James Hargreaves, Inventor of the Spinning Jenny

And Spouse of Elizabeth Grimshaw

James Hargreaves is generally credited* for inventing the spinning jenny, one of the most important devices for advancement of the production of cotton textiles in Lancashire County during the early days of the Industrial Revolution. The spinning jenny also exemplified the kind of inventiveness that made the Industrial Revolution possible. James was born in 1720 at Church Kirk and married Elizabeth Grimshaw, also at Church Kirk, on September 10, 1740. Elizabeth was baptized on November 6, 1720 in Churck Kirk; she was born to Henry and Margaret (Broughton) Grimshaw and was the granddaughter of Thomas Grimshaw.

Contents

Importance of Spinning Jenny to Industrial Revolution

Excerpt from Aspin’s Book, James Hargreaves and the Spinning Jenny

References

*The original idea, subsequently expanded and improved upon by Hargreaves, may have come from Thomas Highs, as discussed on a companion webpage.

Connections of Grimshaw family members to RichardArkwright and Edmund Cartwright, inventors of other textile-production devices in the early days of the Industrial Revolution, are described on a companion webpage.

Importance of Spinning Jenny to Industrial Revolution

The spinning jenny’s importance to the Industrial Revolution has been summarized in the Encyclopedia Britannica Online as follows (underline added by website author):

The principle of the division of labour and the resulting specialization of skills can be found in many human activities, and there are records of its application to manufacturing in ancient Greece. The first unmistakable examples of manufacturing operations carefully designed to reduce production costs by specialized labour and the use of machines appeared in the 18th century in England. They were signaled by five important inventions in the textile industry: (1) John Kay’s flying shuttle in 1733, which permitted the weaving of larger widths of cloth and significantly increased weaving speed; (2) Edmund Cartwright’s power loom in 1785, which increased weaving speed still further; (3) James Hargreaves’ spinning jenny in 1764; (4) Richard Arkwright’s water frame in 1769; and (5) Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule in 1779. The last three inventions improved the speed and quality of thread-spinning operations. A sixth invention, the steam engine, perfected by James Watt, was the key to further rapid development. After making major improvements in steam engine design in 1765, Watt continued his development and refinement of the engine until, in 1785, he successfully used one in a cotton mill. Once human, animal, and water power could be replaced with a reliable, low-cost source of motive energy, the Industrial Revolution was clearly established, and the next 200 years would witness invention and innovation the likes of which could never have been imagined.

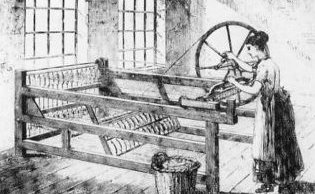

A photo of a modern replicate of the spinning jenny is shown below.

Photo of the spinning jenny from Aspin2, who provides the following caption: “Spinning jenny reconstructed from James Hargreaves’s patent specification of 1770. ‘Jenny’ is an old word for engine.”

Hargreaves’ Background

Hargreaves was born at Ostwaldtwistle, about halfway between the Grimshaw locations in Eccleshill and Clayton-le-Moors, and he made his discovery in about 1764 at Stanhill, about half a mile away. He married Elizabeth Grimshaw on September 10, 1740 at nearby Church Kirk, and they had 11 children from 1744 to 1767:

|

Susan, baptized January 13, 1744/5 |

Betty, baptized March 9, 1755 |

|

Ellen, baptized January 1, 1746/7 |

Jonathan, baptized July 10, 1757 |

|

Henry, died September 1747 |

Harry, baptized March 15, 1761 |

|

Christopher, baptized January 5, 1748 |

Ann, baptized October 28, 1764 |

|

John, baptized November 18, 1750 |

Alice, baptized June 21, 1767 |

|

Mary, baptized October 26, 1752 |

Aspin2 provides the following introductory paragraph on James Hargreaves and his origins; additional detail is given below the photo on this webpage.

James Hargreaves, inventor of the spinning jenny, was born in the semi-moorland district of Oswaldtwistle, near Blackburn, Lancashire, and was baptised at Church Kirk on January 8, 1720/1. His exact birthplace is unknown and apart from the fact that he became a hand-loom weaver, little has been discovered about his early life. His father, George Hargreaves, himself a native of the district, had one other child: Elizabeth, who was three years younger than James. On September 10, 1740, Hargreaves married Elizabeth Grimshaw at Church Kirk. Both are described as “of Oswaldtwistle”, but they appear to have moved away from East Lancashire soon afterwards for their first children were not baptised at any church within a ten-mile radius of the neighbourhood. On January 13, 1744/5, however, “Susan, daughter of James Hargreaves,” was baptised at Church Kirk, and the baptisms of other children show that Hargreaves was living at Brookside, Oswaldtwistle, from 1745/8, and that by 1750 he had settled half a mile away at Stanhill. Hargreaves’s cottage, which is now the village post office, was subsequently occupied by his sister-in-law, whose grandson, John Hindle, died there in 1882, at the age of ninety-eight. An obituary notice says that his house, then known as Rose Cottage, was “where Hargreaves lived and where he invented the spinning jenny.” Hargreaves’s last child, Alice, was born in 1767, while he was living at Ramsclough, on the edge of the moor dividing Oswaldtwistle from Haslingden.

Contrary to popular opinion, the name “jenny” apparently does not come from one of Hargreaves’ children, but rather from an old (or, perhaps, playful) reference to “engine” (see photo caption in Figure 1 above.) None of the children (shown above) is named Jennifer or Jenny.

A possible alternative explanation is that “jenny” wasthe name of a daughter of Thomas Highs, as described on a companion webpage.

Hargreaves’ History on “Cottontimes” website

Source: http://www.cottontimes.co.uk/hargreaveso.htm

IT IS highly unlikely that James Hargreaves had anything to do with the invention of the spinning jenny – despite what the history books say.

The Lancashire weaver got the credit for the ingenious device simply because unscrupulous industrialist Sir Richard Arkwright found it politically expedient to give it to him.

What Hargreaves really did was to improve on a machine that had been designed and built years before by an obscure artisan from Leigh called Thomas Highs, who was the true genius of the Industrial Revolution.

Hargreaves deserves his place in the story of cotton for his perseverance in perfecting the jenny and seeing it into widespread use. But his name should no longer be allowed to overshadow that of Highs.

Born in the Lancashire village of Stanhill, near Oswaldtwistle, in 1720 – he was baptised in the Kirk Church there on January 8th – Hargreaves had no formal education and could neither read nor write. Although no likeness of him is known to exist, he was described as a tall, well-built man with black hair, with an interest in mechanics despite his lack of letters.

His early life was predictably agricultural, which in that region at that time meant combining farming with weaving cloth. He married local girl Elizabeth Grimshaw at the Kirk Church on September 10th, 1740, and they had 13 children with the girls, presumably, helping him by spinning thread for his loom.

However, like many others who had adopted John Kay’s flying shuttle on their looms, he probably felt frustrated by the inability of his family to keep him supplied with thread.

There is nothing to show how Hargreaves came into possession of Highs’s jenny, or more likely, of the plans for it. Highs had built his machine in 1763 or ’64, but did not have the money to patent it. Instead, he built several machines for rental before abandoning his interest in it to concentrate on something he found far more interesting.

THIS is a later version of the Spinning Jenny, with the main wheel switched from the horizontal to the vertical to make operation easier.

What was the jenny? It was a simple wooden contraption that spun several threads at once, instead of the single thread produced by the old-fashioned spinning wheel. It was, in essence, six spinning-wheels bolted together and turned on their side, powered by one large wheel.

A moving carriage bearing the spindles stretched the thread as it pulled away from the body of the machine, imparting twist to the cotton. Then the spindles wound up the thread as the carriage returned, before the process started again.

It was simple enough to be operated by a layman or even a strong child, small enough to fit into a farmhouse kitchen and effective enough to revolutionise the production of thread.

It was a sort of half-way house, something to bridge the gap between the spinning wheel and the heavier, more complicated machinery that came later and required factory conditions in which to operate.

Hargreaves built his first machine in 1766, his principal tool, apparently, being a pocket knife. That first Hargreaves Jenny had eight spindles – an improvement on Highs’s six – and even larger versions followed. Soon, several friends and members of his family were using them.

The thread they produced was coarse and lacked strength, making it suitable only for weft, but it was a step in the right direction.

The jenny’s fame spread quickly, and even manufacturer Robert Peel – grandfather of the future prime minister – invested in some for his nearby Brookside Mill. In fact, there is evidence to indicate that Peel had more to do with the gestation of Hargreaves’s machine than he admitted, and it is possible that he not only helped with its construction, but was also involved with the original idea.

You would have thought that neighbours would have jumped at the chance to buy one of Hargreaves’s jennies, or even to make one of the simple machines for themselves to increase their production and their profits. But that wasn’t what happened.

Hargreaves’s growing success sparked jealousy and fear among his neighbours and, in 1768, an irate mob gathered at Blackburn’s market cross and marched to Stanhill, where they smashed the frames of 20 machines he was building for Peel in a barn. The machine breakers then marched on to Brookside Mill and finally to Hargreaves’s home at Ramsclough. Here, if reports are to be believed, one of the rioters placed a hammer in Hargreaves’s hands and forced him to destroy his own machinery.

This was too much for Hargreaves. He fled to Nottingham, where there was less suspicion of new technology, and opened a small mill in partnership with a man called Thomas James. He continued to develop the jenny, finally taking out a patent in 1770. But he had left it too late. In Lancashire, carpenters were knocking up copies of the jenny by the hundred while other were improving on the original, increasing the number of threads to 80 and beyond.

SIR Richard Arkwright (left) was responsible for crediting Hargreaves with the Spinning Jenny. Sir Robert Peel Snr (right) had more than a little to do with the invention.

All Hargreaves’s effort and determination were of no avail. His machinery destroyed, his patent ignored, he died in obscurity in Nottingham in 1777. Not, however, in poverty – his will amounted to more than £4,000.

By the time of his death, more than 20,000 spinning jennies were in use. But the machine was never more than a stepping stone to the mechanisation of spinning. Within five years, Arkwright had the water frame in mass operation and in the following years Crompton married the best parts of the two machines to produce his hybrid mule, which would quickly take over.

There is another sad postscript to the story. Two of Hargreaves’s daughters ended their lives in penury in Salford, forced to rely on help from Joseph Brotherton, minister of that city’s Bible Christian Church. Brotherton had made enough money from his jenny-equipped Salford textile mill to retire at the age of 36.

Elizabeth Grimshaw’s Origins

Elizabeth Grimshaw was the daughter of Henry Grimshaw of Duckworth Hall in Oswaldtwistle and was baptized November 6, 1720. Duckworth Hall can be seen on the Ordnance Survey map of the area, just northeast of the Grimshaw location in Eccleshill, and southwest of Oswaldtwistle.

Elizabeth’s lineage has been established in the family line of Thomas Grimshaw, which is described on a companionwebpage. Conjectures in the ancestry of Lawrence and Mary (Duckworth) Grimshaw (see companion webpage) indicate a possible tie of this line back to the earliest Grimshaw line of Walter de Grimshaw of Eccleshill, but these conjectures are by no means definitive. Elizabeth Grimshaw’s ancestry is abstracted below and is shown more fully in the webpage of Thomas Grimshaw. Elizabeth and James Hargreaves’ children are also shown.

Thomas Grimshaw (About 1648 – SeeNotes) & Mrs Thomas Grimshaw (About 1652 – )

|—Lawrence Grimshaw (4 Jan 1676 – 8 May 1725) & Jane Ellison (About 1680 – )

|—|—Thomas Grimshaw (1 May 1701 – ) & Sarah Riley (Ryley) (1704 – )

|—|—|—George Grimshaw (1730 – 1812) & Elizabeth Fielden (1730 – )

|—|—|—Lawrence Grimshaw (1728 – )

|—|—|—Ann Grimshaw (1733 – Before 1741)

|—|—|—Dorothy Grimshaw (1737 – 1737)

|—|—|—Thomas Grimshaw (About 1740 – May 1741)

|—|—|—Ann Grimshaw (1741 – )

|—|—|—Mr Grimshaw (1744 – )

|—|—Ellen Grimshaw (1716 – )

|—|—Alice Grimshaw (1714 – 1722)

|—|—Mary Grimshaw (About 1712 – )

|—|—Benjamin Grimshaw (1710 – ) & Jennett Crossley (13 Jul 1712 – )

|—|—|—Lawrence Grimshaw (1734 – )

|—|—Joseph Grimshaw (1710 – )

|—|—Ann Grimshaw (1707 – 1715)

|—|—Levi Grimshaw (1705 – 1746)

|—|—Henry Grimshaw (1704 – )

|—|—John Grimshaw (1702 – )

|—|—Alice Grimshaw (1701 – 1722)

|—|—Lawrence Grimshaw (1719 – )

|—Richard Grimshaw (1674 – SeeNotes)

|—Henry Grimshaw (1679 – ) & Margaret Broughton (1684 – 1731)

|—|—Margaret Grimshaw (1706 – )

|—|—Ann Grimshaw (1710 – )

|—|—Hannah Grimshaw (1710 – )

|—|—Thomas Grimshaw (1714 – 1723)

|—|—Henry Grimshaw (1715 – 1715)

|—|—Alice Grimshaw (1718 – )

|—|—Elizabeth Grimshaw (Bap 6 Nov 1720 – ?) & James Hargreaves (b Stanhill, bap 8 Jan 1720, Church Kirk – 22 Apr 1778). Married 10 Sep 1740.

|—|—|—Susan Hargreaves (bapt 13 Jan 1744/5)

|—|—|—Ellen Hargreaves (bapt 1 Jan 1746/7)

|—|—|—Henry Hargreaves (d sep 1745)

|—|—|—Christopher Hargreaves (bapt 5 Jan 1748)

|—|—|—John Hargreaves (bapt 18 Nov 1750)

|—|—|—Mary Hargreaves (bapt 26 oct 1752)

|—|—|—Betty Hargreaves (bapt 9 Mar 1755)

|—|—|—Jonathan Hargreaves (bapt 10 Jul 1757)

|—|—|—Henry Hargreaves (bapt 15 Mar 1761)

|—|—|—Ann Hargreaves (bapt 28 Oct 1764)

|—|—|—Alice Hargreaves (bapt 21 Jun 1767)

|—Thomas Grimshaw (1682 – )

|—Marie Grimshaw (1684 – )

|—William Grimshaw (1687 – 1720)

FamilySearch Record for Elizabeth Grimshaw’s Family of Origin

Excerpt from “James Hargreaves and the Spinning Jenny” (Chapter 1, “Lancashire”) by Christopher Aspin2

1(First paragraph is excerpted above on this webpage)

Life in the isolated community in which Hargreaves grew up was hard and often harsh. Porridge and oatcake made up the usual diet of the large families who inhabited the small stone cottages, and a few plain pieces of furniture were the only possessions to which most villagers could lay claim. So bad were the roads of Lancashire that a prolonged spell of severe winter weather could easily disrupt food supplies and bring a district to the brink of starvation. Poverty, superstition, insecurity and an ignorance of the outside world combined to produce a dour and forbidding people. “I preached to a large congregation of wild men,” wrote John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, during a visit to nearby Rossendale in 1747 and a year later he encountered in the same neighbourhood “a mob savage as wild beasts, who, undeterred by the authorities, proceed to every extremity of persecution short of murder”. In 1761 Wesley wrote that Padiham was “eminent for all manner of wickedness”. Bull-baiting, cock-fighting, wrestling and kicking matches between naked men wearing iron-tipped clogs were recreations for which the county was notorious.

A few glimpses of life in Oswaldtwistle at the time Hargreaves was living there are afforded by entries in the account books of the village constable. The ’45 Rebellion was the most exciting event recorded and the young weaver was no doubt actively engaged in the anti-invasion measures that were taken. The advance of the Young Pretender’s army – it passed within fifteen miles of the district — caused great alarm and five posts were set up at what to the community was the unusually large cost of L13 11s. 8d. Another 2s. 3d. was afterwards paid to Henry Sherburn “for fire and house when ye watch was kept” and in 1746 sixpence was taken from the funds and put towards “a Bone-fire” on the birthday of the Duke of Cumberland, who had routed the Stuart army at Culloden Moor. One is not surprised to find that the accounts include an item for the repair of the stocks in 1738 and another for taking “two rogues” to the house of correction in 1744.

Farming as a full-time occupation had been largely superseded by the cotton trade which, after nearly two centuries of growth in Lancashire, had become highly organised on capitalist lines. This was particularly true of the district around Blackburn, in which in 1736 two brothers named Livesay employed 2,400 spinners and 600 weavers. Blackburn at that time had a population of about 4,000. It is likely that Hargreaves wove for a manufacturer and that once a week he walked to his master’s warehouse in Blackburn to exchange his finished pieces for a supply of raw material and to be paid according to the quality of his cloth. The woven pieces, known as “Blackburn greys” and “Blackburn checks”, were of cotton weft and imported linen yarn. In 1736, Parliament, which had strongly protected the ancient woollen trade against its younger rival, legalised the printing for home use of this kind of fabric and the demand for the plain greys led to a decline in the making of checks, the yarns of which were dyed before being woven. The greys were sent to London to be printed.

The Lancashire textile workers, though they toiled long hours to earn the necessities of life, at least enjoyed a degree of independence and control over their time and by improving their methods and their simple machinery, the more intelligent among them sought to extend their freedom further. Ironically, their efforts unwittingly hastened the factory system under which much of their liberty disappeared. John Kennedy, the first historian of the cotton trade, says that even before the coming of the great inventions, the multiplication of hand implements was forcing work outside the cottages and that a division of labour among families was emerging.

Hargreaves contributed to this small-scale revolution by introducing one and possibly two improved methods of carding cotton by hand. Carding is the process of disentangling the fibres in the mass of raw cotton and laying them side by side in a filmy roll. At first this was achieved by placing the cotton on a wire brush, known as a hand card, and combing it with another. By Hargreaves’s day a method known as stock carding had been widely adopted. The following description of the operation was written in the 1840s by Henry Ashworth (1794-1880), a prominent Lancashire cotton manufacturer.

The carding was performed by a man having before him a stock of wood or a sort of bench covered with wire cards upon which he laid the cotton. He then sat down and took into his hand what was called a hand card, which he applied to the cotton on the stork card and thus by the backwards and forwards action of the two cards the cotton became combed into a smooth state, fit to be roved and spun.

According to Rees’ Cyclopaedia (1808), stock cards were first used in the woollen industry and were introduced into the Oswaldtwistle area from Rossendale. Hargreaves’s improvement, which doubled the output of the workers,

consisted in applying two or three cards to the same stock and suspending the upper cards, which from their weight and size would otherwise have been unmanageable, from the ceiling of the room by a cord passed over a pulley, to the other end of which was affixed a weight or counterpoise.

Another method of hand carding for which Hargreaves might have been responsible is described by Ashworth in a passage following the one above.

An old man I met with in Edgworth in 1845 told me there was also another form of common carding by hand. A plain surface of wood was standing upright and was covered with wire cards which received the cotton, and the hand card which was applied to comb it was moved up and down against the cotton by means of a treddle on the floor and a wood board acting as a spring was affixed to the ceiling, being tied to the card in hand; and that he could shew me one of those wood springs upon the ceiling of a house at Oswaldtwistle which he had seen used for that purpose when a boy.

This method appears to have been confined to Hargreaves’s neighbourhood, for Ashworth’s account is evidence that it was unknown seven miles away at Edgworth, where stock cards were used until the carding engine was introduced in about 1780.

Seen in retrospect, these early achievements appear important, not so much for their usefulness, as for bringing Hargreaves’s inventive talents to the notice of Robert Peel and so preparing the way for a collaboration between the two men which might well have determined the success of the spinning jenny.

2Robert Peel, cotton manufacturer, pioneer of calico printing and grandfather of Sir Robert Peel, the prime minister, was born at Peel Fold, near Stanhill, in 1732. After his marriage in 1744 to Elizabeth Haworth, daughter of Edmund Haworth, a Lower Darwen chapman, he lived in Blackburn, but returned to the family homestead in 1757. “My father,” wrote his son Robert, “moved in a confined sphere and employed his talents in improving the cotton trade … I lived under his roof until I attained the age of manhood and had many opportunities of discovering that he possessed in an eminent degree a mechanical genius and a good heart.” Peel, who for some years combined farming with cotton manufacturing, sought Hargreaves’s assistance in 1762 in constructing a carding engine “consisting of two or three cylinders” from which the cotton was stripped by two women using hand cards. The machine had only a short life and was laid aside because of Peel’s “other avocations”, among which calico printing and a close interest in the spinning jenny may be numbered. Whether or not Peel knew of the carding engines previously patented by Lewis Paul and John Bourn it is impossible to say: what is certain is that his machine, like theirs, lacked a contrivance for removing the carded cotton, and it was to this problem that Hargreaves returned once he had become established in Nottingham.

The precise date of Peel’s venture into calico printing is uncertain, as are the circumstances surrounding its beginnings. There is evidence that the trade secrets were learned from a Dutchman named Voortman, who settled in London to print cloth for the East India Company. An Excise officer who had to visit Voortman’s premises to stamp the printed pieces observed how carved blocks of wood left an indelible mark if applied to cloth previously treated with the salts of iron. The Excise officer was later sent to Lancashire and stayed at the Black Bull Inn, Blackburn, then tenanted by William Yates, who became one of Peel’s partners. Blocks were bought from Voortman and in about 1766 experiments were made at Peel’s farm, where a woman of the family “imitated with a clothing iron the sheen given by rolling.” According to Sir Lawrence Peel, writing in 1860, Jonathan Haworth, Peel’s brother-in-law and other partner, learned calico printing in London as a young man and it is possible that he went there as a result of the Exciseman’s visit to Blackburn. One of the early patterns was a parsley leaf which became a favourite in the trade and earned its innovator the nickname “Parsley Peel”. Sir Lawrence says that Peel scratched the design on a pewter dinner plate on seeing a sprig of parsley brought in from the garden by his daughter. Peel is said to have hawked his first pieces about the countryside from a cart, but when the partners became established at Brookside, Oswaldtwistle, they sold their cloth from a warehouse in Manchester.

3Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny about the time Peel was carrying out his first experiments with calico printing. Arkwright puts the date of the discovery at 1767, but in view of the great difficulties Hargreaves undoubtedly had in making the machine efficient and the fact that he made several before leaving Lancashire in 1768, one is more inclined to believe the compiler of the Transactions of the Royal Society of Arts, writing in 1783:

From the best information hitherto obtained it appears that about the year 1764, a poor man of the name of Hargreaves, employed in the cotton manufactory, near Blackburn, first made a machine which spun eleven threads.

The earliest account of the invention is contained in a letter published in the September 1807, issue of Aikin’s The Atheiaeum, “a magazine of literary and miscellaneous information”. The writer, who signed himself “T”, describes Hargreaves as “a plain, industrious, but illiterate man with little or no mechanical talent,” and goes on:

His first machine, which is still remembered in the neighbourhood, was made by himself and almost wholly with a pocket knife. It contained eight spindles, and the clasp by which the thread was drawn out was the stalk of a briar split in two. It was a rude but successful attempt, and was soon followed by several others of enlarged dimensions, in the workmanship and contrivance of which he was greatly assisted by his friends. The principle of the machine, however, remained the same and has never been altered to this day.

A lengthier account incorporating the facts given above appeared a year later in Rees’ Cyclopaedia. It includes the following anecdote said to be “still recorded in the neighbourhood” at that time.

A number of young people were one day assembled at play in Hargreaves’s house during the hour generally allotted for dinner, and the wheel at which he or some of his family were spinning, was by accident overturned. The thread still remained in the hand of the spinner, and as the arms and the periphery of the wheel were prevented by the framing from any contact with the floor, the velocity it had acquired still gave motion to the spindle which continued to revolve as before. Hargreaves surveyed this with mingled curiosity and attention.

He expressed his surprise in exclamations which are still remembered and continued again and again to turn round the wheel as it lay on the floor, with an interest which was at that time mistaken for mere indolence. He had before attempted to spin with two or three spindles affixed to the ordinary wheel, holding the several threads between the fingers of his left hand, but the horizontal position of the spindles rendered his attempt ineffectual; it is not therefore improbable that he derived from the circumstances above-mentioned the first idea of that machine which paved the way for subsequent improvement.

There is no reason to doubt this suggestion for the machine patented by Hargreaves in 1770 strikingly resembles an overturned spinning wheel.

At the time Hargreaves invented his jenny the demand for yarn was beginning to outstrip the supply. There were two reasons for this. First, John Kay’s “fly shuttle” of 1733, which was widely introduced in the cotton industry during the 1750s, doubled the weaver’s output and made him dependent on several spinners. Secondly, there was a considerable increase in exports after 1760 and as Baines observed, “The one-thread wheel, though turning from morning till night in thousands of cottages, could not keep pace either with the weaver’s shuttle or with the demand of the merchant”. The consequences were recorded by Richard Guest:

Weavers whose families could not furnish the necessary supply of weft had their spinning done for them by their neighbours and were obliged to pay more for the spinning than the price allowed by their masters; and even with this disadvantage very few could produce weft enough to keep themselves constantly employed. It was no uncommon thing for a weaver to walk three or four miles in a morning and call on five or six spinners before he could collect weft to serve him for the remainder of the day; and when he wished to weave a piece in a shorter time than usual, a new ribbon or gown was necessary to quicken the exertions of the spinner. An important crisis for the Cotton Industry of Lancashire was now arrived. It must either receive an extraordinary impulse or… after enjoying partial prosperity, retrograde.”

4Though the jenny gave the “extraordinary impulse”, Hargreaves was by no means the first person to turn his attention to making a spinning machine. Leonardo da Vinci made sketches for one in 1490 and as early as 1678 a patent was granted for

new spinning engine whereby from six to an hundred spinners may be employed by the strength of one or two persons to spin linnen and worsted thread with such ease and advantage that a child of five or foure yeares of age may do as much as a child of seven or eight … and others as much in two days… as they could in three days.

The patent (No. 203) was taken out jointly by Richard Dereham of London and Richard Haines of Sullington, Sussex, but the machine was invented by Haines, who wished to see the linen industry established in England. The novelty of the machine, which was meant to be time-saving rather than labour-saving, was its application of a single source of power to a number of spindles. A manually-operated wheel turned a crank to which the spindles were attached. The spinners were thus spared the task of providing their own power and were free to use both hands to draw out the threads. Haines proposed that his machine should be introduced to provide work for pauper children and criminals in a chain of work- houses extending throughout the country, but his hopes were never realised.

In 1723, Thomas Thwaites, a London weaver, and Francis Clifton, a merchant of Yarmouth, patented a machine for spinning wool, flax, cotton and silk “by certain multiplying of wheels which were never before made use of in England”. (Patent 459.) It is impossible, however, to determine the principle on which the machine was based.

There is no evidence to suggest that either of these inventions was ever put to work, but during the 1740s the celebrated machine of Lewis Paul and John Wyatt, which introduced the principle of attenuating cotton by rollers, received an extensive trial. Paul, who conceived the idea of roller drafting and Wyatt, who was largely responsible for putting the idea into practice, met in Birmingham in 1732 and spent much time and money on the project before Paul took out a patent in 1738. The machine had serious mechanical failings which were never adequately remedied and its industrial career was limited to experiments at Spitalfields, Birmingham, Northampton and Leominster. Had the partners possessed more technical ability, they would doubtless have changed the course of industrial history, but it was left to Richard Arkwright, thirty years after Paul’s patent, to bring roller drafting to perfection.

Details of a machine for spinning cotton by water power, devised in about 1745 by John Kay, inventor of the fly shuttle, have not survived, nor is anything known of a machine to spin and reel cotton that was built about 1753 by Lawrence Earnshaw of Mottram. According to Aitkin, Earnshaw destroyed his invention “through the generous, but mistaken, apprehension that it might take bread from the mouths of the poor”.

Another machine which vanished into oblivion was patented in 1755 by James Taylor, a clock maker, of Ashton-under-Lyne. It-was meant to be worked “by men, horses, wind or water” (Patent 694) and consisted of a line of spindles which were motivated by a cord connected to a revolving shaft. The reference in this specification to the roving being first drawn out “two foot or more or less” and then twisted as desired is reminiscent of the method adopted by Hargreaves in the jenny. It is unlikely that the machine was ever used and Taylor is said to have been compelled to relinquish it “by the ill treatment he received from the prejudice of the working class against the improvement”.

The Society of Arts also took an interest in spinning and in 1761 offered a prize of L50 “for the best invention of a machine that will spin six threads of wool, cotton, flax or silk at the same time; and require only one person to work and attend it”. A Mr. George Buckley was the sole claimant, but the Committee of Manufacturers, which examined the machine in February 1763, decided that it did not fully answer the purpose intended and the offer was discontinued in the following year.

5The early history of the jenny is obscure, but there can be little doubt that Robert Peel took a close and possibly decisive interest in its construction. It is also clear that there was opposition to the machine, and this is the most likely explanation for the inventor’s departure from Lancashire.

A granddaughter of Hargreaves said in 1860 that Peel, observing the large quantities of weft produced by his neighbour, became convinced that “some secret plan of spinning” was the cause. He approached Hargreaves, who allowed him “under promise of secrecy” to see the jenny. Peel, however, immediately said, “If you will not make it public, I give notice that I will.” While one can accept the account of Peel’s curiosity, one can find no grounds for his eagerness to make the machine public, and though Corry says Peel tried to raise a subscription of one hundred. guintas from the manufacturers attending Blackburn cloth market seems more likely that on learning of Hargreaves’s invention, he joined him in perfecting it in secret.

Hargreaves, says Rees’ Cyclopaedia, “derived much important assistance” from Peel’s” hints and conversation”, but two of Peel’s descendants go much further. Jonathan Peel, a great-grandson, in a privately published family sketch, states that the vast importance of the discovery

was at once perceived by Robert Peel, who not only supplied Hargreaves with the means of working out his invention in secret – providing him with an abode for the purpose – but also constantly worked with him and made many practical suggestions for its advancement and improvement.

Hargreaves did in fact remove from Stanhill to Ramsclough, a remote part of Oswaldtwistle, in 1766 or 1767, but whether or not this was at Peel’s suggestion it is impossible to say.

Sir Lawrence Peel, recalling – somewhat imperfectly – information passed on to him in early life by his father, describes his grandfather as “the real inventor of one very important improvement in the machinery for cotton spinning, for which, if he had chosen to claim his own, he might have had a patent”. Sir Lawrence is undoubtedly referring to the jenny, but though his statement is exaggerated, it at least confirms the other statements about Peel’s association with the invention.

According to the Cyclopaedia, popular prejudice was soon excited against Hargreaves and

the threats of his neighbours obliged him to conceal his machine for some time after it supplied the woof or weft for his own loom. It was, however, generally known that he had made a spinning machine, and his wife, or some of his family, having imprudently boasted of having spun a pound of cotton during a short absence from a the sick bed of a neighbouring friend, the minds of the ignorant and misguided multitude became alarmed, and they shortly after broke into his house, destroyed his machine and part of his furniture. Hargreaves soon after removed to Nottingham.

Though Hargreaves was certainly not driven out of the district after making only one jenny – the Cyclopaedia, itself says that he made one or two for some of his relations or friends before leaving – this attack could explain his removal to Ramsclough and the subsequent secret development of the machine with Peel’s help.

Jonathan Peel says that Robert Peel “erected buildings for the reception of the new machines” – presumably at Brookside – and that

At a later period, the people fearing to be thrown out of employment by this labour-saving contrivance, rose and destroyed all the machines and all the buildings which contained them. Hargreaves was harboured and concealed in the house of Mr. Haworth, Mrs. Peel’s father, and ultimately conveyed in secret out of the district to which he never returned.

Sir Lawrence Peel’s account is that the cotton spinning machines used by the firm of Haworth, Peel and Yates

gave offence to the hand-loom weavers of the neighbourhood and were not looked upon altogether with a friendly eye by some in a superior station. A skilled mechanic, whom the firm employed in working out their inventions in machinery, was kept for a time concealed in the private house of Mr. Haworth and worked there in secret, as if he were engaged in some mystery of wickedness.

The “skilled mechanic” was almost certainly Hargreaves, but the house was that of Jonathan Haworth and not that of Edmund as stated by Jonathan Peel. Edmund Haworth died in 1759.

Arkwright says Hargreaves’s “engines were burnt and destroyed” and Corry that an ignorant crowd, “encouraged by the opinion of their employers” broke the inventor’s “mad wheels” and obliged him to lie concealed for some days.

A 1oca1 tradition that the Brookside premises were attacked in 1768 is recorded by W. A. Abram in his History of Blackburn and a contributor to the Accrington Observer in 1890 describes a meeting some years earlier with an old man who kept as a heirloom an implement said to have been used to destroy the jennies. It was, said the writer

a cross between a big drumstick and a huge sledge hammer, consisting of an iron ball of ten pounds weight, perforated so as to admit an ash bough four feet long and two inches thick. This portentous-looking tool was manufactured for the purpose of smashing spinning jenny wherever she could be found. It was this identical weapon which reduced Hargreaves’s ingenious labour-saving device to shivers in 1768.

The most likely date for the attack on the jenny is early March 1768. The Manchester Mercury of March 8 reported that on March 4 “a party of General Mostyn’s Dragoons, quartered here, marched … for Blackburn in order to quell some Disturbances that have happened there”. In the 1768 petitions in the Quarter Sessions Records at the Lancashire Record Office is a warrant for the transport of the baggage of a troop of the 1st Regiment of the Dragoon Guards, commanded by Lt. General Mostyn from Manchester to Blackburn, “the baggage cart to be at the Exchange, Manchester, at 5 a.m. on March 4”. Details of the rioting are unknown, but the appeal for troops is sufficient evidence that it was serious, and the fact that no one was arrested suggests that it had some measure of popular support. Discontent in Blackburn continued to smoulder and two men were later charged with being “wicked and dangerous persons” and declaring on April 2 that “10,000 would come and destroy the town of Blackburn, having signed a paper for that purpose.” Both were acquitted at Lancaster Assizes in August.

Support for early March as the date of the attack is the statement by Arkwright that he went to Nottingham in 1768 “having so recently witnessed the ungenerous treatment of poor Hargreaves”. Arkwright voted at the Preston election which ended on April I and left Lancashire immediately afterwards.

The introduction of the jenny in late 1760s occurred when wages were particularly low and food was particularly scarce and dear, and it is easy to see why a labour-saving device should be attacked by the rough country people whose riotous predilections were so notorious. In more stable times Hargreaves’s jenny, which was a domestic machine little larger than an armchair might have been accepted in the way that his improved method of stock carding had been and as, indeed, the smaller jennies were accepted only a few years later.

Both Jonathan Peel and Corry say that Hargreaves left Lancashire in secret; and Corry and the Cyclopaedia say that he went following an approach from Nottingham. There is no evidence from Nottingham to support this and Gravenor Henson, in his History of the Framework Knitters infers that Hargreaves arrived in the city without friends or capital. Nottingham as the centre of the Midlands cotton trade would have obvious attractions for Hargreaves, but how he came to learn of them is a matter for conjecture. It is possible that Arkwright provided the information. He would almost certainly have tried to discover something about the jenny had he known of it, and his statement that he knew of the attack on Hargreaves implies that he did. Arkwright had visited the Midlands and chose Nottingham for his own first venture into cotton spinning. If the story of an invitation from Nottingham is to be believed, then it is not unreasonable to suppose that the “speculator” referred to by Corry was Hargreaves’s first partner Shipley, and that he was prompted to travel to Lancashire after Arkwright had given an account of the inventor’s plight.

References

1“Mass production — The Industrial Revolution and early developments” Encyclopædia Britannica Online. <http://members.eb.com/bol/topic> [Accessed August 12, 2000].

2Aspin, Christopher, 1964, James Hargreaves and the Spinning Jenny: Preston, England, The Guardian Press, 75 p.

Webpage History

Webpage posted August 2000. Upgraded February 2010 with addition of Elizabeth Grimshaw’s ancestry.