The Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe

A Distinguished English Family Descended from a

Grimshaw Woman

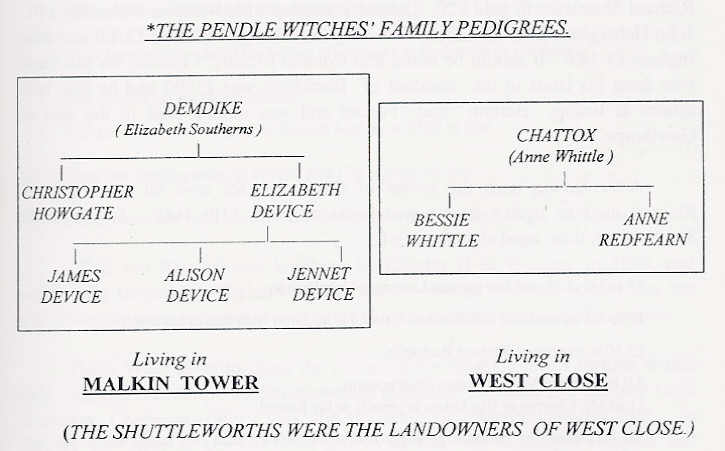

The Grimshaw arms, a black left-facing griffin, is depicted in Gawthorpe Hall

Anne Grimshaw was the fifth child of Thomas and Margaret (Harrington) Grimshaw of Clayton Hall. In 1540 she married Hugh Shuttleworth of Gawthorpe, located about four miles northeast of Clayton Hall. The descendants of Hugh and Anne (Grimshaw) Shuttleworth comprise one of the more distinguished family lines of Lancashire. Gawthorpe Hall, a significant historical landmark in the region, was built by the sons of Hugh and Anne between 1600 and 1604.

Contents

Descendant Chart and Coat of Arms

Hugh and Anne (Grimshaw) Shuttleworth and Family

Construction of Gawthorpe Hall and Life at the Hall

Evidence of Grimshaws in Gawthorpe Hall Artifacts

Shuttleworth Connections to the Pendle Witches

Detailed Pedigree Information from Harland

Shuttleworth and Gawthorpe Hall History by Tori Martinez

Charlotte Bronte at Gawthorpe Hall

Gawthorpe Hall, Now a British National Trust Property

Murray Shuttleworths Website on the Shuttleworth Family

Winston Churchill, 11th Generation Great-Grandson of Anne Grimshaw and Hugh Shuttleworth

Detailed Shuttleworth Descendant Chart from Whitaker

Images from John Harland’s “The House and Farm Accounts of the Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe Hall”

Webpage Credit

Thanks go to Michael P. Conroy for his extensive research on the Shuttleworth family. Much of the information on this webpage is taken from his 1996 booklet1, “The Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe.” Thanks to Deborah Nouzovsky for bringing out the fact that Winston Churchill is descended from Hugh and Anne Shuttleworth.

Who Was Anne Grimshaw?

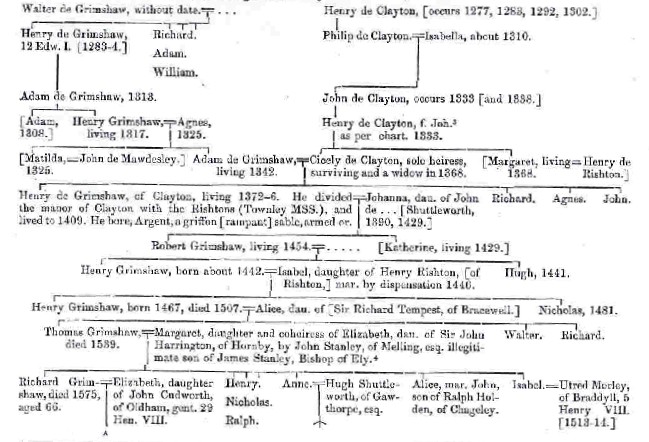

Anne was a member of the earliest known Grimshaw family line. As shown in the descendant chart in Whitaker2 (v. II, p. ___), Anne was in the llth generation after Walter Grimshaw, the originator of this ancient line of Grimshaws (see Figure 1 below.) It is described in a companion webpage. Anne was buried in Padiham in 1597. Annes brother, Nicholas, may have been the progenitor of the Pendle Forest line of Grimshaws, which is also described on a companion webpage, although it appears to be more likely that the Nicholas who was her grandfather’s brother (living in 1481) is the Pendle Forest progenitor. By the time Gawthorpe Hall was built in 1604 (seven years after Annes death), Clayton Hall had passed from her brother, Richard, to her grand-nephew, Nicholas.

Figure 1. Portion of descendant chart of Walter Grimshaw, head of the oldest known line of Grimshaws, showing Anne Grimshaw in the 11th generation (center of bottom of figure) after Walter. Figure is from Whitaker2, v. II, p. __.

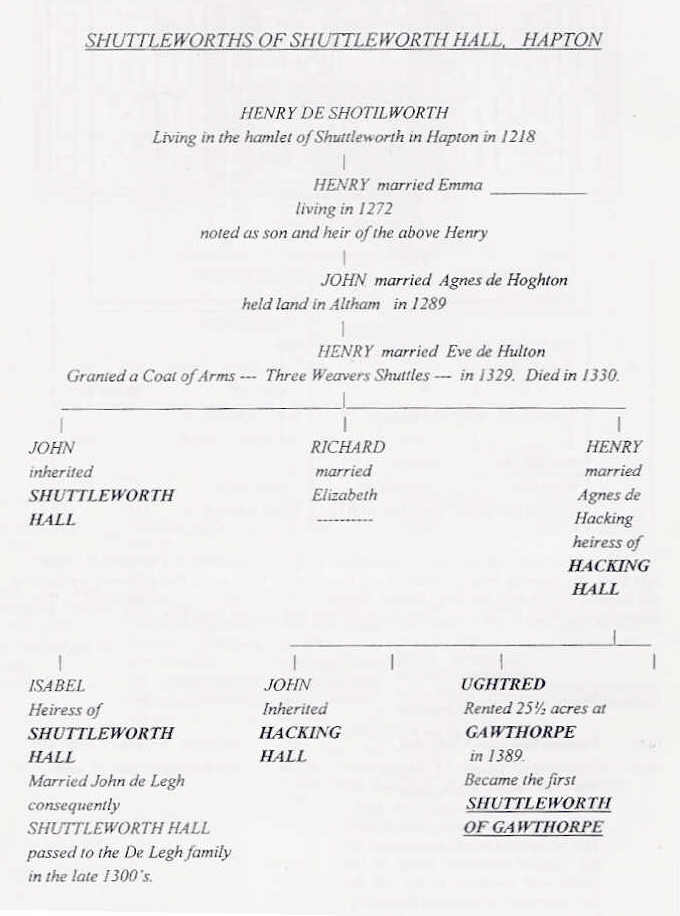

Shuttleworth Origins and Descendant Chart

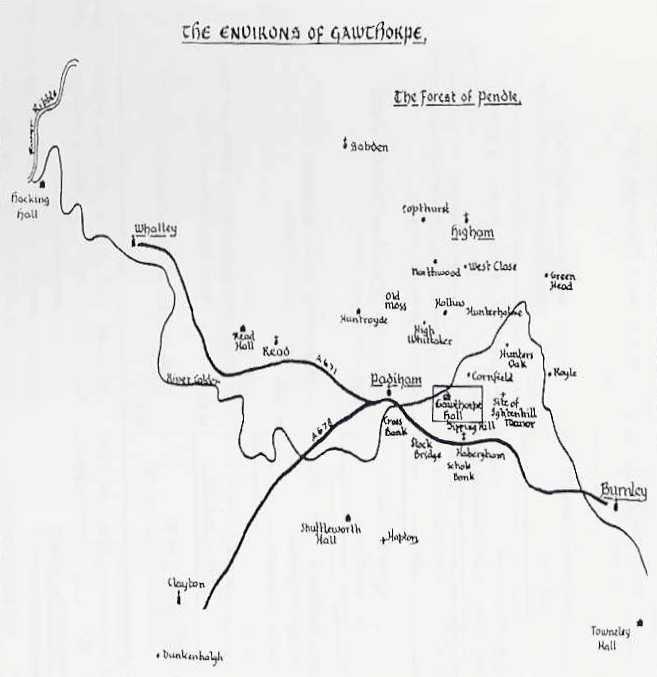

The earliest Shuttleworth on record was “Henry de Shotilworth” who was “living in the hamlet of Shuttleworth in Hapton in 1218” (Conroy1, p. 65.) Henrys great-grandson, also Henry, was granted the Shuttleworth coat of arms, with three weavers shuttles, in 1329. This Henrys son, again also Henry, was living at Shuttleworth Hall near Hapton (Figure 2) in 1325 – 1326. Shuttleworth Hall (Figure 2) is located southwest of Gawthorpe, about halfway to Clayton Hall, where the Grimshaw family resided (Figure 3.)

Figure 2. Shuttleworth Hall, location of the oldest recorded family of the same name. Photo taken May 1999.

(in preparation)

Figure 3. “The Environs of Gawthorpe,” showing the location of Gawthorpe near Padiham. Note also the locations of Shuttleworth Hall and Clayton (Hall) to the southwest of Gawthorpe Hall. From Conroy1, Fig. 2.

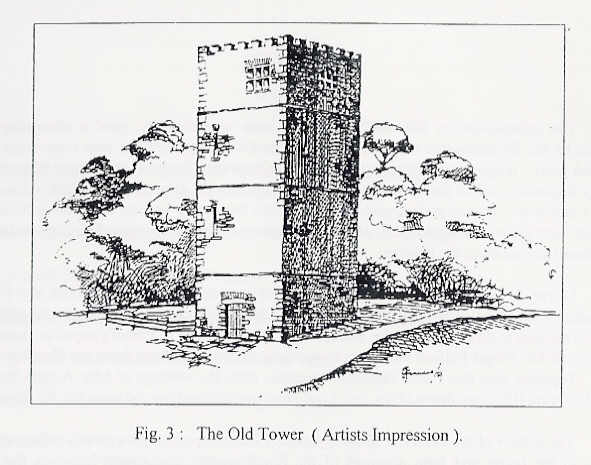

Henry Shuttleworths son, Ughtred, was the first Shuttleworth at the Gawthorpe location. Ughtred was living in 1388 – 1389. Just before, or during, Ughtreds life, a square watchtower of the Norman style was constructed at the Gawthorpe location (Figure 4.)

Figure 4. Artists impression drawing of the watchtower constructed at Gawthorpe in the first half of the 14th Century. From Conroy1, Fig. 3

An excellent summary of the Shuttleworth family history, including the earliest period, is presented in Conroy1 (p. 1-4):

THE SHUTTLEWORTHS OF THE TOWER

Ightenhill Manor was situated between Padiham and Burnley in North East Lancashire. In the time of the Plantagenets it was the administrative centre for an area stretching from Padiham to Marsden. When Edward the Second stayed there in 1323 he would find his equitium or horse breeding establishment there had been decimated by the raid that same year by the Constable of Skipton Castle. Coming some nine years after his disaster at Bannockburn he would certainly be looking at the defences in the area and a watch tower (fig 3) at Gawthorpe would doubtless receive his attention, situated by the river Calder at the western end of 1ghtenhill Manor Park. Certainly horses were again being reared there in 1342 according to the diary of the Keeper of the King’s horse breeding establishments, Edmund de Thedmersshe.

It is open to conjecture whether the watch tower was already in existence in 1323 or whether Edward decided to extend his defences in that direction after the raid. We do know that William of Gawthorpe gave up the nine and a half acres there in 1333 and the new tenant did not start farming it until 1342, could this have been because the tower was being built during the intervening time? Certainly the new tenant paid a reduced rental, perhaps this was due to the loss of acreage covering the area taken up by the tower and its environs?

During his visitation the King would probably meet the local gentry which included Henry de Shuttleworth from neighbouring Shuttleworth Hall (see page 65) whose son, Henry married Agnes the heiress of William de Hacking of Hacking Hall. (fig 1). It was Ughtred, one of their younger sons, who was the first Shuttleworth of Gawthorpe (fig 23). He arrived there during the period when John of Gaunt was Duke of Lancaster and, consequently the owner of the Manor of Ightenhill.

It would appear that the palisade that surrounded the park was now not necessary, which suggests that the horses and deer were no longer being bred there by this time. This was shortly before Ughtred Shuttleworth arrived at Gawthorpe. He was living there in 1389 and grew corn there during the following forty years. A Parchmcnt document, one of the earliest written in English with an East Lancashire dialect was found in the old estate office (fig 8). Written in the early 1400’s it testifies that Ughtred had then been at Gawthorpe some 40 years and had been sending his corn to Padiham Mill during this period. This petition had been written because John Parker at Ightenhill (and there was a John Parker at Ightenhill in 1425) had accused Ughtred of not sending his corn to the mill at Burnley. Ughtred prayed that he might continue to send his corn to the mill at Padiham, stating that as both mills were owned by the king (Henry VI.) the king would not lose by this. It would appear that Ughtred must have been producing a substantial amount of corn to warrant the attention of the steward of the Manor, eager to claim his ‘millsoke’ or tithe from the grain if it went to the corn mill in Burnley.

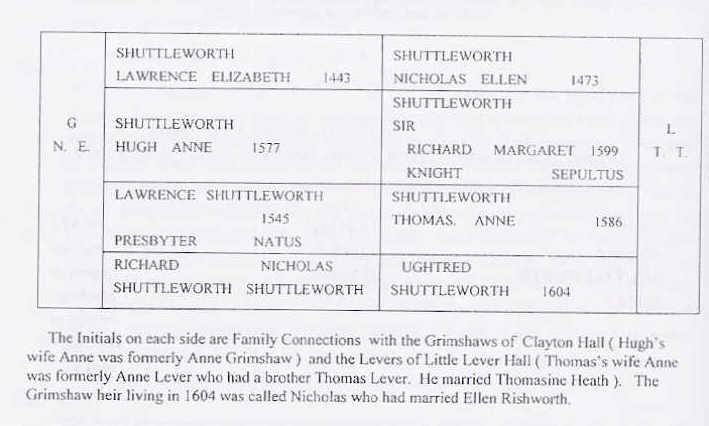

From the time of Ughtred’s descendant Hugh, who was living in 1463, we have a clearer picture of the family’s fortune for Hugh’s son Lawrence, the first name on the wooden plaque at Gawthorpe (fig 44) and with the date 1443 by his name (which could be his birth date) had married Elizabeth Worsley of Twiston, the grand-daughter of Henry Towneley of Bamside (Laneshawbridge). She was the co-heiress of her father Richard Worsley of Mearley and Twiston and shared these estates with her sisters. In 1507 Henry the Seventh had abandoned his policy of reserving land for the breeding and chasing of deer, thus great acres of deer forests were granted out for fixed rents; parts of these, including West Close, south of Higham, were released to Lawrence during this period.

Descendant Chart and Coat of Arms

The earliest known Shuttleworth was a Henry, who was living at Hapton in 1218. Conroy1 (p. 65) presents a descendant chart for “Henry de Shotilworth” (Figure 5a,) which extends for six generations and shows Ughtred as the “first Shuttleworth of Gawthorpe.”

Figure 5a. Descendant Chart of the earliest known Shuttleworth (Henry de Shotilworth), showing six generations.

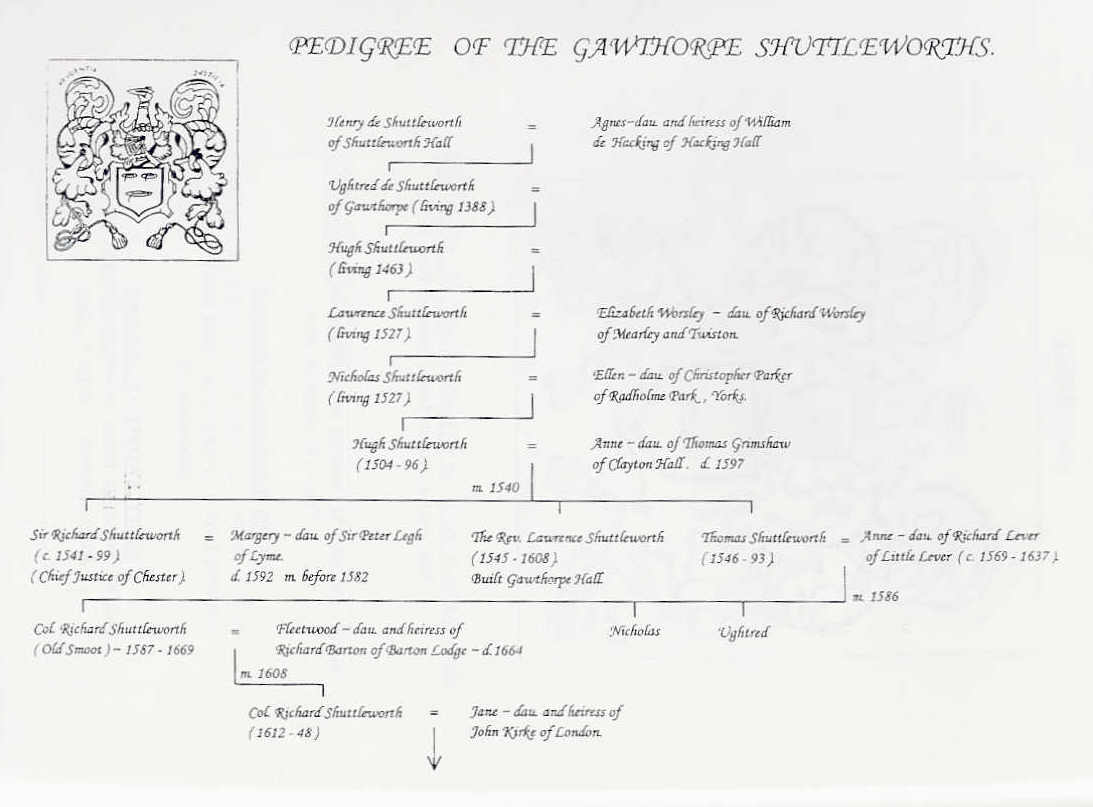

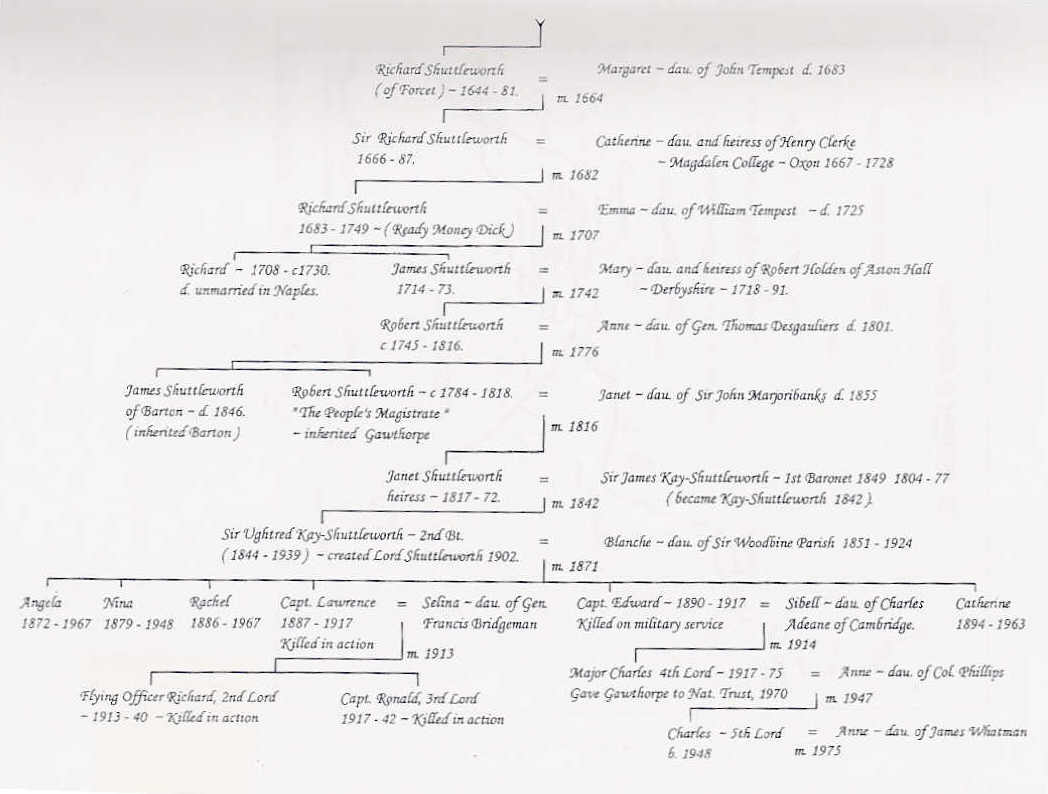

Conroy1 (front matter) picks up this descendant chart at the 5th generation (Henry, m. Agnes de Hacking, heiress of Hacking Hall) in another descendant chart that extends for another 20 generations (Figure 5b, in two parts.) Hugh Shuttleworth, the 6th generation descendant of Henry and Agnes, is shown as the spouse of Anne, daughter of Thomas Grimshaw. A more complete version of the Shuttleworth descendant chart from Whitaker2 is provided further down on this webpage.

Figure 5b. “Pedigree of the Gawthorpe Shuttleworths” from Conroy1 (Front Matter.) Note Hugh and Anne (Grimshaw) Shuttleworth, married 1540, in the middle of the upper part of the figure.

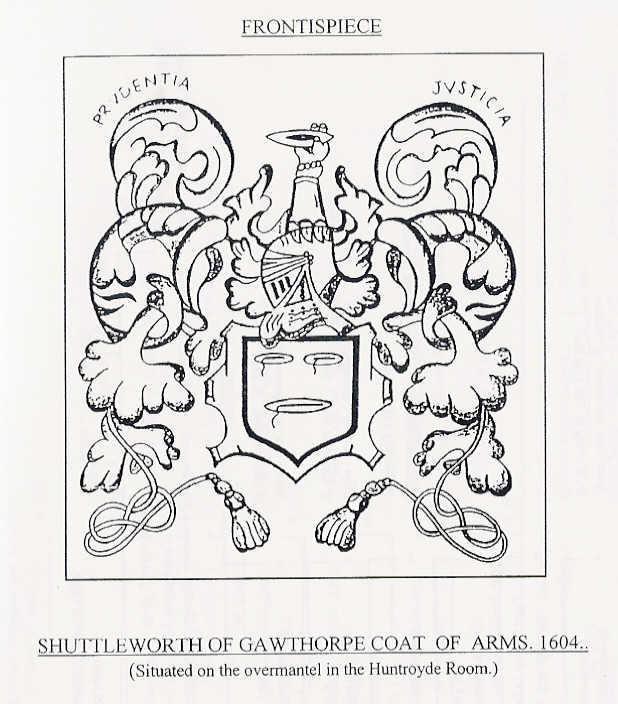

As noted above, a coat of arms was granted to the Shuttleworth family – to Henry Shuttleworth, 4th generation descendant – in 1319. This Henry was the father of the Henry who was living at Shuttleworth Hall in 1325 – 1326. The Shuttleworth coat of arms is characterized by Whitaker2 as shown below; a rendition of it is provided by Conroy1 and is provided in Figure 6.

Arms

. Argent, three weavers shuttles sable, tipped and furnished, or.

Crest. On a wreath of the colours a cubit arm in armour, the hand in a gauntlet proper grasping a shuttle, as in the arms.

Motto. Prudentia et Justicia.

Figure 6. “Shuttleworth of Gawthorpe Coat of Arms, 1604” as presented in Conroy1 (frontispiece), who notes that it is “Situated on the overmantel in the Huntroyde Room” (of Gawthorpe Hall.)

Gawthorpe Hall

Gawthorpe Hall was built in 1600 – 1604 by Lawrence, second son of Hugh and Anne (Grimshaw) Shuttleworth. The hall was constructed from plans that had been drawn up by Lawrences older brother, Richard, who died before he could implement the plans. Gawthorpe Hall was constructed by incorporating the previously existing watchtower, which had been build 250 hears earlier (Figure 7.) Details of the construction of the hall are provided further down on this webpage.

Figure 7. Gawthorpe Hall, eastward view. Note the extension (by more than two stories) of the watchtower, around which the hall was built, above the main structure of the edifice. Photo taken from the internet at the website shown below the figure.

Hugh and Anne (Grimshaw) Shuttleworth and Family

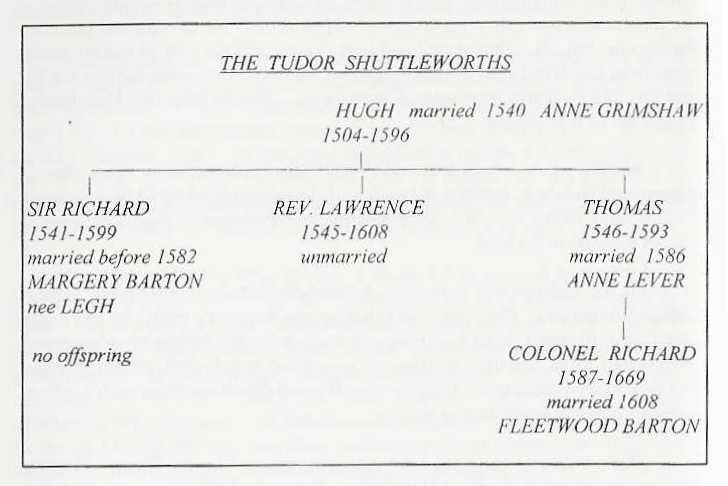

Hugh and Anne and their family apparently started the Shuttleworth family down the path of distinction. They had three sons – Richard, Lawrence and Thomas (Figure 8a.)

Figure 8a. “The Tudor Shuttleworths.” From Conroy1, p. 10.

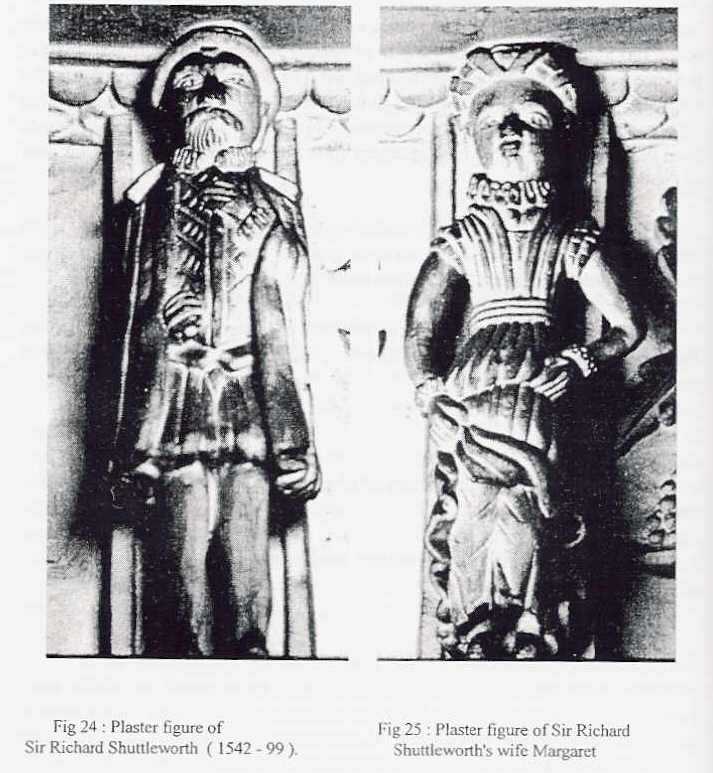

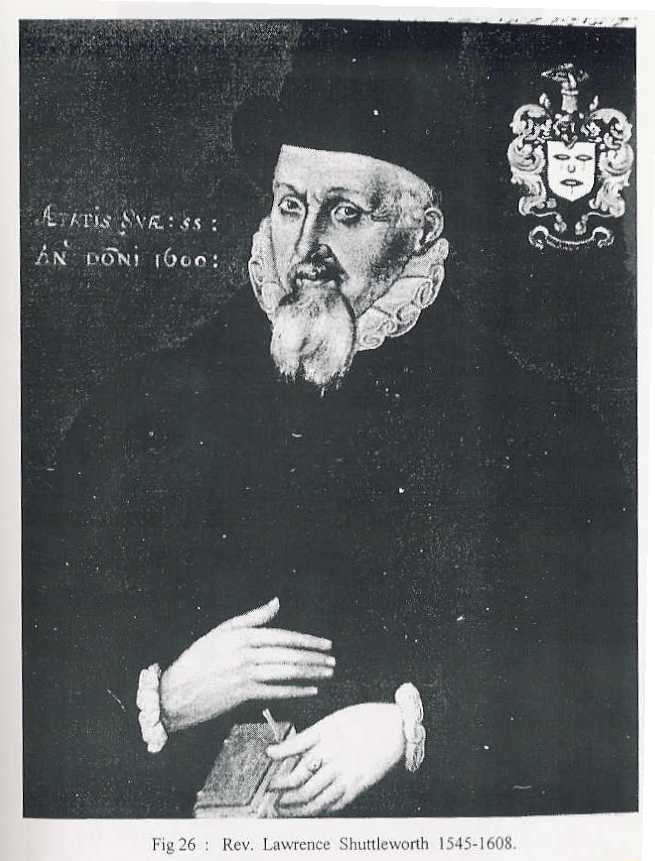

Gawthorpe Hall was planned by Hugh and Anne’s oldest son, Richard, but was actually built by their second son, Lawrence. Plaster figures of Richard and his wife still exist in Gawthorpe Hall and are shown in Figure 8b. An image of Lawrence Shuttleworth is presented in Figure 9. The Grimshaw arms is depicted in Gawthorpe Hall with the arms of other families that “married into” the Shuttleworth family (Figure 10.)

Figure 8b. Plaster figures of Sir Richard and Margaret (Legh Barton) Shuttleworth. The figures are “to be found above the Drawing room” according to Conroy1 (Figs 24 and 25.)

Figure 9. Reverend Lawrence Shuttleworth. From a painting in Conroy1 (Fig 26.) Note the Shuttleworth coat of arms in the upper right corner.

Figure 10. The Grimshaw arms, a black griffin facing left, is presented (along with the arms of nine other families) at the main entrance to the Long Gallery of Gawthorpe Hall. From Conroy1, Fig 52.

Conroy1 (p. 5-7) provides a great deal of information on Hugh and Anne Grimshaw and their descendants; it is provided below (underlines added by website author):

Lawrence’s son Nicholas married Ellen Parker of Bowland daughter of Christopher Parker of Radholme Park in Bolland (Bowland), another notable t3mily in the area. (It was her cousin, Edmund, who built Browsholme Hall in 1507 where the Parkers still reside.). Nicholas’s date on the plaque is 1473. He it was who covenanted with the Towneleys and others for the rebuilding of Burnley parish church in 1532. Their son, Hugh was twenty-eight by this time having been born in 1504. He married Anne Grimshaw of Clayton Hall in 1540. The Grimshaws held the manor of Clayton and had important connections, Anne’s mother Margaret being a member of the Stanley family. Hugh and Anne had three sons, Richard born 1542, Lawrence born 1545 and Thomas born about 1546. Hugh Shuttleworth was now affluent enough to provide 28 soldiers in the muster of 1574. In the next decade his son, Richard received the honour of Knighthood, probably when he was elevated in the judicial bench. In 1580 the Shuttleworths acquired the lease of Ightenhill Manor Park, some 690 acres to the east of Gawthorpe (the Manor House by then in ruins and had been since the 1500’s). Now the family had control of most of the land in the Padiham, Simonstone, Higham, Ightenhill and Habergham area. Thus the Towneleys and Shuttleworths were the most influential gentry in the area at this time, so much so that they were ‘chosen’ by Queen Elizabeth to lend money to the crown in the year of the Armada 1588, and again in 1597.

The house and farm accounts of the Shuttleworths for the years 1580 to 1620 have been preserved and give a fascinating insight to the building of Gawthorpe Hall and the life of its inhabitants during that period in which the old Tower was transformed into the new Hall (fig 5).

THE BUILDERS OF THE ELIZABETHAN HALL.

The forty years 1580-1620 include the last twenty three of Elizabeth’s reign and the first seventeen of the Stuart Dynasty in the person of James I (fig 48). They were years that saw the defeat of the Spanish Armada and the many struggles involved in the conquest and settlement of Ireland; while, during James reign, Lancashire was “honoured” by a royal visit.

In her excellent paper on the Gawthorpe records, Miss E. Foster stated that …the four Shuttleworths of this period whom we must know in order to follow the story of the building of the Elizabethan Gawthorpe (fig 6) represent four distinct stages in growth of the family fortunes. First came Mr. Hugh Shuttleworth, of Gawthorpe, already 78 years old in 1582, but destined to live to the ripe old age of 92 before he was buried in Padiham. The chief feature of the Gawthorpe of his day was the “peel” tower (fig 4).

There were many such strongholds in the hilly districts of the Northern counties in the Middle Ages, consisting of little more than a square stone tower, uncomfortable dwellings of local gentry and temporary refuges for their tenants during periods of rebellion and border raids, for Scottish inroads sometimes penetrated as far south as Lancashire. The original tower was late incorporated in the Hall but one should think of the building at first as something very much like a square Norman keep and of the family as landowners on the Ightenhill side of Burnley, already connected by marriage, in one or other of their branches, with the Worsleys of Mearley and Twiston, the Towneleys, and the Parkers of Radholme and Bolland (Bowland).

It was under Hugh Shuttleworth’s eldest son, Richard, that the wealth and prestige of the family increased even more with his acquisition of estates at Inskip, Barbon and Forcett. He was a successful barrister, who became a Sergeant at Law in 1584, when he was about 43 years of age. Later he was created Chief Justice of Chester, and also held an appointment in the House of Lords, some professional position involving legal knowledge in the preparation and revision of Bills. He was knighted for his services seven years after the commencement of the published Accounts. His Parliamentary and professional duties must have made him a busy man. Often kept in London, either at the House or Westminster Hall and regularly on circuit in Cheshire, he must have spent little time in Lancashire, and less at Gawthorpe, for when he married the widow of Mr. Robert Barton, of Smithills, he lived on her property at Smithills, near Bolton, adding considerably to that and to his own Gawthorpe lands by purchasing other estates. His mode of life was scarcely altered by his inheritance of Shuttleworth lands on his father’s death in 1596. Smithills remained the business centre of his property, his agents living there. (They were his brother, Thomas, until his death in 1593 and then his other brother, Lawrence.) It was unlikely that such a successful man as Sir Richard would neglect his ancestral home entirely. Indeed, during the latter part of his life he was planning a restoration and extension of Gawthorpe, which was, however, not destined to be accomplished till after his death in 1599. It has been suggested by Dr. Mark Girouard that the architect was Robert Smythson, architect of Longleat.

Sir Richard did not have any children. Smithills reverted to the Barton family and Gawthorpe passed to his brother, Lawrence Shuttleworth, B.D., a man in his middle fifties. For seventeen years he had been Rector of Whichford in Warwickshire, a living in the gift of the Earl of Derby, which he owed very probably to his brother’s influence. Although he remained in the Church, and died and was buried at Whichford eight or nine years later much of his time must have been diverted from his calling, for he had succeeded to his brother Thomas’ stewardship on the latter’s death in 1593. His clerical training stood him in good stead, for the Gawthorpe and Smithills accounts were kept much more methodically by him than by his younger unclerical brother.

During this phase of his life his time must have been divided between Smithills and Whichford, and later between Whichford and Gawthorpe and the fact that he lost so little time carrying out his brother’s plans shows how intimately he had been associated with them. It is with him that we enter on the third of the four phases. Under Mr. Hugh Shuttleworth we saw the old Gawthorpe of the Middle Ages; then, under Sir Richard, came a time of increasing wealth, with plans to extend the family home until it should become a fit setting for their greater prestige. The third phase sees the re-modelling of Gawthorpe so that it becomes very much as we know it now. The bulk of the building was accomplished between the years 1600 and 1604, though the completion of the interior took longer; so the Rev. Lawrence Shuttleworth’s ownership coincides with the most absorbing period in the whole of the history of Gawthorpe Hall. Together with this, Lawrence extended the estate by buying more land in the areas of Padiham, Sabden and Burnley.

The fourth and last phase in this survey shows the head of the family in even greater prominence than any of his ancestors, for the name of Colonel Richard Shuttleworth is known to many who probably scarcely remember having heard of either Sir Richard or the Rev. Lawrence Shuttleworth. The nephew of both (the son of Thomas, one time steward), Colonel Shuttleworth became high Sheriff of Lancashire (1618 and 1638), and long after the time when the accounts close, he was destined to take an important part in the stirring events of the revolutionary struggle between Charles Stuart and his people. He represented Preston In the long Parliament, and was one of a special commission to organise Lancashire for war against the King.

It will be as well to mention that Gawthorpe was re-built at a period that saw the erection of many of England’s stately homes. The age of turbulent rebellions, characterised by the building of defensive stone castles, was over, peace, good government and commercial expansion under the Tudor monarchs led to a rapid increase in the number of country houses at a time when timber, used so long for houses, ship building, and fuel, was becoming scarce. Hence the greater use of stone for building in localities where it was quarried, and in others the erection of the brick and timber houses of the Midland and Southern counties.

Construction of Gawthorpe Hall and Life at the Hall

Conroy, taking extensively from Harland3, provides a lot of detail on how Gawthorpe Hall was constructed. Much interesting insight in how life was lived at the hall is also included. This interesting detail is shown below (p. 7-10):

Gawthorpe is built from local stone, quarried in the early part of 1600 and throughout the period of building, as it was required from “Ye stone delff at Gawthorpe”, Scholebank (Lowerhouse), Ryeclifft: (High Whitaker), and Padiham Moor. For getting stones at Ryecliffe a quarryman was paid at the rate of 6d a day. His work included squaring and rough-dressing or scappling the stones with a hammer, not a chisel, while the skilled mason who dressed window stones, lintels, etc., had 7d or 8d. Labourers received 2d or 2-½d. Wallers seem to have been paid at varying rates, sometimes by the day, sometimes by the yard. In connection with masonary it may be noted that it was a joiner, not a mason, who carved the coat of arms over the main door.

During August there is an entry in the Accounts “Roger Cockshotte, for 6 days fecings (Levelling?) the ground works for the new hall at Gawthorpe, le day, 2d.” and a further entry verifies the preparation of foundations, while on August 26, 1600, the first stone was laid, the occasion was celebrated by giving each workman, including six masons and ten labourers, the housekeeper, two maids and eight male work-servants. including the cowboy, money to buy a pair of gloves.

Meanwhile, the supply of timber had to keep pace with the requirements of building, for scaffolding, for a temporary stable to accommodate cart horses for flooring boards, for beams and for roofing. Most of the timber seems to have been got from Mytton and Read woods, and prices of trees and labour constantly occur in the accounts.

Lime for mortar and for manuring the lands was brought from Clitheroe, iron in square bars from Halifax to be worked by smiths at Gawthorpe into window bars, “dower neles”, locks and keys; while in November, 1602, there is an interesting entry that seems to point to Derbyshire as the source of the lead supply for interior and exterior plumbing and roofing.

These must have been years of bustling activity, for not only was building going on apace, but all sorts of subsidiary crafts were necessary. Sometimes there was a wheel-wright repairing carts and barrows, a smith shoeing horses, a saddler attending to harness, while carters were constantly employed in the transport of materials for building as well as farm necessities, food and clothing.

Rearing day (i.e. when the new Hall had been raised or reared so far as the roof), June 19, 1602, is marked by a special payment of 6d to a “pypper” who must have added his music to the general celebration. While the rooting of hall, barn (fig 14) and outbuildings was occupying a slater at 4d a day, a “Burnley smyth” was paid 3s.8d. “for one great locke for the haldower”, and a Clitheroe glazier was at work on the windows. 1603 saw the completion of a good deal of the interior plastering, including chimney pieces, friezes and ceilings; and in 1604 the supply of cupboards, tables, beds, and other furniture was begun.

In addition to re-building, the Rev. Lawrence Shuttleworth purchased lands in the neighbourhood of Padiham and Sabden, and seems to have developed his estate. His steward is a certain Edward Sherburne, who received 16s.8d. a quarter for his services. Farm accounts figure largely; there are men ditching, hedging, ploughing, sowing corn, weeding, reaping, and haymaking; women weeding and shearing sheep (3d a day), and a boy is paid 2d a day” for keeping crowes furth of wheat in Whittaker Ises”. A draught ox is bought for £3.3.4d. a ‘fat cowe’ in Colne for £4.4.0d, and amongst other purchases of farm materials are ropes and whipcords, riddles, sickles, scythes, reaping hooks, ploughs, ox yokes, leather for “flaylles”, lanterns, seeds and fodder, and tar to mark sheep.

The size of the household was already mentioned at the time when the foundation stone was laid. It included the housekeeper, two maid servants, and eight male servants (fig 20). Later it would be increased, for it is thought that Mrs. Thomas Shuttleworth, widow of the former steward and mother of the future Colonel Shuttleworth, lived at Gawthorpe in the absence of the Rector of Whichford. During the early days of building, the house-keeper was Jane Hodgkinson. She was succeeded in 1603 by Elizabeth Russelle, both of whom received 6s.8d., as a quarter’s wage. It was part of the house-keeper’s business to control the food and some of the clothing and we find her responsible for numerous purchases. She buys three stones of butter for 10s from “a wiffe in Symondstone”, honey by the quart, ten cheeses at a time, and barrels of herrings from Preston, barrels of ale, a load of malt from Halifax, hops, a peck of wheat, half a mutton, a fat cow, a fat bull, a fat ox from Clitheroe, a fat “stage” (Blackburn), and numerous spices about Michaelmas.

They burnt “colles”, but not so much as wood, and many white candles, though an item showing the purchase of candle “rishes” suggests that they also made some of their own. Household utensils include pewter and wooden spoons, baskets, bottles, drinking glasses, wash tubs, wooden vessels, metal pots or skillets, while a travelling tinker is employed to mend pots and pans.

Canvas is bought for making sacks and towels for workmen, and the cowboy is evidently fed and clothed, for on one occasion there is an entry showing the purchase of two calf skins and two “shippe skines” for doublet and breeches for the cow boy, 4s. They were lined with canvas, and the cost of making them, apart from the thread and buttons, was 6d. Two shirts were made for him for 2d, and his cloth stockings were cut and sewn for 2d. Miss or Mrs. Jane Hodgkinson earned her £1.6.8d. a year!

When we turn to such topics as dress, festivals and holidays, taxes, illness, doctors and burials, to mention only a few of the subjects that could be developed from a study of the accounts, what happens at Gawthorpe is typical of country houses throughout the land.

Of the fashions and materials of Elizabethan days, it is possible to find endless illustrations. The bodices of ladies’ gowns were very stiffly cut, and made on a lining of canvas, linen buckram, or even pasteboard. Grograine or grogram, velvet cloth, satin, “taffatie”, and damask were the materials used, and fur, ribbons and lace formed trimmings. Imagine Mrs. Richard Shuttleworth in such a gown, with full skirt and long hanging sleeves.

There are visits by “Lord Darbie his plaires”, and by the Queen’s Players, who on one occasion played at Gawthorpe. The sum of 3d was on one occasion paid to a poor piper. There are also payments in connection with the sports of hawking, and stag, deer and buck hunting, There are records of gifts to “poor scholars” and to poor men and women, and widows in their sickness.

Some idea of the methods of taxation can be gleaned from the Accounts. The common tax was the 15th part of the value of a man’s moveable goods. Originally it was levied by the monarch with Parliamentary consent, but in Tudor days it was applied to local taxation also. In 1620 Mr. Shuttleworth pays “two-fifteenths towards the Burnley clock”, which amount was fifteen pence. Fifteenths and multiples of fifteenths were levied for repairing churches, bridges and highways, for poor relief, for the provision of a cuck stool (ducking stool) for Burnley, and a house of correction for Blackburn, and for prison maintenance’.

Probably the wealth of detail relating to the vicinity of Gawthorpe that is included in the Shuttleworth documents has never been realised by the local communities of Burnley and Padiham. Small snippets of unrelated information connected only by their relevance to affairs at Gawthorpe are probably best understood by a glossary of details taken from the accounts. These items form a fascinating in-sight to the period between 1580 and 1620 and can be found as an appendix to this book.

The five important Shuttleworths mentioned in the ‘Accounts’ were all born in the Tudor era, the father Hugh in 1504, his three sons Sir Richard, Lawrence and Thomas in the 1540’s and Thomas’s son Colonel Richard in 1587. (See also Fig. 46). As influential members of the gentry they had many connections both in the vicinity of Gawthorpe and further afield. A number of these are mentioned in their accounts.

Evidence of Grimshaws in Gawthorpe Hall Artifacts

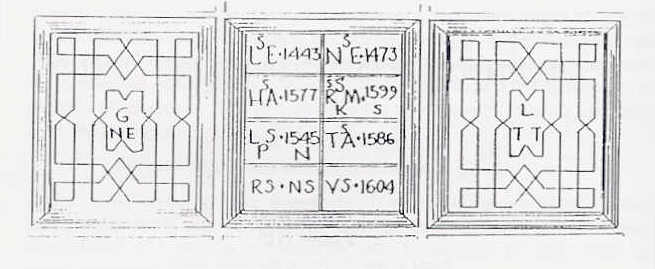

The Grimshaw connections to the Shuttleworth family is evidenced by artifacts that can still be found in Gawthorpe Hall. The most significant of these artifacts is the Entrance Hall Panel, which was installed by Lawrence Shuttleworth in 1604 when he build Gawthorpe Hall. The panel is shown and discussed in Figure 11 below; it depicts records of Hugh and Anne (Grimshaw) Shuttleworth and their three sons, Richard, Lawrence, and Thomas as well as later descendants. Reference is also made to the Grimshaw heir then living at Clayton Hall – Nicholas and his wife, Ellen (Rishworth) Grimshaw.

Figure 11a. The Entrance Hall Panel in Gawthorpe Hall (from Conroy1, Figure 44).

Figure 11b. Conroys interpretation of the initials and dates on the Entrance Hall Panel.

Figure 11c. Significance of the dates included in the Entrance Hall Panel.

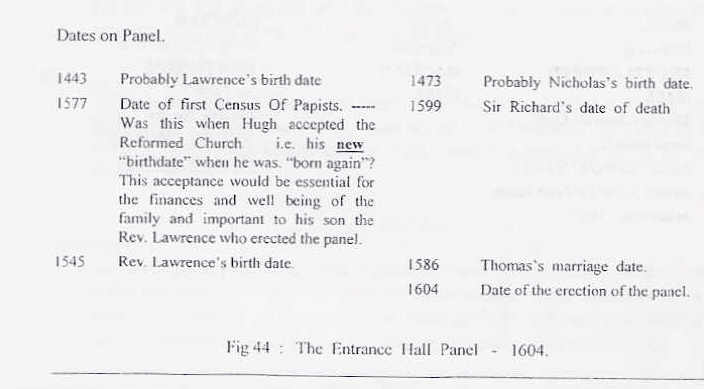

Shuttleworth Connections to the Pendle Witches

The unfortunate story of the Pendle witches, in which seven people (six women and one man) were put to death by hanging in 1612, is described in a companion webpage. The person who accused the women of being witches was Robert Nutter, the servant of Sir Richard Shuttleworth (oldest son of Hugh and Anne.) The accused witches, Chattox (Anne Whittle) and her daughter, Anne Redfearn, lived in West Close, which was owned by the Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe. The following excerpt from Conroy1 descirbes the events and connections. Figure 12 shows the pedigrees of the Pendle witches.

Robert Nutter from Greenhead Farm was a servant of Sir Richard who travelled with him when he went on his judiciary circuit in the area. As they returned through Cheshire after one of their visits to Chester in 1595 Robert complained to Richard that he had been bewitched by Chattox (the nickname

of Anne Whittle, one of the Pendle witches) just as his father Christopher Nutter had been bewitched by Chattox’s daughter Anne Redfearn in 1593, two years previously. Robert died in Cheshire and in 1612 Chattox was executed at Lancaster Castle for his murder, and Anne Redfearn, her daughter, was executed for the murder of his father Christopher. As Chattox and her family lived on Shuttleworth lands, at West Close, the Shuttleworths had to pay 6d as landowners for the transporting of Bess Whittle’s clothes to Lancaster in 1613. Bess was Chattox’ other daughter but she was not convicted of witchcraft. The clothes were her downfall for Bess had broken into Malkin Tower and stolen the best linen apparel from the Demdike brood, then was foolish enough to wear items of it at church on Sunday! She had been seen by Alison Device, granddaughter of Old Demdike (the nickname of Elisabeth Southernms) who reported her to Roger Nowell, the magistrate.

Figure 12 Pedigrees of the Pendle witches families (from Conroy1, p. 15.)

Detailed Pedigree Information from Harland

Conroy1 quotes extensively from Harland3 to provide additional information on the Shuttleworth family line. This information is provided below.

PEDIGREE OF THE FAMILY OF GAWTHORPE

(Quoting John Harland’s Notes In ‘The Shuttleworth Accounts.)

Henry Shuttleworth married Agnes, daughter and heiress of William de Hacking, (who was the great grandson of Bernard de Hacking) and thus brought those “states to the Shuttleworths, of whom a branch settled at Hacking A William de Hacking had a grant of Billington Mill from Henry de Lacy, prior to 1311, and was living early in the reign of Edward III. This Henry Shuttleworth was living 19th Edward II (1325-6). His younger son was:

Ughtred the first of that name on record, and Whitaker says (on what proof does not appear) the first of the family, of Gawthorpe. That a Ughtred was living l2th Richard 11 (1388/9) is shown by the entry from the court rolls of Clitheroe, which also shows that the Shuttleworths of that early period were holding land at Ightenhill, the Ightenhill so often referred to in the Shuttleworth Accounts.

Hugh of Gawthorpe, the name of whose wife has not been preserved, but he was living in the 3rd Edward 4th (1463/4) and his son and heir was

Lawrence of Gawthorpe who married Elizabeth, second daughter of Richard Worsley, Esq., of Mearley or Merley, and also of Twiston, by Isabel, daughter of Henry Townley, Esq., of Barnside. The son and heir of Lawrence Shuttleworth was

Nicholas of Gawthorpe, who married Ellen (or Helen as some of the pedigrees give it) daughter of Christopher Henry Parker, Esq., of Radholme Park and Bolland. (Bowland). The second panel at Gawthorpe gives the initial of this couple as H. & E.S. in 1473. The children of Nicholas Shuttleworth of Gawthorpe and Ellen his wife, were three sons and one daughter, viz .

1. Hugh. 2. Bernard. 3. Richard. 4. Elizabeth.

The 2nd son Bernard, married on the 13th September 1574, at Padiham Church, Jenitta Whitaker (fig 52). Bernard appears to have survived his elder brother; for Hugh, who died in December 1596, left him a legacy of £3 which was paid at twice, and at the payment of the second installment in 1597, Bernard Shuttleworth is stated to be living with John Ree, of the Crosse-banke. In 1602 Copthurst is described as” late Mr. Bernard Shuttleworths”. The third son, Richard, Succeeded to Hacking and it was Anne, his only daughter and heiress, who carried that estate, with her marriage, to Sir Thomas Walmesley the Judge. It is to this Richard that reference is made in the Shuttleworth Accounts where the writer, probably Thomas, third son of 11ugh, who was the elder brother of Richard -calls him “my uncle Richard” so that he was living in November 1582. The eldest son and heir of Nicholas Shuttleworth,

Hugh of Gawthorpe married Anne, daughter of Thomas Grimshaw of Clayton who died (says Whitaker) in 1539. Their panel has H. & A. S. 1577: They were married at Whalley on the 26th October 1540. She was a sister of Richard Grimshaw, who died in 1575, aged 66, and she was buried at Padiham, January 23rd 1597. Hugh Shuttleworth was born in 1504, and he died in December, 1596, aged 92. He was buried at Padiham on the 26th December 1596. In the spandrels of two arched entrances to the dining room at Gawthorpe are four small shields, all bearing the date of 1605 (fig 46), and commemorating Hugh Shuttleworth and his three sons. The first of these has the initials H. S. and below a G. for Hugh Shuttleworth, Gentleman. The second R. S. and below a K. for Richard Shuttleworth, Knight, the third L. S. and below a P. for Lawrence Shuttleworth, Presbyter or priest, and the fourth T. S. and below a G. for Thomas Shuttleworth, Gentleman

The children of the Hugh Shuttleworth and Anne his wife, were three sons and a daughter, viz;

1. Sir Richard Shuttleworth, Sergeant- at- law and chief Justice of Chester.

2. Lawrence (B.D.)

3. Thomas.

4. Ellen, or Ellinor, who, married Nowell of Merlay Parva, or Little Mearley. The eldest son and heir of Hugh was

Richard (fig 24) afterwards Sir Richard, Kt. who was a sergeant at law (receiving the coif on the 4th July 1584) and afterwards the Justice of Chester. He married Margaret (fig 25) youngest daughter of Sir Piers or Peter Legh of Lyme Cheshire, and of Hadock and Bradley, Lancashire: she being the widow of Robert Barton, Esq., of Smithills Hall near Bolton-le-Moors. They seem to have been married before 1582 and to have resided at Smithills where Lady Shuttleworth died in April 1592. Sir Richard survived her until about 1599, (their panel being R. S. K. & M. S. 1599): and, dying without issue, he was Succeeded in the family estates by his next brother.

Lawrence B.D.

(fig 26) Rector of Whichford (A parish of Co. Warwick in the diocese of Worcester) who erected the present Hall at Gawthorpe. His panel states L. S. 1545 and beneath P. N. This Lawrence does not appear to have been married, at least he left no issue and he was succeeded to the estates by Richard eldest son of his younger brother, Thomas. This Thomas who for the first 11 years of the period embraced in the Shuttleworth Accounts acted as the steward of his brother Sir Richard and kept the house and farm accounts married about September 1586 Anne, daughter of Richard Lever of Little Lever, Esq. their panel bears the date the year of their marriage T. A. S. 1586. They had six children. 1. Richard, who succeeded his uncle Lawrence.

2. Nicholas who in 1611 was living in Chambers in Gray’s Inn.

3. Ughtred also of Gray’s Inn, Barrister at Law, whose panel has V. S. 1604.

4. Anne the wife of James Anderton of Clayton, Esq.

5. Ellinor or Ellen who was married at Padiham, March 6th 1609/10 to Sir Ralph Assheton, Bart., according to Burke, being his second wife.

6. Elizabeth wife of Sir Matthew Whitfield of Whitfield.

Anne the wife of Thomas Shuttleworth survived her husband for many years dying in May 1637, aged 68. Thomas died before either of his elder brothers in December 1593 and the accounts for his funeral expenses will be found in the accounts (Anne married, secondly, a Mr. Underhill).

Richard (fig 27) born 1587 succeeded his uncle Lawrence in the estates about February 1608 and married Fleetwood (fig 29) daughter and heir of Richard Barton of Barton in Amounderness, by Mary daughter of Robert Hesketh of Rufford. There is no panel at Gawthorpe of this Richard Shuttleworth and Fleetwood his wife, but only one probably placed by his uncle Lawrence when he and his brothers were young, inscribed R. S. N. S, for Richard and Nicholas the two eldest sons of Thomas. This panel flanks the one already noted to their younger brother Ughtred dated 1604 at which time probably both panels were placed shortly after finishing the new Hall. The children of Richard Shuttleworth were:

1. Richard (M.P. for Clitheroe) who married Jane daughter of Mr. John Kirk citizen of London, by who he had three children.

2. Nicholas who married Margaret, daughter of Thomas Standish, Esq. of Busbury (bishop Shuttleworths Pedigree). This Nicholas was said to be of Clitheroe. His son Ralph married Susanna, daughter of Richard Grimshaw, who died 1575. (Whitakers Whalley).

3. Ughtred baptised 12th October 1617 (Padiham Reg.) who married Jane, daughter of Radcliffe Assherton of Cuerdale, Esq.

4. Barton baptised 7th February 1618 (Padiham Reg.) who married Elizabeth, daughter of Col. John Assheton in the service of Chas. 1. (Whitaker’s Whalley). They had a daughter which would appear from the following entry (Burnley Reg.) Fleetwood, daughter of Major Barton Shuttleworth, baptised at Gawthorpe August 20th 1657″.

5. John of Gawthorpe, Gentleman. He married 20th August 1652 Elizabeth Sherbourne (Padiham Reg.) and had four children. Fleetwood, baptised 28th June 1653 (Padiham Reg.) Catherine, John and Richard (Bishop Shuttleworth’s Pedigree).

6. Edward of whom nothing further is known.

7. William baptised 10th November 1622 (Padiham Reg.) and who is stated to have become a Captain in the Parliamentary Army and to have been slain at Lancaster.

8. Thomas.

9. A daughter died an infant and was buried February 1st 1615.

10. Margaret, baptised 28th December 1623. She was married to Nicholas Townley of Royle. (The Townleys of Royle are descended from Nicholas, third son of John Townley, living 1450 and Isobel his wife, daughter of Richard Sherbourne Esq., of Stoneyhurst).

11. Anne, baptised 24th June 1620, married first John son of Radcliffe Assheton of Cuerdale and second Richard Townley of Barnside and Carr, Esq., who was killed by a bull baited at Gisburn about 1655.

Of these children Nicholas, Barton, John, Edward, Anne, Margaret and Elinor were classified as natural sons and daughters in Richard’s will. (In Dugdale’s Visitation of 1664, the year of Fleetwoods death, Richard stated that he had a second wife, Judith Thorpe, by whom he had the nine younger children j

To return to the eldest of the eleven children

Richard (fig 31) he died during his father’s life and was buried at Padiham, 23rd January 1648 (Padiham Register) leaving three children, Richard, Nicholas, and Fleetwood, a daughter who married William Lambton. The second son Nicholas, of the City of Durham, born before 1664 married Elizabeth, daughter and co-heir of Thomas Moore, of Berwick on Tweed, by whom he had three sons, the youngest of whom, Humphrey, married on 1774 Anna only daughter of Phillip Hoghton Esq., by whom he had five children of whom the second son Philip Nicholas became Bishop of Chichester. This branch of the family settled in Co. Durham, and its pedigree has been compiled by the Bishop.

To return to the eldest son: –

Richard (fig 32) of Gawthorpe, Esq., Born 1644. He was also of Forcett in Gilling, Yorkshire, he married 28th July 1664 Margaret, daughter of John Tempest of Durham and was buried at Forcett 5th March 1680, leaving only one son.

Sir Richard (fig 33) The second Knight of that name in the family who was baptised at Forcett 13th October 1666. He was knighted at Windsor Castle 15th June 1684 and he died 27th July 1687 and was buried at Padiham. A flat

slab in Padiham Church near the communion rail marks the last resting place of this Sir Richard Shuttleworth. At the head of the stone in a sunk circle is an Heraldic shield bearing quarterly 1st and 4th the 3 shuttles for Shuttleworth 2nd and 3rd the three boars for Barton. (the stone has now been moved to the side altar.) Below is the simple inscription “Sir Richard Shuttleworth died 27th July 1687”.By his wife Catherine, “the Infantor” only child and heir of Henry Clerke, M.D., President of Magdalen College, Oxford, he left a younger son Clerke Shuttleworth of Nottingham, a daughter Catherine and his son and heir :-

James Kay-Shuttleworth

Janet Shuttleworth, daughter and heiress of Robert Shuttleworth, married James Kay on February 24, 1842. James assumed the name and arms of Shuttleworth by royal license when he married Janet. They had four sons and one daughter. James Kay-Shuttleworth worked very hard throughout his life on efforts to improve the public health and education of the poor in England. His biography appears as shown below in the 1993 “Dictionary of National Biography6.” James and Janet Kay-Shuttleworth apparently had Gawthorpe extensively remodeled during their lives at the hall.

KAY-SHUTTLEWORTH, Sir JAMES PHILLIPS (1804-1877), founder of the English system of popular education, born at Rochdale, Lancashire, on 20 July 1804, was son of Robert Kay, and was brother of Joseph Kay, Q .C. [ q.v.], and of the Right Hon. Sir Edward Kay, lord justice of appeal in the supreme court. As a youth he was engaged in the bank of his relative, Mr. Fenton, at Rochdale, but in his twenty-first year, November 1824, entered the university of Edinburgh as a student of medicine. Before long he became prominent as one of the most earnest, able, and brilliant students in the university, and as an impressive speaker at the meetings of the Royal Medical Society, of which he was elected senior president at the commencement of his second session. While a student he acted as clinical assistant to Dr. Alison and Dr. Graham during an epidemic of typhus, and he resided for a year at the Royal Infirmary as clerk of the medical wards. He also spent an autumn studying anatomy in Dublin. Both there and in Edinburgh he had opportunities of observing the condition of the poor. He was admitted to the degree of M.D. at Edinburgh in August 1827, his thesis being ‘Do Motu Musculorum.’ Shortly afterwards he settled at Manchester as a physician. Although an unsuccessful candidate for the post of physician at the Manchester Infirmary, he obtained for some years an ample field of medical experience as medical officer of the Ancoats and Ardwick Dispensary mainly instituted through his own and exertions, in a poor and populous district of Manchester. He was also secretary to the board of health at Manchester, and during the terrible first outbreak of cholera in 1832 was most devoted in his attendance on the sufferers at the cholera hospital. He thus became painfully alive to the insanitary surroundings of the poor, and in 1832 published a valuable pamphlet on ‘The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes employed in the Cotton Manufacture in Manchester,’ which drew attention to the evil conditions of life among the operative population, and was followed by the local adoption of measures tending to sanitary and educational reform. In a paper read before the Manchester Statistical Society in 1834 on The Defects in the Construction of Dispensaries, and by the steps which he took, in conjunction with William Langton [q. v.], to establish the Manchester District Provident Society, he made further endeavours to benefit the poorer classes of society.

In 1831 he had anonymously published ‘A Letter to the People of Lancashire concerning the Future Representation of the Commercial Interest;’ and he threw himself heartily into the reform and anti-corn law movements.

During the early period of his residence at Manchester he resumed experimental researches on asphyxia, which he had begun at Edinburgh, and in 1834 he published his treatise on The Physiology, Pathology, and Treatment of Asphyxia (London, 352 pages), which secured for him some years later the Fothergillian gold medal of the Royal Humane Society. The work remains the standard text-book on the subject. ‘

His philanthropic efforts on behalf of the poor, his experience among them, and his grasp economic science, brought him to the notice of the government as one specially well fitted to locally introduce the new poor law of 1834. He became in 1835 an assistant poor-law commissioner, and spent some years in that capacity, first in the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk, and afterwards in the metropolitan district, including Middlesex and Surrey. His valuable reports on the training of pauper children were published by the government in 1841.

From that time forward his life was devoted to the introduction and development of a national system of education. In 1839 a committee of the privy council was nominated to administer such a grant as the House of Commons might annually vote for public education in Great Britain, and he was appointed the first secretary of the committee or department, retaining for a time the superintendence of the metropolitan schools for pauper children under the poor-law board.

Jointly with his friend Mr. E. Carleton Tufnell, and from their private resources, he established the first training college for teachers at Battersea in 1839-40. Pupil-teachers were transferred from the Norwood pauper school and became the first students in the college. He at first lived in the house and superintended the whole working of the institution. The experiment proved eminently successful, and the plan was afterwards adopted and its working extended by government aid. The existing system of public education rests wholly on Kay’s methods and principles. Trained teachers, public inspection, the pupil-teacher system, the combination of religious with secular instruction and with liberty of conscience, and the union of local and public contributions were all provided for or foreseen by him. Matthew Arnold, speaking of his suggestions and their results, says that when at last the system of that education comes to stand full and fairly formed, Kay-Shuttleworth will have a statue. Owing to a serious though, as it proved, temporary breakdown of health from extreme overwork, he resigned his office of secretary to the committee of council in 1849, and on 22 Dec. that year was created a baronet.

The history of his measures must be sought in the minutes and reports of the committee of council, and in the pamphlets published on the subject between 1839 an 1870. His own pamphlets on education and other a social questions are numerous. The chief of them he collected in the following owing volumes: 1. ‘Public Education as affected by the Minutes of the Committee of Privy Council from 1846 to 1852,’ London, 1853, 8 vo 500 pp. 2. ‘Four Periods of Public Education, as reviewed in 1832, 1839, 1846, and 1862,’ London, 1862, 8vo, 644 pp. 3. ‘Thoughts and Suggestions on certain Social Problems, contained chiefly in Addresses to Meetings of Workmen in Lancashire,’ London, 1873, 346 pp. He also wrote two novels, entitled ‘Scarsdale, or Life on the Lancashire and Yorkshire Border Thirty Years Ago,’ 1860, 3 vols., and ‘Ribblesdale, or Lancashire Sixty Years Ago,’ 1874, 3 vols. To the Fortnightly Review for May 1876 he contributed a paper on the Results of the Education Act.’

During the terrible distress caused by the cotton famine in Lancashire (1861-5) Kay-Shuttleworth threw himself with fervour into the administrative work of relieving the sufferings of the operatives while guarding against the risk of pauperising them, and he acted as vice-chairman, under Lord Derby, of the great organisation at Manchester known as the central relief committee. In 1863 he was high sheriff of Lancashire, and in 1870 received the honorary degree of D.C.L. from the university of Oxford. He took an active part in the organisation of the liberal party in Lancashire for many years, and in 1874 contested North-east Lancashire unsuccessfully, with Lord Edward Cavendish as his colleague. He served on the royal commission on scientific instruction and the advancement of science, presided over by the Duke of Devonshire, from 1870 to 1873. He was also occupied in his later years with the reform of the administration of some local grammar schools, especially those of Giggleswick and Burnley. He died at his London residence, 68 Cromwell Road, on 26 May 1877.

He married, on 24 Feb. 1842, Janet, daughter and heiress of Robert Shuttleworth of Gawthorpe Hall, near Burnley, Lancashire, whose name and arms he assumed by royal license on his marriage. Lady Kay-Shuttleworth died on 14 Sept. 1872, leaving four sons and one daughter. The eldest son, Sir Ughtred James Kay-Shuttleworth, M.P., was created Baron Shuttleworth in 1902.

[Information from Sir Ughtred Kay-Shuttleworth, including a manuscript memoir by Dr. W. C. Henry, and notes by Lord Lingen, Lord Justice Kay, and Mr. Ericlisen, besides manuscript notes by Sir J. P. Kay-Shuttleworth; Matthew Arnold’s article on Schools in The Reign of Queen Victoria, ed. by T. Humphrey Ward, 1887, vol. ii. ; Manchester Guardian, 28 May 1877 ; Dr. Watts’s Facts of the Cotton Famine, 1886 ; Foster’s Lancashire Pedigrees: Graphic, 9 June 1877 (portrait); another and better portrait is given in McLachlan’s photographic picture of the Cotton Relief Committee.]

C W S

Shuttleworth and Gawthorpe Hall History by Tori Martinez

Tori Martinez has written a very informative summary of Gawthorpe Hall and the Shuttleworth family, which can be found at the following address:

Tori’s article is largely derived from previous works by Conroy and Harland (with full credit to sources) and is presented below:

Gawthorpe Hall — Legacy of the Shuttleworths

by Tori V. Martínez

Starting in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and ending in that of Queen Elizabeth II, Gawthorpe Hall embosomed the lives of one family — the Shuttleworths — for nearly 400 years. Today, this marvel of late Elizabethan architecture seems to emote the history and legacy of a family that came from relatively modest origins, built a fortune, overcame civil wars and tragedy, entertained royalty and, finally, left a palpable modern legacy.

Located between Padiham and Burnley near the Pennines in northeast Lancashire, Gawthorpe Hall is not the rambling palace of English aristocracy, but rather the stately home of an upwardly mobile family with deep roots in the local community. The sprawling rolling hills on which Gawthorpe stands was once part of a permanent Anglo-Saxon settlement that eventually became home to the royal Ightenhill Manor and the surrounding Pendle Forest, where the king’s deer grazed. Around the time of King Edward II’s visit to Ightenhill in 1323, a four-story square pele (or peel) tower with walls eight feet thick was erected at the western end of Ightenhill Manor to serve as a lookout for invading Scots.

In 1388, Ughtred de Shuttleworth acquired 25.5 acres of land on the banks of the River Calder, including the land surrounding the tower. As a younger son of Henry de Shuttleworth of Shuttleworth Hall in neighboring Hapton,

Ughtred would certainly have been considered a member of the landed gentry and, by growing corn on the Gawthorpe estate, was also a gentleman farmer. But as respectable as the Shuttleworth name was in Ughtred’s time, a series of fortunate marriage alliances by his descendents over the next 200 years helped to make the Shuttleworths one of the pre-eminent families of the area.Within six generations, Ughtred’s descendent, Sir Richard Shuttleworth, was a wealthy and successful London barrister who had been made a Serjeant-at-Law — an English barrister of the highest rank — in 1584 and Chief Justice of Chester in 1589. The wealth and landholdings of the Shuttleworth family had increased so much they were asked to lend money to Queen Elizabeth I in 1588 and 1597. Despite the rise in the family’s fortunes and the addition of further lands at Gawthorpe, the major landmark on the property was still the peel tower. After Sir Richard inherited the Gawthorpe lands on the death of his father in 1596, he began making plans to expand the old tower into a residence, and it’s believed that he hired Robert Smythson, the architect of Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire and Longleat in Wiltshire, to design the new hall. Sir Richard died in November 1599 before he could carry out his plans, but the project was continued by his younger brother, the Reverend Lawrence Shuttleworth, who laid the foundation stone of Gawthorpe Hall on August 26, 1600.

For nearly two years, the exterior of the new hall was built using sandstone quarried in Padiham and incorporating the old tower, which was raised more than two stories and can still be seen rising up from the center of the structure. After the exterior was completed in mid 1602, it took another four years to fit out and furnish the interior. Finally, near the end of 1606, Gawthorpe Hall was complete. Although Sir Richard had not lived to see the culmination of his vision, he was not forgotten within its walls. In 1605, two Yorkshire plasterers, Francis and Thomas Gunby, created an ornate plasterwork frieze in the dining room (repurposed in 1816 as the drawing room) that included plaster figures of Sir Richard and his wife Margaret, which alternate with half-human and animal figures. Amazingly, the frieze is still in excellent condition today, 400 years after it was painstakingly created.

Although the new Hall was technically complete, it’s considered unlikely that Lawrence ever actually lived there, since he died in February 1608. Like his brother before him, Lawrence didn’t have any children, so Gawthorpe passed to his nephew, Colonel Richard Shuttleworth — the first official resident of Gawthorpe Hall and also one of the most celebrated early members of the Shuttleworth family. Richard (b. 1587) lived at Gawthorpe Hall for more than 60 years, along with his wife and their 11 children, who were all born there. During that time, he served as High Sheriff of Lancashire in 1618 and 1638, was elected MP for Preston in 1641, and, most significantly, was made a colonel of the parliamentary army when the English Civil War started in 1642. Richard’s responsibility as colonel was to defend northeast Lancashire from the royalists, which meant that Gawthorpe Hall soon became a meeting place for local parliamentarian leaders and forces. During the war, Richard won a critical victory over the royalists when 400 of his men defeated 4,000

royalist troops at Read Bridge. In the process, he may also have saved Gawthorpe from possible capture and destruction, as the royalist troops had been advancing toward Padiham at the time.Despite fighting against the royalists in the Civil War, Richard continued to thrive after the Restoration and left his substantial estates to his eldest grandson, another Richard (b. 1644), who had been brought up in Yorkshire. When the younger Richard died at the age of 36, his son — yet another Richard — inherited Gawthorpe Hall. This Richard (b. 1666) seemed to have a promising future when he inherited the Hall in 1681. He married a young heiress in 1682 and was knighted by King Charles II at Windsor on June 15, 1684 — the second of his family to be so honored. But tragedy struck in 1687 when his father-in-law died, followed only weeks later by Richard himself, with both deaths occurring at Gawthorpe. For three generations, the Shuttleworth family lived elsewhere until, finally, in early 1816, Robert Shuttleworth (b. 1784) made Gawthorpe Hall his home.

In November of 1816, Robert married the daughter of a Scottish baronet, who bore him a daughter, Janet, in late 1817. Once again, it seemed that prosperity and a happy family would again fill the halls of Gawthorpe Hall. Sadly, tragedy again struck the Shuttleworth family in March 1818 when Robert died following a carriage accident. The infant Janet, now heiress to Gawthorpe, was brought up in the south of England, but returned to Gawthorpe after her marriage to Dr. James Phillips Kay, a renowned educationalist, in 1842. Janet’s new husband added the Shuttleworth name and arms to his own, thus changing the family name to Kay-Shuttleworth, and the couple set to work refurbishing Gawthorpe Hall. In April 1849, James commissioned Sir Charles Barry, the architect of the Houses of Parliament, to carefully restore the

house following the original style. Sir Charles also restored the grounds of Gawthorpe Hall to more consistently conform to the Elizabethan style, and the north parterre is probably very similar today to what it was when he created it in 1851. Just as Sir Charles was renewing Gawthorpe Hall to its former glory, so were the Kay-Shuttleworths breathing new life into it. Already members of high society, the family’s status was elevated on December 22, 1849, when James was created a baronet. In March 1850, James and Janet played host to Charlotte Bront, who had anonymously published “Jane Eyre” only three years before. Charlotte visited Gawthorpe again in January 1855, just two months before her death on March 31, and her association with the Hall makes it a popular stop on the Bronte Way to this day.The story of Gawthorpe Hall seemed to come full circle following the death of Janet in 1872, when her eldest son, Ughtred Kay-Shuttleworth — named for his 14th century ancestor — inherited his mother’s estates. The Victorian-era Ughtred lived at Gawthorpe Hall with his wife and six children and had a thriving political career that saw him serve as Liberal MP for Hastings from 1869 to 1880, and for Clitheroe from 1885 to 1902, when he was elevated to the peerage as Baron Shuttleworth (1st Lord Shuttleworth) for his political services. Between 1908 and 1928, he was Lord Lieutenant of Lancashire and it was in this capacity that he entertained King George V and Queen Mary at Gawthorpe Hall in 1913.

For all Ughtred’s seeming good fortune up to time of the royal visit, the following years saw great tragedy for the Shuttleworth family. In 1917, both of Ughtred’s sons were killed in action during the First World War, with each leaving behind a young family. Following these two tragedies, Ughtred retired to his estate in Barbon, where he died — blind and bedridden — at the age of 95 in 1939. Barely a year after becoming the 2nd Lord Shuttleworth, Ughtred’s eldest grandson Richard was killed in the Second World War. He was succeeded by his younger brother, but he too died in the war in 1942. The title then passed to a cousin, Charles Kay-Shuttleworth, who became the 4th Lord Shuttleworth and came to live at Gawthorpe Hall following the end of the war.

Lord Charles had been badly injured in the war, suffering the loss of one leg and the paralyzation of another, and, after marrying in 1947, it was decided that the house was not a practical environment considering his disabilities. The family moved to Leck Hall near Kirkby Lonsdale in Cumbria and left Gawthorpe Hall in the care of Lord Charles’ aunt, the Honorable Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth. The daughter of Ughtred, Rachel was born in 1886 and had lived most of her life at Gawthorpe. She was also the last member of the family to live at the Hall and it seems appropriate that she also died there in 1967. Just five years later, Lord Charles passed ownership of Gawthorpe and the surrounding lands to the National Trust and Leck Hall officially became the Shuttleworth family seat.

Today, Gawthorpe Hall is not only a jewel of Elizabethan exterior architecture and Jacobean interior design, but also a living monument to the Shuttleworth family. Much of the Hall’s original Jacobean and Victorian furniture is currently on display and does much to give it the sense of a historic home truly captured in time. The Hall is also the home of the finest collection of textiles outside the Victoria & Albert Museum in London — the legacy of Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth. The addition of a number of 17th century paintings from the National Portrait Gallery on display throughout the Hall beautifully round out the interior attractions, while outside, the extensive grounds offer plenty of room for exploration, starting with the old gate house at the entrance.

Gawthorpe Hall is open March 25 to March 31 from 1 and 5 pm all week, and from April 2 to November 2 from 1 to 5 pm, except on Mondays and Fridays. The gardens are open all year round from 10 am to 6 pm.

More Information:

Gawthorpe Hall

Further reading:

The Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe, by Michael P. Conroy (1999)

Backcloth to Gawthorpe, by Michael P. Conroy (1996)

Charlotte Bronte at Gawthorpe Hall

As a side note to Shuttleworth and Gawthorpe Hall history, Charlotte Bronte spent time at Gawthorpe Hall in 1850. Barker and Birdsall2 (p. 83-84) describe her visit as follows:

In March 1850 Charlotte went to stay with Sir James and Lady Kay-Shuttleworth at Gawthorpe Hall. The magnificent hall lies near Padiham in Lancashire, just off the present A671. The visit was a surrender to a sort of war of attrition waged by Sir James in an effort to get to know Currer Bell. He was a remarkable man, a great social reformer; in his younger days, as a doctor in Manchester, he had battled against problems of hygiene among the poor and was instrumental in opening schools in workhouses. He lobbied tirelessly for free libraries and free education, and suffered a series of nervous breakdowns throughout his life due to overwork He also had an artistic streak, which drew him to the company of writers. His interest had been aroused by the radical nature of Charlottes novel Shirley.

The publicity-shy Charlotte found Sir James uncomfortably overpowering, but the romantic in her was captivated by the monumental Jacobean hall with its reminiscences of her beloved Walter Scott, gray, antique, castellated and stately. She failed to warm to his wife, whom she found graceless and without dignity. Whether or not she felt that lady Kay-Shuttleworths 200-year-old ancestry and her familys stately home (Sir James had taken her name, Shuttleworth, as the price of the inheritance) should have lent her aristocratic aloofness and condescension is not clear, but Charlotte found her hostesss kind attempts to be friendly painful and trying. Their pressing invitation to stay with them in London over the season she described as a menace hanging over my head. The truth was that, apart from her appalling nervousness in strange company, Charlotte had a deep dread of being patronized. Though never completely at ease, she was to thaw somewhat in her attitude to the Kay-Shuttleworths in later years.

James Kay and his wife, Janet Shuttleworth, are shown in the lower-right corner of the Shuttleworth pedigree in the figure at the bottom of this webpage. Another, equally remote, connection of the Grimshaws to the Brontes occurred at Haworth and is described on the webpage on WilliamGrimshaw of Haworth.

Gawthorpe Hall, Now a British National Trust Property

Gawthorpe Hall was apparently donated to the British National Trust in about 1970, after the death of Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth, the last Shuttleworth descendant to live at the hall. It has become a major tourist attraction of Lancashire. It is described as shown below on the following webpage:

Gawthorpe Hall

Home of the Kay-Shuttleworths, friends of Charlotte Bronte

Gawthorpe Hall, the home of the Kay-Shuttleworths in Padiham, near Burnley in Lancashire was frequently visited by Charlotte Bronte, author of Jane Eyre, and other classics.

Now a National Trust property managed by Lancashire County Council, Gawthorpe Hall, a fine 17th Century house with 19th Century restoration, is set in riverside woods, and includes the following:

- 17th Century National Portrait Gallery paintings

- Jacobean and Victorian furnishings

- The Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth Textile Collections

- Elaborate ceilings and panellings

With a special programme of events planned for 2001, Gawthorpe Hall brings history alive in East Lancashire’s Bronte Country. Please contact Gawthorpe Hall on +44 (0)1282 771004 quoting ref. BHA for a special preview.

History

The Shuttleworth family has been associated with the Padiham area since the 14th Century. As their wealth, influence and social standing increased, Sir Richard Shuttleworth decided to build a hall, calling it “Gawthorpe” (meaning “the place of the cuckoo”). Work was started in 1600, and the building was completed in 1605.

Gawthorpe Hall has associations with the English Civil War, as Colonel Sir Richard Shuttleworth commanded the parliamentary forces in the “Blackburn Hundred”. In April 1642, within only 24 hours, Shuttleworth mustered 400 men and routed Prince Rupert’s 4000 strong army at Read Bridge, thus effectively ending the Royalist cause in Lancashire.

In 1842, Janet Shuttleworth married Sir James Kay of Rochdale, and between 1850 and 1852 the Hall was restored and improved “in a sympathetic Elizabethan style”; at the request of Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth, Sir Charles Barry, famous as architect for the Houses of Parliament in London, was chosen to undertake this work.

In March 1850 Charlotte Bronte visited Sir James and Lady Janet Kay-Shuttleworth at the hall, followed later in the same year by visits to their houses in London and the Lake District. Although Charlotte Bronte’s feelings about her

visits were mixed, by this time she was famous and attracting the attention of the establishment. The Kay-Shuttleworths were instrumental in introducing Charlotte Bronte to society, and also to Elizabeth Gaskell, who subsequently became her friend and biographer.

Gawthorpe Hall is also of particular interest for the Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth textile collections, which are housed here. Of national importance, the collections represent the finest examples of embroidery and lacework to be seen outside the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Murray Shuttleworths Website on the Shuttleworth Family

Murray Shuttleworth of New Zealand maintains a very interesting website on the Shuttleworths. It includes a lot of information on Shuttleworth family history, numerous photos of Gawthorpe Hall from various sources, and several pages of other photos. The introduction shown below is from Murrays website, which can be found at:

http://www.geocities.com/m_shuttleworth_jp/shuttleworth.html

A big Welcome to these web pages.

I am not a professional genealogist, but I have been researching the Shuttleworth family surname for over 20 years as a hobbie and would like to share information and knowledge that I have learnt over the years.

The WWW has opened up a whole lot of new doors for people that is researching and made it a easier task for finding and contacting people with the same interest.

So here we are through these pages and others like it, to link and help researchers of the Shuttleworth family around the world.

Over the next few months I will add new links and genealogy data base on the Shuttleworth family that I have and also that others have and would like to share.

Below you will find links to the history of the Shuttleworth name and what it means (Some of this information has been recorded or written before, and can be found in such books as Burkes Peerage & Baronetage, some information was also supplied by family members), family/relations photos (more will be added over time), other researchers, some Global Shuttleworth pages and some worth while links/sites to have a look at etc.

Any links you find not working please let me know, or if you have a good link that might be helpfull or would like to add your homepage please also let me know and a link can be added.

I would like to thank extended Shuttleworth family members around the World that have contributed info, images for these pages. By sharing our info helps us all for our common goal and makes our research a little easier..

Murray Shuttleworth JP

New Zealand

Winston Churchill, 11th Generation Great-Grandson of Anne Grimshaw and Hugh Shuttleworth

According to Deborah Nouzovsky, in an e-mail of November 10, 2005, Winston Churchill is descended from Ann and Hugh Shuttleworth; her e-mail is shown below. Thanks go to Deborah for making this interesting connection known to the “Grimshaw researcher community”.

Hi,

Anne Grimwhaw and Hugh Shuttleworth are the 11th great grandparents of Winston Churchill.

Hugh and Anne Grimshaw Shuttleworth had son Thomas Shuttleworth who married Anne Lever.

Thomas and Anne Lever Shuttleworth had son Richard Shuttleworth who married Fleetwood Barton.

Richard and Fleetwood Barton Shuttleworth had son Richard Shuttleworth who married Jane Kirke.

Richard and Jane Kirke Shuttleworth had son Richar d who married Margaret Tempest.

Richard and Margaret Tempest Shuttleworth had son Richard who married Catherine Clerke

Richard and Catherine Clerke Shuttleworth had son Richard Shuttleworth who married Emma Tempest.

Richard and Emma Tempest Shuttleworth had daughter Frances Shuttleworth who married John Tempest.

John and Frances Shuttleworth Tempest had daughter Frances Tempest who married Sir Henry Vane. Sir Henry Vane added Tempest to his name upon inheriting Tempest estates.

Sir Henry and Frances Tempest Vane Tempest had son Sir Henry Vane Tempest who married Anne Catherine MacDonnell, Countess of Antrim.

Sir Henry and Anne Catherine MacDonnell Vane Tempest had daughter Frances Anne Emily Vane Tempest who married Charles William Stewart, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry. Added Vane Tempest to the name.

Charles William and Frances Anne Emily Vane Tempest Vane Tempest Stewart had daughter Lady Frances Anne Emily Vane or Vane Tempest Stewart who married Sir John Winston Spencer Churchill, 7th Duke of Marlborough.

Sir John Winston and Lady Frances Anne Emily Vane Tempest Stewart Spencer Churchill who had son Lord Randolph Henry Spencer Churchill who married Jeanette Jerome.

Lord Randolph Henry and Jeannette Jerome Spencer Churchill had son Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill.

So Hugh and Anne Grimshaw Shuttleworth are the 11th great grandparents of Winston Churchill.

Regards,

Deborah (Nouzovsky)

References

1Conroy, Michael P., 1999, The Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe: Lancashire Family History and Heraldry Society, 80 p.

2Whitaker, Thomas Dunham, 1872, An History of the Original Parish of Whalley, and Honor of Clitheroe (Revised and enlarged by John G. Nichols and Ponsonby A. Lyons): London, George Routledge and Sons, 4th Edition; v. I, 362 p.; v. II, 622 p. Earlier editions were published in 1800, 1806, and 1825.

31830 Harland, John, 1856-1858, The House and Farm Accounts of the Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe Hall, in the County of Lancaster at Smithills and Gawthorpe – from September 1582 to October 1621: Manchester, Lancashire, Chetham Society, v. 35, 41, 43, 46.

41820 Selleck, R.J.W., 1993, James Kay-Shuttleworth – Journey of an Outsider: Portland, OR, Woburn Press, 494 p.

5Barker, Paul, and James Birdsall, 1996, The World of the Brontes: London, Pavilion Books Ltd., 144 p.

6Stephen, Sir Leslie and Sir Sidney Lee, 1993, The Dictionary of National Biography, volume X, Howard – Kenneth: Oxford University Press, p1138-1140.

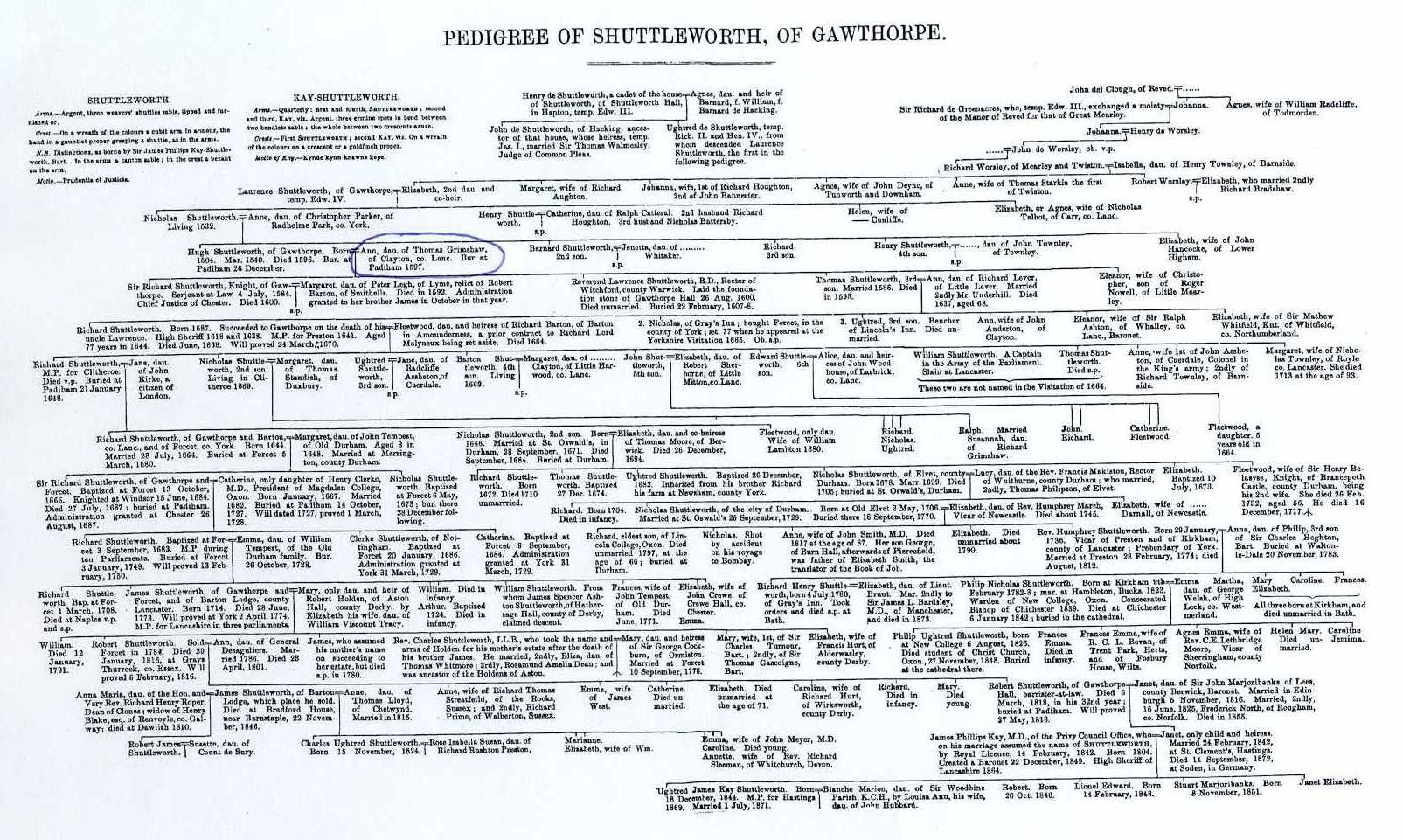

Detailed Shuttleworth Descendant Chart From Whitaker

Whitaker2 (v. II, p. 183-185) presents a very complete descendant chart of the Shuttleworth family with details on many of the individuals. The chart is presented in Figure 13 below. Anne Grimshaw (circled in blue) is shown as the wife of Hugh, 5th generation descendant of Henry Shuttleworth: Ann, dau of Thomas Grimshaw of Clayton, cop. Lanc. Bur. At Padiham 1597.” Whitakers descendant chart begins with Henry (m. Agnes de Hacking.) who is a 5th generation descendant of the earliest known Shuttleworth, “Henry de Shotilworth.”

Figure 13. Whitaker’s Descendant Chart for the Shuttleworth family, with Anne Grimshaw shown in blue circle.

Images from John Harland’s “The House and Farm Accounts of the Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe Hall”

Two images are presented as frontispieces of the first two volumes of Harland’s 4-volume work3, published in the 1850s. The first volume (v. 35) has an engraving of Shuttleworth Hall (Figure 14), and the second volume (v. 41) has a line drawing of Lawrence Shuttleworth (Figure 15 below,) son of Anne (Grimshaw) Shuttleworth and builder of Gawthorpe Hall. Figure 16 is a high-resolution closeup of the Shuttleworth arms from the upper right corner of Figure 15.

Figure 14. Engraving of Gawthorpe Hall from Harland3.

Note the detail provided in the engraving.

Figure 15. Sketch of Lawrence Shuttleworth, including his signature below the drawing. The coat of arms in the upper right corner is shown in greater detail in Figure 16. It appears likely that this sketch was made from the painting presented in Figure 9 above.

Figure 16. High-resolution closeup of the Shuttleworth arms from the sketch in Figure 15.

Webpage History

Webpage posted August 2000, updated September 2000, April 2002, July 2002. Updated November 2005 with addition of sections on Shuttleworth history by Tori Martinez and on Winston Churchill by Deborah Nouzovsky.