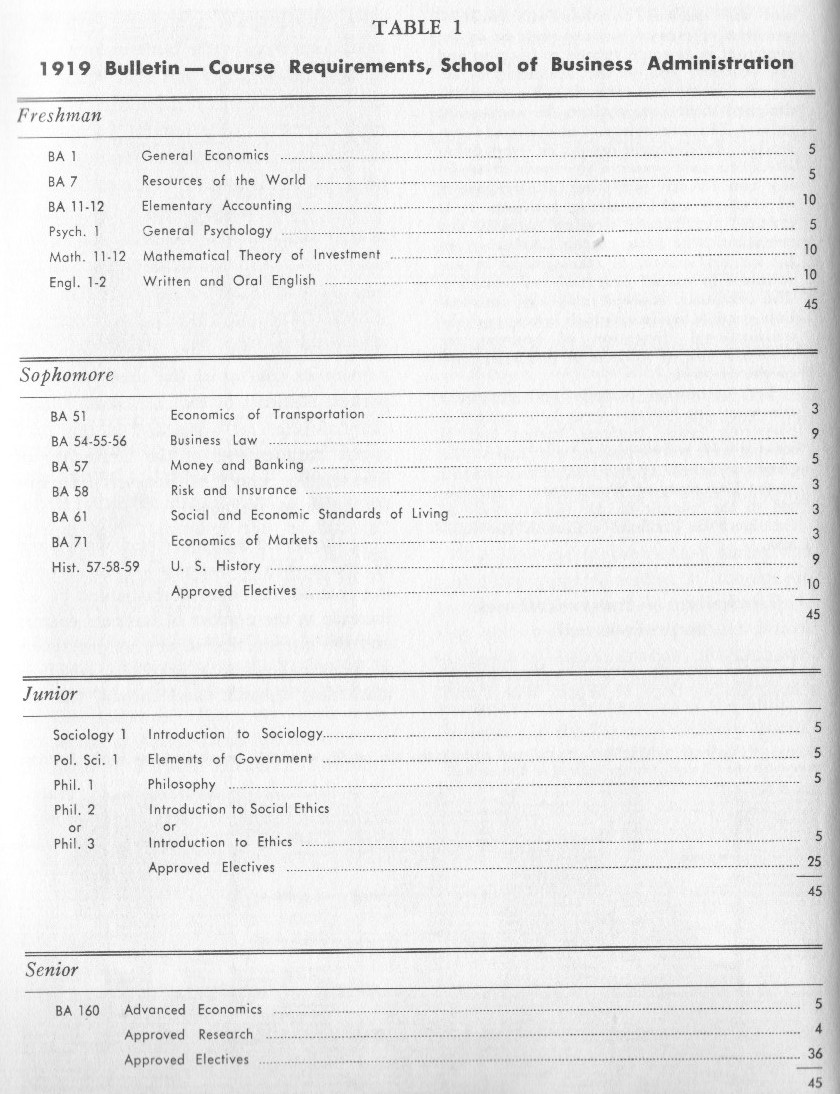

In terms of student enrollment the first year was not auspicious, with only 12 students registered in the new School under the instruction of 7 faculty members. Today’s faculty in the School of Business Administration would find this student-faculty ratio most inviting, although the earlier faculty, even as today, undoubtedly served students from other divisions of the University. o less intriguing were the required courses for Business Administration majors at this early date. In addition to accounting, statistics. insurance, and business law, there were course titles covering a broad range of liberal arts and humanities subjects. These courses illustrate the dependence at an early date of business education upon other disciplines. Faculty and textbooks in the business field were scarce Full-scale development of a professionally oriented curriculum in business came later, as more scholars entered this new and vital field of learning.

Rapid growth in early years

If the infancy of the new School was less than sensational, its rapid growth to adulthood is worth noting. In the spring of 1918, enrollment had risen to 1,350 majors, and in the autumn of 1919 the College of Business Administration (the name was changed to College from School) registered 33 percent of the University’s incoming 2.700 freshmen. As stated in the 16th Biennial Report of the Board of Regents, –The College of Business Administration thus had the heaviest enrollment of all the colleges in the University of Washington, and ranked among the four leading Schools of Commerce in the United States.”

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that in 1921 the College was invited to join the select membership of the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). Started in 1916 by some 17 schools of business including those at Harvard, Chicago, Dartmouth, and Columbia Universities, the admittance of the University of Washington business school marked the 21st school to qualify for membership. Thus, the quality of business training at the University of Washington was recognized almost from its beginning by accreditation of its curriculum and faculty to the standards of excellence established by the AACSB-now encompassing some 120 schools of business.

One cannot help but wonder why a nationally recognized school of business took root in 1917 in the relatively remote state of Washington. still in the infancy of its industrial development. It would be interesting to pursue the

thought that business and university leadership, then as today, recognized the need and importance of professionally trained personnel for the business enterprise of the state. It is more than conjecture to recognize the contribution of graduates of the University’s School of Business Administration to the rapid business and industrial growth of the state’s economy, especially following World War II.Dean William E. Cox

Such benefits cannot be measured directly from existing records, but some clues are available from the history of the School, from its response to the needs of business and from evidence of innovation and leadership in the education of business technicians and managers. Let us turn, therefore, to an account of the significant developments in the School, including its administration and leadership, its curriculum, faculty development, research, and external relations, in the order named. With this background, some insights into future opportunities and problems are suggested.

Administration and leadership

The growth, success. or failure of organizations is largely a reflection of the abilities, hopes, and aspirations of their administrators and supporting personnel. Schools of business are no exception. This is evident in the attitudes and policies of the eight deans who have served the School from Dean Parker in 1917 to Dean Hanson in 1967. Of the first four deans, the following editorial comment in the University of Washington Daily in June 1928 is revealing:

A builder, a promoter, an educator, and an able administrator-these have been the outstanding characteristics of the four deans who have served at the head of the College of Business Administration.

The builder, Carleton H. Parker, was brought to the University in 1917 to form the college and give it a firm foundation. He did this in the one short year that he served the University.

Stephen I. Miller, the promoter, came next, and under his able guidance the college grew rapidly. He stayed on the campus until 1923, when he was appointed educational director of the American Institute of Banking.

The essence of efficiency, Howard T. Lewis, the educator, was third in line. Aside from his University tasks, he made numerous journeys to the Orient to promote trade and good feeling between the Orient and the Occident. Dean Lewis left the University in 1926 to accept a position in the Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration

The present dean, William E. Cox, has made no drastic changes in the policy of the college, but has succeeded in liberalizing the curriculum and has personalized the friendship between faculty members and students. f)ean Cox came to the University in 1919 with primary interest in accounting, and an educational background at the Universities of Texas, Stanford, California, Chicago, and Harvard.

Dean Howard H. Preston

Dean Cox came to the University in 1919 with primary interest in accounting, and an educational background at the Universities of Texas, Stanford, California, Chicago, and Harvard.

Upon Dean Cox’s appointment as Comptroller of the University in 1931, Professor Shirley J. Coon became the fifth dean. With a strong background of graduate training in economic theory, Dean Coon epitomized the “scholar” in his teaching. publications, and faculty leadership. He joined the faculty of the College in 1927 following the receipt of his doctorate at the University of Chicago in 1926. Ill health forced his resignation from the deanship in 1938.

Dean Coon’s successor, Professor Howard Preston, had served on the faculty of the College as an authority in money and banking since the early 1920’s, following the completion of his doctorate at the University of Iowa in 1920. During this time, as under prior deans, the College combined the curriculum and faculties of business and economics, but in 1948, at the time of Dean Preston’s resignation to resume his teaching career, the economics segment was transferred to the College of Arts and Sciences. The reconstituted College of Business Administration retained college status. A change in title to the School of Business administration, a return to the name at the founding date of 1917, was made in 1967, following the change a year earlier to the name Graduate School of Business Administration for graduate programs.

Dean Austin Grimshaw

Dean Preston’s tenure marked a period of turbulence on the national and state levels, during the Great Depression and the following World War lI years. Moreover. the field of business administration was emerging as a distinct discipline, in which scholars were anxious to assert independence from economics. Washington’s School of Business was the last major school on the Pacific Coast to make the change. If former deans of the School can be characterized as builder, promoter, educator, administrator, and scholar, Dean Preston filled the role of educator and “good father” to students and faculty. He immersed himself deeply in the problems and aspirations of those he served.

The succession of Austin Grimshaw to the deanship in 1949, following Professor Henry Burd’s acting deanship, marked a distinct change in the educational orientation and objectives of the College. With a background of training and teaching at Harvard, fortified by managerial experience in business enterprise, he brought the experience and attitudes of the “professional” business executive, concerned with management and the art of decision making. As a dynamic “innovator,” he moved the College into the mainstream of business training and structured the educational framework within which Dean Kermit Hanson has moved the School ahead to its present level of excellence.

Dean Kermit O. Hanson

Among the many outstanding professors who contributed significantly to the early development of the College, alumni will recall the names of Henry A. Burd – who also served as Acting Dean in 1938-1939-Raymond F, Farwell, Homer E. Gregory, Donald H. Mackenzie Carl S. Dakan. James A1. Mcconahey, and Macy M. Skinner. Perhaps most vividly remembered is Professor Cox. Although his service in the deanship was brief, no one contributed more to the growth and development of the College. His membership on the faculty dated from 1919 until his retirement in 1957, and his devotion to the cause of higher education for business continued until his death in 1966. Professors S. Darden Brown, Joseph Demmery, Nathanael H. Engle and Frank H. Hamack retired in recent years after long and meritorious service. A listing of current faculty members appears following this article, but it would be remiss not to mention at this point three who have served faithfully and well for more than half of the lifetime of the College-Arthur N. Lorig, Charles J. Miller, and Julius Roller.

Dean Kermit Hanson came to the University of Washington in 1948 with an educational background of teaching and training for the doctorate at Iowa State University. In addition to teaching and research in the fields of accounting, statistics, and finance, he served the College in various administrative roles, including department chairman, director of graduate studies, and associate dean. As teacher, author, consultant, and administrator, he accepted the deanship of the College in 1964 following the retirement of Dean Grimshaw.

The progress of the School during the past three years is evident in subsequent portions of this report-in curriculum revision, the creation of the Graduate School of Business Administration, marked success in faculty recruitment and acquiring research funds, the founding of the Affiliate Program and the Business Advisory Board, the strengthening of tics with the business community, the development of a computer center, and enlightened concern for high level professional training at both the graduate and undergraduate levels. Dean Hanson’s concern for excellence is evident in the future plans and aspirations for the School, discussed later, and in his following report to the business faculty:

Looking to the future in this age of increasingly rapid change, American industry, if it is to maintain its position of world leadership, should devote more attention to research and innovation, sophisticated techniques of management, and economic growth and the external environment. Similarly, graduate schools of business must be in the forefront in research related to business and the economy and to the utilization of research in a constant renewal of a curriculum designed to prepare students for managerial careers. The importance of teaching and curriculum development cannot be overemphasized; we must preserve the status of teaching concurrently with our encouragement of research and consulting activities. It is essential that faculty develop curricula for executives who seek greater proficiency in the art and science of management by enrollment in special programs and seminars. The computer, strategic planning, information systems, environmental forces, and the multinational dimension of business are among a host of subjects of immediate and specific concern.

Both American business and American education for business have large stakes in preparing future business leaders and in seeking new knowledge and techniques. The Graduate School of Business Administration at the University of Washington is committed to the pursuit of the highest level of excellence in graduate education for business.

Curriculum – from vocational to professional

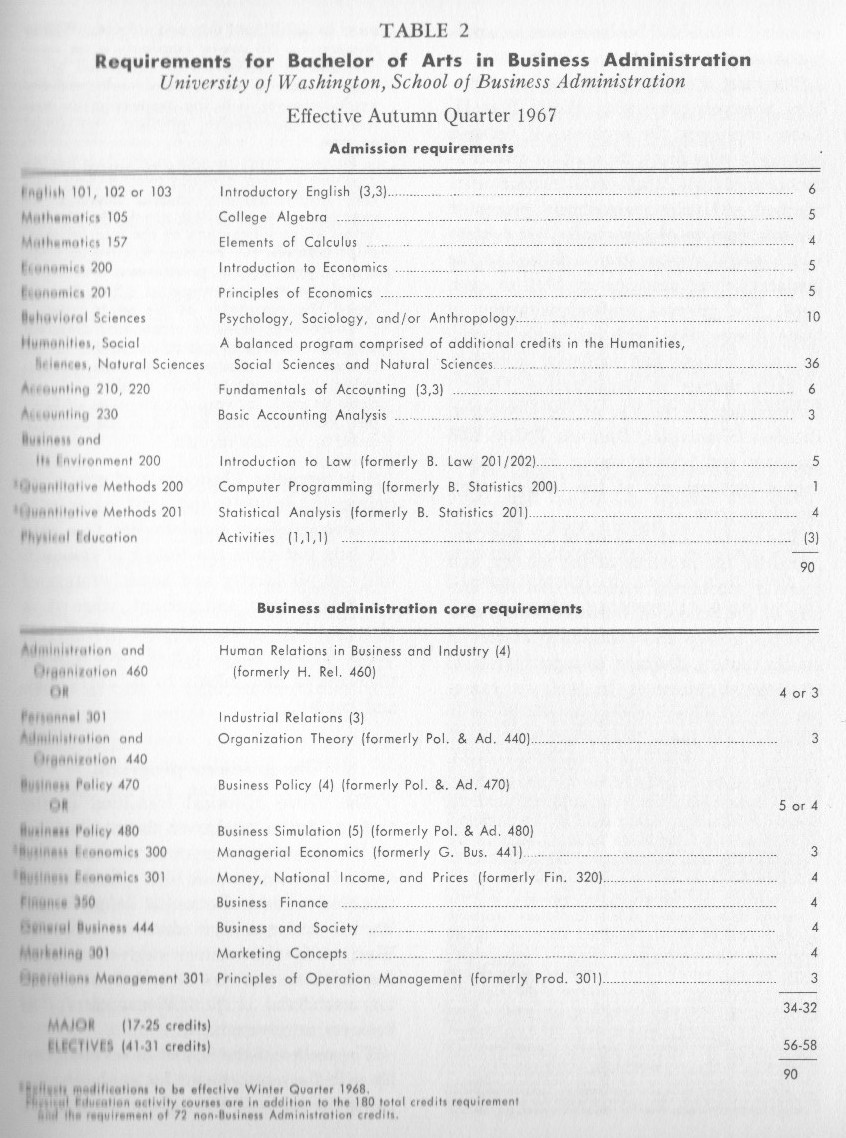

Changes in the curricula of business schools dating back to World War I and earlier came largely in response to developments occurring in the business system. In the period just before and after World War I, courses in collegiate schools of business reflected the growing interest in the identification and description of business enterprise as an emergent institution in an economy previously largely agricultural and rural. Curriculum content was largely descriptive as business scholars probed into the nature of business activities and studied the business firm and its functions. But. then as now, the liberal arts and humanities courses of the times were important elements in the curriculum. These characteristics are suggested in the 1919 course requirements of the University of Washington School of Business Administration shown on page 12 (Table 1).

In the period between World Wars I and II. the growth of business and its increasing complexities were accompanied by an increase in the number of business courses and the introduction of new subjects such as industrial relations. statistics, retailing, marketing research, and income tax accounting. Schools of business were attempt-ing to adapt to the needs of business.

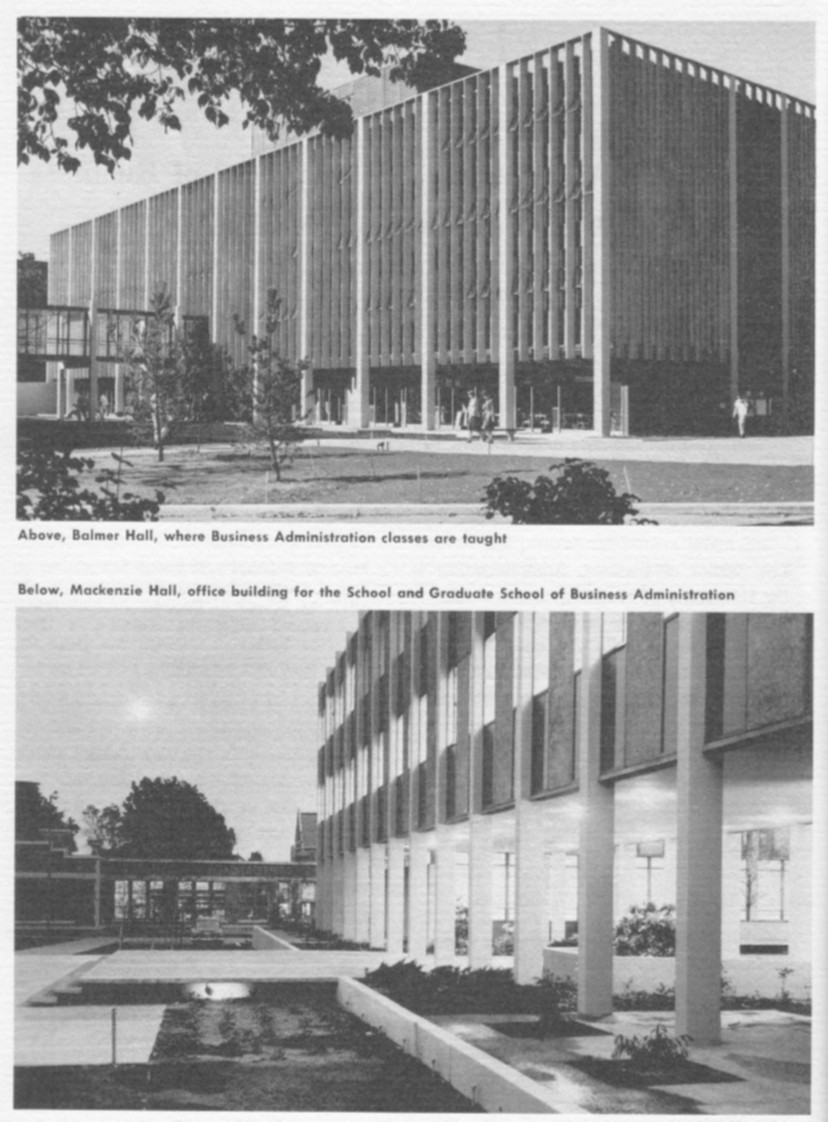

Copies of business publications, books and periodicals, are readily available for student use in the Business Administration Branch library located in Balmer Hall

The most drastic innovations in curriculum, however, came after World War II. Labor shortages, the problems of decision making in large firms, the need for quantitative controls, and the overall requirements of good enterprise management prompted the introduction of new curriculum content which would appear strange indeed to the business school graduate of 1919 or even 1939. The growing professionalization of business education, with increasing emphasis upon analysis and methods, is evident in such courses as Organization Theory, Introduction to the Use of the Computer, Business Simulation, Business Policy. and Business and Society shown in the latest course requirements of the School reproduced on page 13 Table 2).

The content and revision of curricula are primarily the province of the faculty, and there is substantial evidence that the faculty of the School of Business Administration has a deep and continuing interest in course content designed to meet high-level educational objectives. In 1960. for example, the College faculty stated its basic philosophy in the following terms:

The major mission of the College of Business Administration is to graduate students with substantial background in the underlying fields of knowledge basic to responsible citizenship and essential to an understand_ ing of business as a leading social institution of our time. Education for business is perceived as a lifelong, not a four-year, process. The curriculum is designed to provide the student with a sound foundation upon which he may continue his learning experience after graduation. The college thus becomes a catalyst for the instilling of values and ways of thought about one of man’s most important activities business-and the society in which it operates.

The student learns to view business as a segment of the whole of knowledge, with roots in the liberal arts and sciences. Within this setting, his major emphasis is on business and its specialized or functional areas. Approximately half of his undergraduate work, however, is in the communication arts and the quantitative, physical and social sciences.

Through exposure to a curriculum having a proper balance between business and relevant disciplines, the student develops an inquiring and analytical mind. He also acquires an understanding of the interrelationships between the business world – its institutions, philosophies, policies and procedures -and the social universe in which he will spend the remainder of his adult years.

The college seeks to create and maintain an intellectual atmosphere conducive to the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. It strives to encourage both faculty and students to push forward the frontiers of business knowledge and to lead in the development of business thought.

The preceding illustrations of course requirements in 1919 and 1967 cover only the undergraduate requirements. One cannot help but sense the feeling of responsibility of all faculty and administrators of the School, past and present, when it is observed that a total of some 80.000 students enrolled in the School have exposed their minds and talents to its curriculum and faculty.

The graduate program

The article continues…

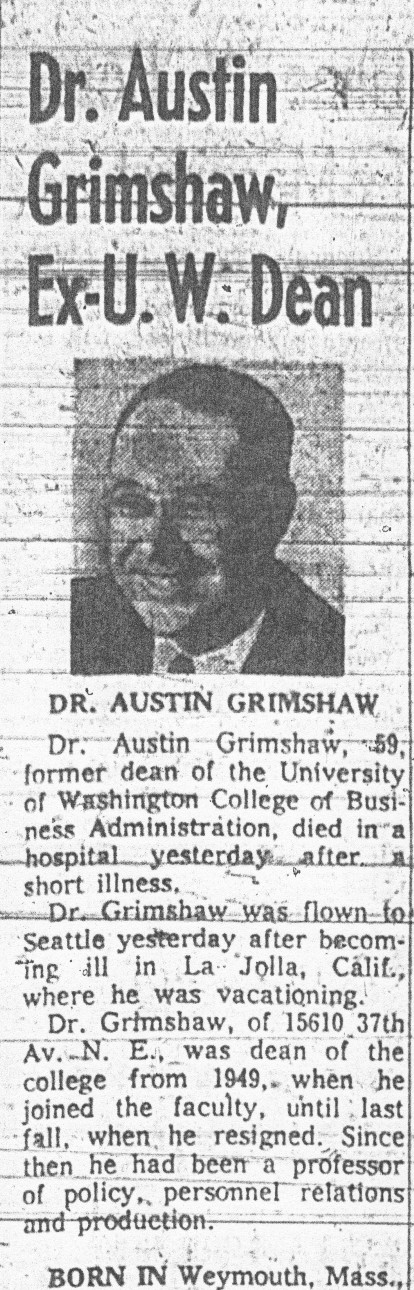

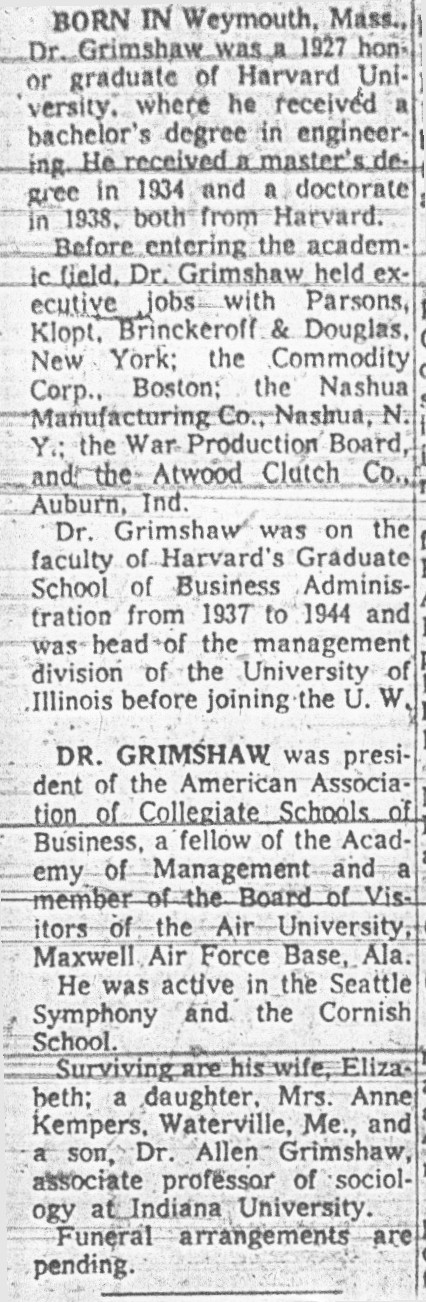

Austin Grimshaw’s Obituary

Dr. Austin Grimshaw died suddenly at the young age of 59 not long after leaving his college dean position in 1963. He became ill while on vacation in California in January 1965 and died shortly thereafter. His obituary is shown below.

The Seattle Times, Thursday, January 14, 1965, p. 17:

Allen Day Grimshaw, Son of Austin and Elizabeth Grimshaw and Prolific Sociologist

Austin and Elizabeth Grimshaw’s son is an emeritus professor of sociology at Indiana University and author of many books and academic papers.

Allen D. Grimshaw

Emeritus Professor Allen D. Grimshaw joined the Department in 1959 as an Instructor; he retired in 1994 after teaching from 1951 onwards (with brief interruptions for military service and for research leaves and sabbaticals).

He began his undergraduate work at Purdue (!), holds B.A. and M.A. degrees from the University of Missouri and a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania. During his nearly fifty years of teaching and research he has focused primarily on social conflict and on language in use in social contexts and on interaction of the two phenomena; he has published a number of books and many articles on these and related topics.. Since retirement he has published encyclopedia and handbook articles on riots in the United States, on genocide, and on a variety of topics in sociolinguistics; he is currently engaged in several research and writing projects. He continues to lecture both in the United States and abroad; much of his and his wife Polly’s travel involves final destinations where one or more of their grandchildren can be found. He is particularly proud of his past undergraduate and graduate students, of successful fund-raising for the department, and of continuing to walk fifteen to twenty miles each week. He wishes he could be equally successful with new electronic wizardry from VCRs, to scanners, to power point technologies. He will not be able to help you with problems in “eighty-seven and a half way analysis of variance.”Allen and his wife, Polly (Swift) Grimshaw, established a lectureship and professorship at Indiana University in 2001, as described below.

ALLEN D. AND POLLY S. GRIMSHAW LECTURESHIP AND PROFESSORSHIP

Emeritus Professor of Sociology Allen Grimshaw and Emeritus Librarian Polly Grimshaw donated funds in 2001 to create the first endowed professorship in Sociology at IU, the Allen D. and Polly S. Grimshaw Professorship, and a similarly named endowed lecture series. The Grimshaw Professor serves for five years; the first Grimshaw Professor, named in 2001, is Brian Powell.

Polly Grimshaw, Brian Powell, and Allen Grimshaw

In donating funds for the Grimshaw Lecture Series, Allen and Polly wanted the Lecturers to reflect the range of methodological and theoretical orientations and interests of sociologists and sought to nourish catholic and cosmopolitan views, by sociologists and non-sociologists alike, of what constitutes the sociological enterprise. They established the Grimshaw Lecture Series as a showcase of sociological innovation as well as imagination. The visiting Lecturer delivers a lecture to the university, visits with a sociology class as a guest lecturer, and meets informally with sociology faculty and graduate students.

Past Allen D. and Polly S. Grimshaw Lecturers include:

2001 Donald Black “Adventures in Pure Sociology”

2002 Michael Burawoy “Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: Bringing Theory and History to Ethnography”

2004 Paul DiMaggio “Digital Inequality: How is the Internet Influencing Social Stratification in the U.S.?”

2005 Paula England “Hook Ups, Dates and Relationships on Todays College Scene”

2006 Lawrence D. Bobo “Unfair by Design?: Race, Public Opinion, and the New Law & Order Regime”

Donald Black delivers Inaugural Grimshaw Lecture

Allen D. Grimshaw (b.1929; IU Sociology 1959-1994) and Polly S. Grimshaw (b. 1931, IU Library 1965-1996) have been members of the Indiana University and Bloomington communities for forty-five years. Allen took a B.A. in Anthropology and an M.A degree in Sociology from the University of Missouri in 1950 and 1952. Following two years in the US Air Force, he returned to school and earned his doctorate in Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania in 1959. Polly, after beginning her studies at Monmouth College in Illinois, earned her B.A. at Missouri in 1953. Some years later she returned to school and earned an MLS at Drexel University in 1957.

Allen and Polly are highly regarded both professionally and as citizens of IUB. Allen has been a much-loved colleague, teacher, mentor, and friend since he came to Bloomington as an instructor in sociology in 1959. Allen wrote some 200 publications (books, edited volumes, special issues, chapters, refereed articles, and reviews and review articles in major journals in anthropology, linguistics, sociology and specialty areas) on a wide range of topics. His primary interests included social conflict and social violence and the use of language in social contexts (sometimes called sociolinguistics), an area for which he has been a strong proponent in faculty meetings over the years. One of his students, Curt Simic, now President of the IU Foundation, wrote about Allens life work, He brings to issues a balanced understanding and a broad, humane, and caring vision.” Allen held several dozen appointive and elected offices, editorships, and panel memberships in a wide range of scholarly associations and institutions. He was recognized by the Peace and War Section of the ASA for Distinguished Contributions to Scholarship, Teaching, and Service and by the Directors of the Indiana University Foundation with a Resolution of Appreciation for his many services to the Foundation. Since his retirement in 1994, Allen has continued to be active in publishing and promoting teaching about the horrors of genocide.

Photo by Paul Martens

Polly was the Liaison Librarian for Anthropology, Folklore, Gender Studies, and Sociology, and Director of the Human Relations Area File. Polly s extensive knowledge of the literatures of all these fields and her exceptional skills as a reference librarian attracted a steady stream of students and faculty to her office over the years. Polly served on elected committees of the American Library Association and elected and appointed positions on a number of IU committees and governing bodies, including the all-campus IU Library Council. At one time Polly and Allen served together as elected members of the IU University Faculty Council. In addition to her regular faculty responsibilities as liaison librarian, she helped initiate and then supervised the MLA Folklore Bibliography Project. While most of her writing was related to professional responsibilities, she found time to write Images of the Other (1991), a major book evaluating microfilm collections on American Indian/white relations. Generations of graduate students in the fields for which she was responsible acknowledged her freely-given bibliographic assistance and counsel and encouragement. Perhaps the best testament to Polly s years of service at the library is the strength of the collections that she built up; in that sense, she continues to serve the social sciences community at IU. In 1988 she was selected by her peers to receive the William Evan Jenkins Librarians Award for her outstanding contributions to the Indiana University Libraries.

Beyond their many professional accomplishments, Allen and Polly are warm, caring and generous people-and by many accounts the best story-tellers in the department. Their gift of the Grimshaw Lecture Series and Professorship will benefit the Sociology department and the broader university community for generations to come. A news story about the Grimshaws donation is available at: http://www.homepages.indiana.edu/101201/text/legacy.html.

Information on Polly (Swift) Grimshaw

http://www.indiana.edu/~libadmin/iuln/6iuln21.html

IUL News for May 28, 1996 Volume 23, Number 21

1. IN HONOR OF THE IUB LIBRARIES 1996 RETIREES

Polly Grimshaw

Polly Swift Grimshaw was born in Baltimore, but since her mother later entered the diplomatic service, she attended 23 schools in this country and abroad in the course of her education. She received her A.B. degree from the University of Missouri, where s he met her husband Allen. After completing her MLS at Drexel, she began her library career in the Social Science and History Division of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

The Grimshaws moved to Bloomington when Allen joined the Sociology Department here, and on January 4, 1965, Polly assumed her position as Bibliographer for Sociology, Anthropology and Folklore for the Indiana University Libraries. The first incumbent in t hat position, she held it (with various title changes and added responsibilities) for thirty-one years, until her retirement at the end of 1995. When the Women’s Studies program began, she began covering that area, and in 1993 she added Psychology as well . She also supervised the Human Relations Area Files. In 1978 she was promoted to the rank of Librarian.

Polly was closely involved with each of the departments she served, aware of research needs, offering instruction to classes and participating in team teaching. Her special contributions were recognized with two additional titles, Adjunct Professor of Wom en’s Studies, in 1986, and Adjunct Professor of Folklore, in 1992.

Polly’s contributions as a Subject Librarian were marked by two outstanding attributes. First, she mastered the literature of her fields, read widely in each, and participated actively in the professional organizations of each. Second, she had a special g ift for sharing her knowledge, assisting a steady stream of faculty and students who came to her office for help and guiding generations of students in a wide variety of academic programs.

The outstanding reputation of the Folklore Collection, and Polly’s internationally recognized expertise in that field, led to a heavy volume of questions from around the world, arriving by mail, telephone and electronically. In 1989 the Folklore Volume of the MLA Bibliography moved to Bloomington, where it has been compiled under Polly’s supervision. A vastly improved publication has resulted.

Polly’s special interest in Native Americans led to the publication of her book, “Images of the Other: a Guide to Microfilm Manuscripts on Indian-White Relations, in 1991.”

Polly has participated in a wide variety of library and campus committees. She chaired the committee charged with establishing faculty status for librarians, and served on the committee that drew up the Bloomington campus

Affirmative Action guidelines. Those of us who worked closely with her learned much from her steady vision of the Libraries in general, and the Main Library Research Collections in particular, as a unified whole, serving users whose needs are not delineated by narrow subject divisions or classification schemes. She communicated that vision through her own ongoing learning, her tireless attention to detail, and her constant readiness to serve library patrons at any level who called on her for assistance. Polly’s unique contributions were recognized by her colleagues when in 1988 she was chosen for the Jenkins Award.Polly’s plans for retirement include working on her current research project a study of cultural encounters with Native Americans as reflected in letters from seventeenth century New England immigrants, and traveling with her husband Allen. Her contributions remain with us as generations to come benefit from the rich library collections she has built for us all.

Obituaries for Polly Grimshaw…

Obituaries – October 19, 2006: www.HeraldTimesOnline.com

14, 1931-AUG. 17, 2006. A memorial service in celebration of the life of Polly Swift Grimshaw will be 3 p.m. Saturday at the Indiana University Foundation. …

www.heraldtimesonline.com/stories/2006/10/19/obit.obits.sto – Similar pages Obituaries – October 15, 2006: HeraldTimesOnline.com

A memorial service in celebration of the life of Polly Swift Grimshaw, 74, of Bloomington, who died Aug. 17, 2006, will be held 3 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 21, …

www.heraldtimesonline.com/stories/2006/10/15/obit.obits.sto – Similar pages

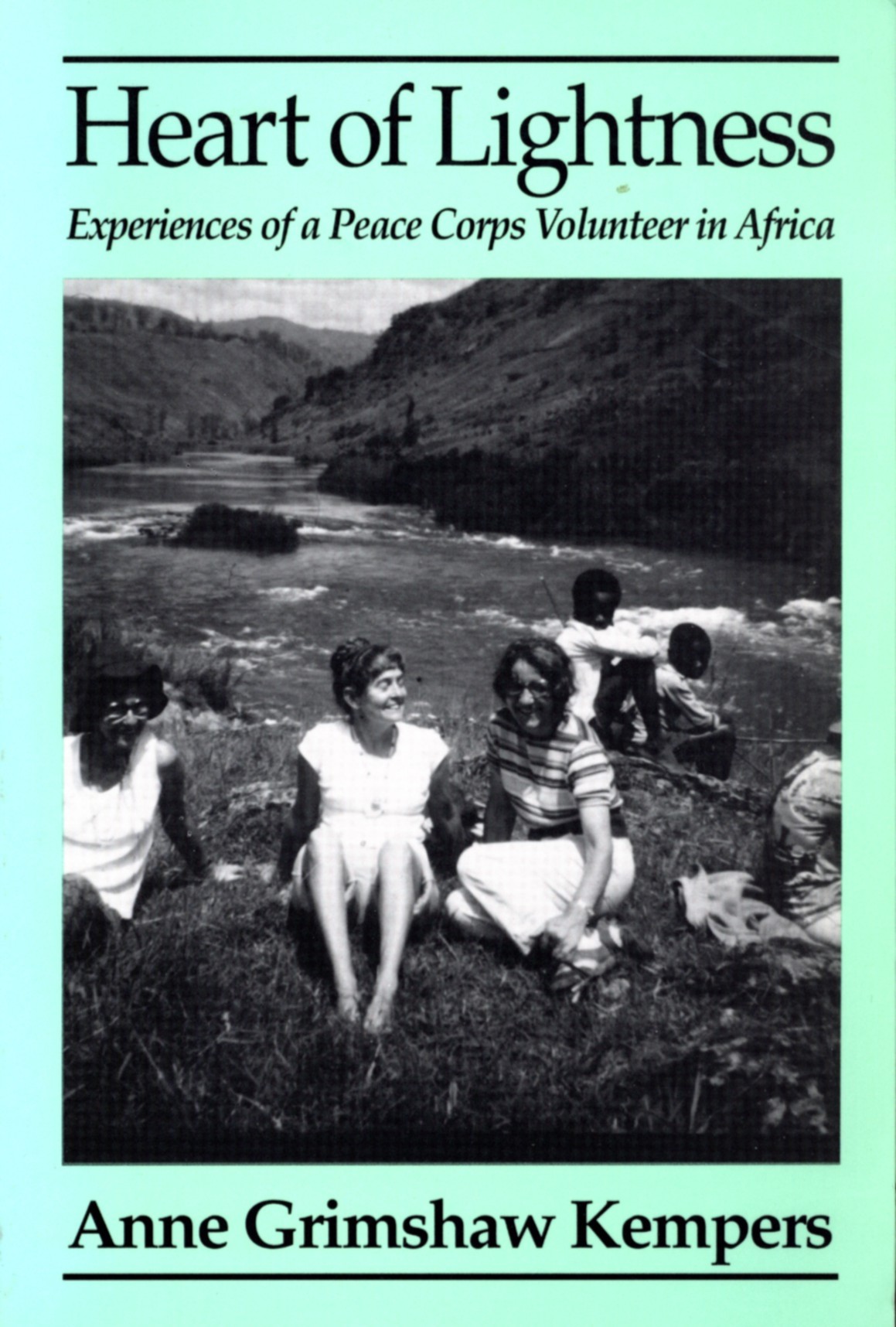

Anne Grimshaw Kempers, Austin’s Daughter and Peace Corps Volunteer

Anne Grimshaw, daughter of Austin and Elizabeth Grimshaw, joined the Peace Corps at a later than usual time in her life and spent two years in Zaire, which are described in her book, “Heart of Lightness”.

Book Cover

“Tridi, myself and Cecelia, an Italian volunteer, during our hike down the Ruzizi, spring, 1978.”

From the back cover….

Heart of Lightness

Anne Grimshaw Kempers

Not all Peace Corps Volunteers are idealistic young people, fresh from college and eager to challenge themselves and to change the world. Anne Grimshaw Kempers celebrated her fiftieth birthday while serving in the Peace Corps in Zaire, the former Belgian Congo, located in Central Africa.

Mother of four and a teacher of French for twenty years, author Kempers had an experience different from that of the majority of Volunteers. Her “totally positive” tour of duty also contrasts sharply with Joseph Conrad’s grim tale of the Congo, Heart of Darkness.

Assigned to a teachers college to teach English and language teaching methods to mature students, she lived in a large city located at a relatively high altitude with consequent temperate climate. She enjoyed good health and many modern conveniences. This was not the situation of most volunteers, who lived in rural settlements helping villagers with agricultural, sanitary or domestic projects.

Kempers writes about her two years’ service with enthusiasm and humor. A series of happy circumstances plus a liberal dose of serendipity made her experience less difficult and more rewarding than many. She had far fewer adjustments in dealing with a different culture than most volunteers. Her challenge arose when she returned to the States and found that the changes in herself presented “re-entry” stumbling blocks to settling back into her former routine. This is a common situation for most volunteers, though seldom treated in their tales of adventure on site. Kempers examines the readjustment with concern and thoughtful insight.

Peter E. Randall Publisher

Box 4726, Portsmouth, New Hampshire 03802

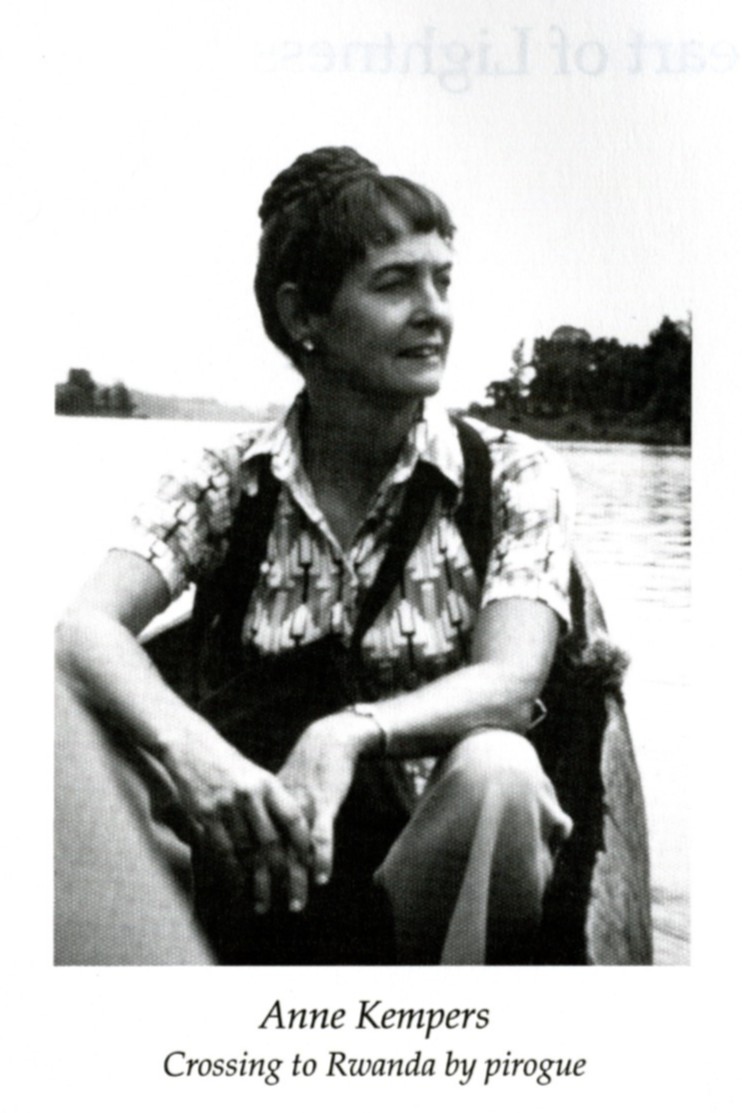

Anne Grimshaw Kempers, from “Heart of Lightness”…

Image from Anne Grimshaw Kempers’ book…

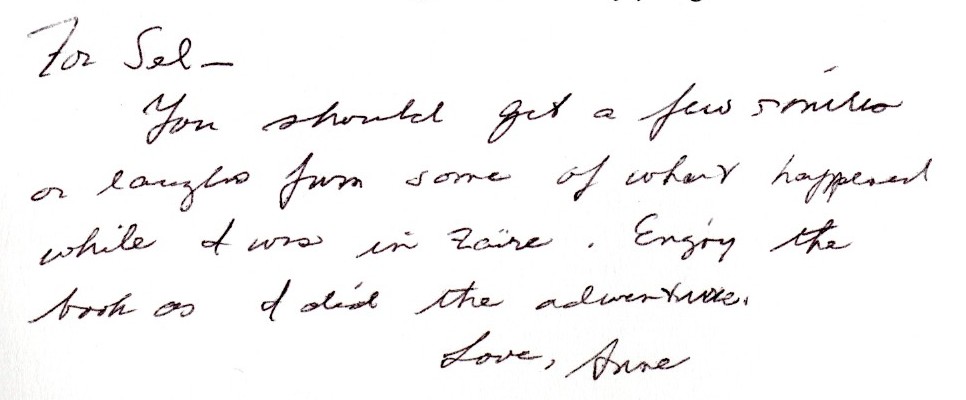

Anne’s signature from an autographed book…

Fortuitously, there was a copy of the following name tag in the book purchased for this webpage, indicating “Sel” to be Selma Weiss Coons, the apparent recipient of the book.

Wass Anne a French teacher before entering the Peace Corps?

Letter to the Editor Anne G. Kempers

The French Review, Vol. 41, No. 6 (May, 1968), p. 872Anne Grimshaw Kempers was apparently a graduate of the University of Rochester, New York. Her death was noted in the “Rochester Review” — dated Winter 1999-2000 — as occurring in January 1995.

ALUMNIAnne Grimshaw Kempers, ’57 (MS), ’57W (MS), January 1995

Source: http://www.rochester.edu/pr/Review/V62N2/cn-inmem.html

Austin Grimshaw’s Family Line

Austin Grimshaw’s ancestors and descendants are shown below as an extension of chart included on the webpage on his father, Albert Harvey Grimshaw (see http://test2.grimshaworigin.org/grimshaw-origins-history/albert-harvey-grimshaw/). Thanks to Mavis Long for providing the following descendant chart (now with Austin Grimshaw information added).

George Grimshaw (1801, Church – 7 Jan 1836) & Mary Melling

|—James Grimshaw (1825 – ?)

|—Esther Grimshaw (1827 – ?)

|—Mary J Grimshaw (1830 – ?)

|—Riley Grimshaw (2 Feb 1831 1836, Musbury, Haslingden – 1866, b Royton) & Margaret Briggs. Married 4 May 1854, St Mary’s Church (now Blackburn Cathedral), Blackburn.

|—|—Amos James Grimshaw (1854, Darwen – 29 Jun 1902, RI) & Anna Austin (1853 – 11 Jan 1889). Married 6 Jul 1881.

|—|—|—Albert Harvey Grimshaw (29 May 1883 – 20 Apr 1949, Raleigh, NC) & Bertha LeCain (1884 – 1953)

|—|—|—|—Catherine (or Katherine) Louise Grimshaw (16 Aug 1904, Keene Town, NH – 1948) & Unk Herman

|—|—|—|—Austin Grimshaw (ca 1905, Weymouth, MA – 13 Jan 1964, Seattle, WA) & Elizabeth Day?

|—|—|—|—|—Allen Day Grimshaw (1929 – ) & Polly Swift (1931 – 17 Aug 2006)

|—|—|—|—|—Anne Grimshaw (? – Jan 1995) & unknown Kempers

|—|—|—|—|—|—Tasha Kempers

|—|—|—|—|—|—Peter Kempers

|—|—|—|—|—|—Margo Kempers

|—|—|—|—|—|—David Kempers

References

1Grimshaw, Austin, 1950, Some Problems of Line Expansion and Contraction in Selected Consumer Industry Companies Manufacturing Items Retailing at Under $10.00 Per Unit: Boston, MA, Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration, Ph.D. Thesis, 416 p. (Available at Harvard University Library).

2Grimshaw, Austin, 1937, A companion case book to “Organization and management of a business enterprise: Boston, MA, Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration, Cases arranged by Austin Grimshaw. 1937. Apparently never published. (Available at Harvard University Library).

3The Tyee: University of Washington Yearbook, 1953

4Grimshaw, Austin and John W Hennessey, 1960, Organizational Behavior: Cases and Readings: New York, McGraw-Hill, 505 p.

5Grimshaw, Austin, 1955, Problems of the Independent Businessman: New York, McGraw-Hill, 403 p.

6Summer, Charles, 1961, Book Review of “Organizational Behavior: Cases and Readings”: Management Science, v. 7, issue 4, p. 451-2.

7Wheeler, Bayard O., 1967, The Golden Anniversary of the School of Business Administration, University of Washington: University of Washington Business Review, v 27, no 1 (Autumn 1967), p. 5-28.

Grimshaw, Austin, date unknown, Determination of Product Line Composition: unknown publisher, 1 vol, Section I, II and III, Appendix Cases

Webpage History

Webpage posted July 2007. Upgraded August 2007 with information on Allen Day Grimshaw and Anne Grimshaw Kempers.

English Papers on the History of the University of Washington School of Business Administration

Two papers were prepared by Azalea Vasquez in 1998 on the history of the

University of Washington School of Business Administration, which

included paragraphs on Dean Grimshaw’s tenure at the school. These papers are shown below with the paragraphs on Dean

Grimshaw shown in bold.First Paper:

English 281 C

Azalea Vasquez

Assignment 3

[3/6/98]

A Brief History of The UWs School of Business Administration

Introduction

As the title implies, this report will only cover bits and pieces of the business schools history. During weeks of continuous research in the UW archives, and meetings with the extremely helpful staff of the business school; most of the information that I discovered was unfortunately not very in-depth. There is no detailed formal history of the school that is commercially published, chronicling the people and events that have impacted it which could have filled in the blank or sketchy spots. Despite this I was able to uncover some very interesting information. This report begins with the creation of the business school in 1917, focuses on the hardships encountered during the reevaluation and upgrading of the undergraduate and graduate curriculum from 1945 to 1980, and ends with a few words on the current status of the school today.

The Early Years

In 1917, the University of Washington (UW) created the School of Business Administration due to overwhelming demand from the Northwest business community, who probably recognized the need for well educated business personnel in the growing pacific economy. The schools first Dean was Professor Carlton Parker from the University of California, who fit then UW President, Dr. Henry Suzzallos, profile of “an alert, vigorous man to start a school of commerce, one who has practical experience and sense as well as scholarly training”. Carlton Parker was highly regarded in the business community as a business educator with one of his references, WJ Patterson, who was a manager of Hayes and Hayes Bankers of Aberdeen Washington crediting him with “stir[ing] the student body of the University of California to thinking than any professor in the college”. Together Dean Parker and President Suzzallo were able to recruit 7 instructors who came from Harvard, Stanford, and Wisconsin to teach in the first year of the business school, which had a student population consisting of only 12 undergraduates.

Instead of being integrated as a department within the college of arts and sciences, the School of Business Administration was its own separate college. The business school was combined with the economics department which was removed from the arts and sciences, and on March 14, 1919 the School of Business changed to the College of Economics and Business Administration to appropriately fit the department. The college had its own entrance requirements and four year program, to encourage students who took business courses during high school to go to the university even though they couldn’t enroll into the college of arts and sciences. And to compensate the students for the potential lack of a liberal education, the business curriculum provided a mix of both business and liberal arts and humanities classes. So along with courses in accounting and statistics, students also took classes such as general psychology and philosophy.

The study of business administration was a growing discipline at the UW. Two years after the inception of the business school, business majors accounted for 33 percent of the 2700 freshman that were enrolled in the university in 1919. This meant that business administration was the most popular major on campus, which was not surprising since the Board of Regents in it’s 16th Biennial Report said that it “ranked among the four leading Schools of Commerce in the United States” (Wheeler, 7). And in 1921 the College became a member of the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), becoming an accredited national school of business; its curriculum and quality of instruction considered to be in equal standing with other business schools from elite universities such as Harvard, Columbia, and Dartmouth – the business schools who created the AACSB. The College of Business Administration was only four years old and already it was one of the top institutions for business education in the country. This was definitely quite an achievement.

The Long Road to Improvement

As the years went by, the undergraduate business major continued to be the popular major at UW, with 40 percent of these majors specializing in accounting which was the most sought-after field of study. (To clarify – business majors are awarded a BA in business administration with a notation on their diploma stating their specialization.) Thus, the business schools undergraduate program was well established. On the other hand, the graduate business program was not nearly as desired by students or as well organized as the undergraduate program. The Masters of Business Administration (MBA) was a highly specialized program of study aimed exclusively at business majors. The problem with the program was its lack of both structure and solid course requirements for students to follow. The courses that were offered to fulfill the degree were haphazard in subject matter, with nothing in common. Recognizing the apparent deficiencies in the program, many graduate students opted not to finish their degree and dropped out.

The University of Washington attracted many highly regarded academic instructors to its faculty in the late 1940ís, which gained the UW a noteworthy reputation in the US as a distinguished institution. While the university appealed to many academic professors, research was not significantly substantive within the schools of the UW. Business school faculty were more attracted to business consulting, and textbook writing for monetary gain. And with the UW undergraduate business program as the most popular major, making it “one of the nations largest” (Schlossman, 4) of its kind at the time in late 1940, the business school faculty was faced with the student/teacher ratio of 50 to 1 – the highest compared to other faculty at the university. Research would just increase the stress already upon them, and many were concerned that it would take them away from their students and side projects. Thus when the UWs central administration, wanting to follow the academic trend of research at other prominent universities, decided to make research a priority for faculty advancement; the business faculty was greatly upset.

In 1948 the College of Economics and Business Administration split apart, due to long-term internal fighting between the two faculties. Thus, the name College of Economics and Business Administration was changed to College of Business Administration, and the economics department reverted back to the college of arts and sciences. Also in that same year a new dean, Austin Grimshaw, was appointed to the business school. Austin Grimshaw was a Harvard doctoral business graduate who “had a distinguished career at the University of Illinois…one of the nations most self-consciously research-oriented public universities” (Schlossman, 4). With his background, it was not surprising that Dean Grimshaw wanted to push research into the forefront of faculty priorities. And those who did not comply with research requirements, did not get salary increases nor were they promoted. So due to Dean Austin Grimshaws alleged abuse of his “power over salary, promotion, appointments, and course content” (Schlossman, 6), a mini-revolt insued by the faculty in 1959. This led to the formation within the business school of the Faculty Council. The Faculty Council substantially reduced the Deans power, because the business school faculty now had leverage over their curriculum and employment.

The issue of research requirements progressed at the University of Washington, with the appointment of Charles Odegaard as president of the university in 1958. Like Grimshaw, Odegaard greatly favored research which he thought was better than teaching and outside money-making projects. President Odegaard had an ambitious plan to make the UW’s “graduate and professional programs [in] line with the most advanced pedagogical thinking and research focuses of their fields” (Schlossman, 5). Eager to be part of this modernization plan Dean Grimshaw wanted to push the College of Business Administration, its undergraduate and graduate programs, in the throws of overhauling and reorganization. A task which would become controversial in scope, considering the business school faculty was not about to accept these changes without a fight. While the faculty realized the need for restructuring the business curriculum, they were adamant about having a strong voice over what changes would be agreed and disagreed with in their curriculum. To make the modernization of the business school happen; a united front consisting of the faculty, Dean Grimshaw, and President Odegaard was needed before it could begin.

One more obstacle would come between them before any serious revisions occurred. In June 1959, President Odegaard decided that the intense reorganization of the business school would require an associate dean, Kermit Hanson, to help with the planning. The faculty, believing that a possible conspiracy was taking place, regarded this appointment as an attack on their decision-making power. These feelings were resolved or at least calmed down, at a meeting between President Odegaard and the faculty. President Odegaard addressed not just the issue of the long-term affects of a growing student population on the College of Business Administration, but problems “stemming from the examination of objectives, educational philosophy, and qualifications for teaching careers in business” (Schlossman, 7). With their grievances aired and acknowledged, the faculty was now willing to begin reforming the curriculum.

While it was a long and hard road, the efforts of all three parties paid off. The early 1960’s saw a huge enrollment increase for the UWs business graduate program. Instead of offering the extremely specialized MBA program of the past, the new MBA program stressed the business enterprise as a whole and was aimed at administrators instead of specialists. Graduate students who wanted to specialize in business fields, could get a Masters of Arts (MA) degree instead. Also offered at the business school was the Doctor of Business Administration (DBA which was later changed to Ph. D) awarded to those students interested in “professional business training for teaching, research, and administration” (Wheeler, 15).

Many other notable changes went on at the College of Business Administration in the 1960ís. 1964 brought about the succession of Kermit Hanson from associate dean to dean; whos first task was to create an official graduate school of business, distinct from the undergraduate school of business where the graduate programs were residing. Dean Hanson wanted to do this in order to attract corporate, government, and foundation funds for faculty recruitment, student scholarships, and most importantly research. The Board of Regents agreed with “establishing…a Graduate School of Administration,…effective September 1, 1965” (Olswang, 1). And to invigorate the relations with the business community, Dean Hanson created the Board of Affiliates who were financial contributors to the graduate school of business, and an Advisory Council made up of corporate leaders. The business communitys involvement would definitely benefit the grad school by helping with business research, funds, and (of course) reputation.

Another major change came on December 17, 1965 when the business school changed its name back to School of Business Administration, in order to reflect a new change which would be implemented autumn quarter 1966 – the dismantling of the four-year undergraduate business program and becoming “a two-year upper division school” (Olswang, 1). In a memo from L.D. Goldberg to the business school faculty, several reasons for the change was to allow incoming freshman, who were previously enrolled into the business school during their first year, more time to choose whether or not majoring in business was right for them. The university wanted first year students to experience all the different fields of study offered at the UW, before they became committed to a particular major. Thus business majors were first enrolled in the college of arts and sciences (something they could previously by-pass), and at the end of their sophomore year they would need to apply to the business school before they could become recognized business majors. The second reason for becoming a two year program, was to ease the transition for transfer students from community colleges and other four year universities and colleges to the UW business program. With the School of Business Administration now more accessible to students than ever, an admissions ceiling was put on the school only allowing 1400 students a year in the early 1970’s.

Today the business school is still a two year program, admitting students in fall quarter only. It is still a popular major, with many students applying year after year; however, only a select few are accepted. All applicants have to take a test which consists of an essay to judge the students writing skills, and a video test where students fill out a multiple choice exam sheet which evaluates reactions to everyday business situations. All applicants must have at least a 2.5 cumulative grade point average, but usually the combined grade point average of accepted students is between a 3.5 – 3.7. While most students that are accepted to the business school are usually juniors (Upper Admissions Group) , the school still allows freshman to declare themselvesofficial business majors in a program called the Early Admissions Group.

The School of Business Administrations undergraduate program curriculum consists of required business courses which make up 39 to 40 credits needed for a BA, with 15 to 27 (only for accounting majors) credits in upper division business electives which make up the concentration that the student wishes to specialize in. These areas of special concentration are: accounting, business economics, finance, human resource management and organizational behavior, information systems, international business, marketing, operations management, organization and environment, and quantitative methods. Each course is demanding in order to adequately prepare the student for the real business world that awaits them after they receive their degree.

Conclusion

The School of Business Administration at the University of Washington, continues to be ranked among the top public business programs for both undergraduate and graduate education. The U.S. News and World Report in their September 1995 issue ranked the UWís business school #16 out of the top 50 programs that they surveyed. And many business school alumni have become famous public figures: Former Governor Booth Gardner, musician Kenny G. (an accounting major), Japanese House of Representative member Toshitsugu Saito, and many other UW business graduates who are leading distinguished careers in business, government, and other endeavors. By examining the history of the School of Business Administration, from its strong start under the guidance of Dean Carlton Parker and President Dr. Henry Suzzallo, providing the foundation what would allow the deans who followed Parker to build an enduring institution which continues to be at the top of its educational field.

Works Cited

Dr. Henry Suzzallo to WJ Patterson, 5 May 1916 Box 115/2, Carlton H. Parker Correspondence 1925 – 33 Acc. 71 – 34 University of Washington Libraries

Schlossman, Steven, Michael Sedlak, and Harold Wechsler. “Conflict, Consensus, and the Modernization of Graduate Business Education: The Case of the University of Washington, 1945 – 1980. Part 1: The Emergence of Reform Sentiment, 1945 -1963.” _Selections._ Winter 1989: 1-11.

Steven G. Olswang to Colleagues, 2 Mar. 1990 Box 9 Acc. 91-133 University of Washington Libraries

WJ Patterson to Dr. Henry Suzzallo, 13 April 1916 Box 115/2, Carlton Parker Correspondence 1925 – 33 Acc. 71-34 University of Washington Libraries

Wheeler, Bayard O. “The Golden Anniversary of the School of Business Administration, University of Washington.” _University of Washington Business Review._ Autumn 1967: 5-28.

Bibliography

Dr. Henry Suzzallo to Miller, 15 Mar. 1919 Box 115/3, Business Administration (Business Administration Colleges) 1918-21 Acc. 71-34 University of Washington Libraries

Gates, Charles M. 1961. _The First Century At the University of Washington 1861-1961._ Seattle: University of Washington Press.

LD Goldberg, Council Chairman memo to Business Administration Faculty, 12 Nov. 1965 Box 6, School Concepts Folder Acc. 81-57 University of Washington Libraries

Schlossman, Steven, Michael Sedlak, and Harold Wechsler. “Conflict, Consensus, and the Modernization of Graduate Business Education: The Case of the University of Washington, 1945 – 1980. Part 2: Stabilizing Reform and Maintaining Consensus, 1963 – 1980. _Selections, 1-9

University of Washington Undergraduate Program in Business informational packet for business student applicants

Second Vasquez Paper:

English 281 C

Azalea Vasquez

Assignment 4

3/16/98

One Among Many: Why the UW is an Example of an American University

Since the University of Washington is and has been one of the top public universities in the country, it is only logical to assume that its history is very similar to the histories of other public universities in the US; thus, the UW could be called a typical American university. Read any newspaper and/or educational journal, and watch any nightly news program; there’s a high likelihood that news items about the state of the university or anything to do with the country’s universities is reflected in some aspect of the UW. To be more specific about the similar issues that are shared by most universities in the US; a discussion of what has been going on in the areas of funding, research, and the ethnic diversity of the student population, and examples from the University of Washington’s past and present history explains why the UW is a typical American university.

The decreasing amount of public funding, and the increasing amount of private funding of universities has been a growing concern in the public for some time now. The issue at hand is ownership, and thus control over the actions and educational mission of the university; which would change if funding from corporations is more than the contributions from the public. The University of Washington is not exempt from this subject, which is evident when walking around the campus and seeing the names on buildings: the (Paul) Allen library named for the co-founder of the computer software conglomerate Microsoft, the soon-to-be constructed Mary Gates Hall named after the mother of the other Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, and the Seafirst Executive building named after the Seafirst Bank.

When a university is publicly funded (or rather owned) it is implied that the administration, and more directly the deans of the departments and schools and the professors in them, have control over the curriculum they teach and the research they choose to pursue. And what is further implied is that the public (as taxpayers and voters), can and are encouraged to voice their opinion about what is taught in the university; thus, ensuring that the zeitgeist of the society will be reflected in the curriculum. This is something that would not happen in a heavily corporate funded university.

The possible implications and consequences of corporate owned universities is the basis of J. Hillis Miller’s essay “Literary Study in the Transnational University”. In his essay Miller states that “a new kind of secrecy is invading our universities, the secrecy demanded by corporations as a quid pro quo for their support of research” (7). What is meant by this quote is that in order for universities to acquire corporate funding for research projects, they must not reveal who these corporations are to the public. This practice of not disclosing the identities of the corporate donors who fund these research projects is followed at the UW, and is commented on in Ana Rosen’s essay “Research Funds and the Route that Universities are Taking in Corporate America”. When trying to investigate funding at the UW, the details of “some of these gifts (funds) are restricted and unrestricted….[and] the vast majority of gifts received by the University of Washington are restricted….[but] “unrestricted” gifts…are considered restricted gifts for reporting purposes” (Rosen,2). All this mystery definitely makes one suspicious, and maybe should make one concerned.

If a university is considerably more privately funded, there could be a scenario where corporations “tamper” with the curriculum and research conducted at universities, by only appointing professors who agree with the corporations ideas and philosophies. A fear Miller shares when he says that “research accomplishment will be more and more not the acquisition of new knowledge but productivity as defined by the corporations to whom the university is accountable…setting its priorities…because they will own a bigger…piece of it” (8). More likely than not, these “corporate” professors will be more into their “corporate” research, than the educational research conducted for intellectual advancement, for the sake of the all mighty dollar. And to enable professors to conduct their research, corporations would lower the standards of undergraduate education, allowing professors to be apathetic to the curriculum and students because teaching is not their “real” job.

The subject of professors who conduct research and teach undergraduate education, with the question being which one of these endeavors should be the higher priority, is a problem universities are already faced with. Newsworthy research gives universities favorable reputations which increases their ranking among their peers, and allows them to attract sought-after academics to their faculty. However, there is a price to be paid for time consuming research; the expense of reducing the time and effort allotted to planning and conducting undergraduate education. In Dr. Paul Heyne’s essay “Researchers and Degree Purchasers: the Classroom Encounter”, he talks about how research affects the tenure of faculty at the University of Washington. Dr. Heyne states that “Almost all of the faculty appointments in the University are made on the basis of research potential, not teaching potential” (1). This means that the UW bases a professors worth not on their ability to educate students, but on how much research they have conducted and published. This kind of appointment system short-changes those professors who awaken the intellectual curiosity of students, by carefully planning out stimulating course material and who spend little time on research; and rewards those who obviously have not regard for quality education, but have plenty of published writings in journals. Thus one can only conclude that research is more important than undergraduate education at the UW.

Another indication that research is the main focus of the University of Washington is the Office of Technological Transfer (OTT), which is the subject of Peter Prescott’s essay entitled “Office of Technology Transfer: What, and Why”. Prescott explains that the OTT is “an entity that could work with faculty, staff and students to realize and follow through with the commercial potential of their technologies” (1). Or in other words, help the faculty, staff, and students market their inventions for money. And like any other agent or negotiator, they receive a percentage of the profits in the invention is a success. For example, Prescott reports that in 1994 the UW generated “a 54 million-dollar revenue” (3) from the inventions they helped to market. And in a time of decreased public funding, the money-making opportunities provided by research cannot be passed up. There was a time, however, when parts of the faculty at the UW was not receptive to the subject of research or making it a requirement for professional advancement. In my essay “A Brief History of the UW’s School of Business Administration”, the section called The Long Road to Improvement focuses on a time period when the business faculty was at odds with conducting research. Austin Grimshaw was the Dean of the College of Business Administration in 1948, and “wanted to push research into the forefront of faculty priorities” (Vasquez,3). Dean Grimshaw was supported by then UW President Charles Odegaard, who “greatly favored research which he thought was better than teaching” (Vasquez,3). The business school’s faculty was against research, because they felt it would shift their focus away from their students and textbook writing. The faculty’s opposition of research was so great that they started “a mini-revolt” (Vasquez,3) against Dean Grimshaw in 1959. A disgruntled faculty who are against research no longer exists at the current School of Business Administration, where many of the business faculty proudly show-off their work in educational as well as business journals.

The last example of an issue that the University of Washington shares with other universities, is the gradual diversification of the student and faculty population. In Louis Menand’s essay “What are Universities For?”, he writes that there has been a “major democratic change in the undergraduate population over the last twenty years…a significant increase on most campuses in the proportion of students who are not white” (93). In the past, universities were strictly for the sons of Anglo-Saxon middle- and upper-class families, but after the inception of the GI Bill and affirmative action the universities were open to people of color as well at women and poor people.

Michael J. Bennett’s book, When Dreams Came True, he talks about how the GI Bill affected the American university system. After World War II was over thousands of young soldiers came back home to America. The Government was worried about what thousands of unemployed and unskilled soldiers would do to the economy, so they decided to pay for their education so they could be absorbed back into the work force. Since the government was footing the bill many universities accepted the soldiers with no regard for their ethnicity, race, or social status, “With hundreds of thousands of veterans knocking on college doors seeking admission, discrimination could no longer be tolerated, if only for the practical reason that those applicants came prepared to pay with checks from drawn on the U.S. Treasury” (Bennett, 247). Thus the once unreachable dream of a university education was now attainable for people of color. In Janelle Cordero’s essay “Changes in the University of Washington through Affirmative Action”, she states that ìn 1965…[UW’s] President Odegaard, “appointed a faculty-administration committee on special education programs…to attract minorities” (2). So in compliance with what was going on in society and at other universities during this time, and to protect themselves from lawsuits; the UW decided to make an effort to enroll more minority students.

Another step the UW took toward striving for campus diversity, was the creation of ethnic studies courses that were added to the general curriculum. In Jennifer Wannarachue’s essay “History of the American Ethnic Studies Department” she explores how the department was created at the UW. Like all issues about race, the inception of ethnic studies was surrounded by controversy. The UW only created their first ethnic courses when “students first demanded a Black Studies curriculum in the Spring of 1968î (Wannarachue,1). Soon to follow were Asian American Studies, American Indian Studies, and Chicano Studies. Ethnic studies were not just offered at the UW, but at many other universities in the 1970ís due to the backlash of the Civil Rights Movement. And today most major universities have an Ethnic Studies department, just like the UW. By knowing more about the funding, research, and ethnic diversity at the University of Washington; we find that the issues surrounding these three matters, are the same ones faced by other universities. While the UW is supported by a larger amount of public funds than other universities, corporate funding and the ownership of the UW could be a problem if we were to lose the support from the public. Like all research universities throughout the country, the UW administration is trying to balance the needs of students with the needs of research. If this balancing act fails in favor of research, the quality of undergraduate education will suffer greatly. And as the US population becomes more and more diverse, the student population at our universities are becoming just as diverse; which is evident by walking around and seeing the different ethnic students enrolled at the UW. The University of Washington is definitely an example of a typical American university.

Work Cited

Bennett, Michael J.. When Dreams Came True: The GI Bill and the Making of Modern America. Washington: Brasseyís, 1996.

Cordero, Janelle. ìChanges in the University of Washington through Affirmative Action.î English 281 Website. (6 Mar. 1998).

Heyne, Dr. Paul. ìResearchers and Degree Purchasers: the Classroom Encounter.î The Online Daily of the University of Washington 29 September 1997. (5 Jan. 1998).

Menand, Louis. ìWhat are Universities For?î Falling into Theory. Ed. David H. Richter. Boston: Bedford Books, 1994. 88-99.

Miller, J. Hillis. ìLiterary Study in the Transnational University.î Profession 1996: 6-13.

Prescott, Peter. ìOffice of Technology Transfer: ëWhat, and Whyí.î English 281 Website. (6 Mar. 1998).

Rosen, Ana. ìResearch Funds and the Route that Universities are Taking in Corporate America.î English 281 Website. (6 Mar. 1998).

Vasquez, Azalea. ìA Brief History of the UWís School of Business Administration.English 281 Website. (6 Mar. 1998).

Wannarachue, Jennifer. ìHistory of the American Ethnic Studies Department.î English 281 Website. (6 Mar.1998).