Michael Henry and Maria (Norris) Grimshaw

Westward Migrants from Wisconsin to Minnesota and North Dakota

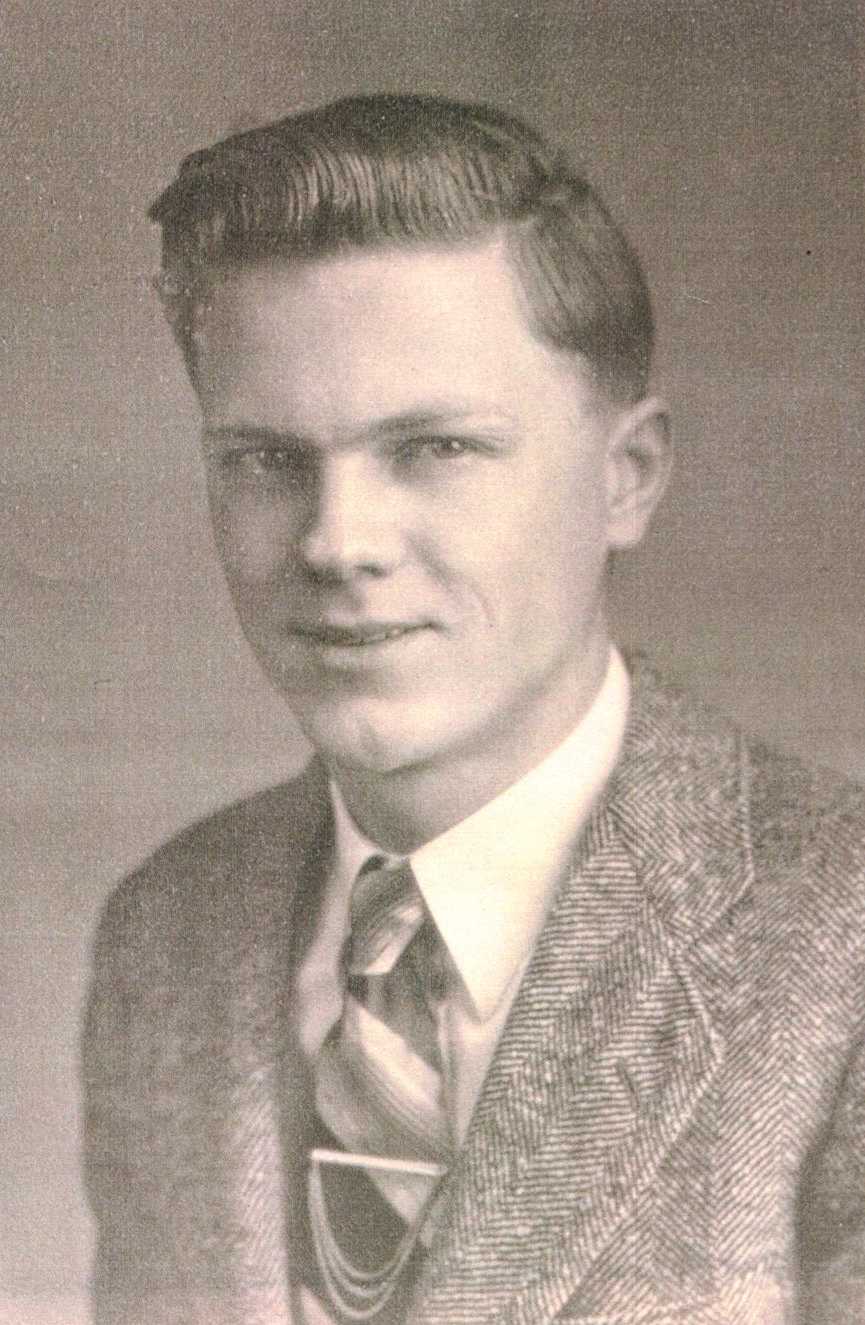

Michael Henry Grimshaw (from Dorothy Zastrow Grimshaw Album)

Michael Henry Grimshaw was born on Wolfe Island (or possibly nearby Kingston), Ontario on October 22, 1856. He emigrated with his parents, John James and Mary Ann (Mahoney) Grimshaw to Richland Center, Wisconsin. On January 14, 1879 he married Maria W. Norris, who was born on March 10, 1861 to Benjamin and Lyda Norris. Maria was the younger sister of Eliza Norris, who married Michaels brother, John Etimer Grimshaw, in 1871.

Michael Henry and Maria had six children, two of whom died in infancy. Maria died at the young age of 32, and Michael remarried to Carrie S.; they apparently had one child. Michael and Maria migrated westward to Minnesota from Wisconsin, where Maria died. Michael moved further to North Dakota, where he is buried.

Contents

Photos of Michael Henry and Maria Grimshaw

Marriage Record for Michael Henry and Maria Grimshaw

Michael Henry and Maria (Norris) Grimshaw Descendant Chart

Michael Henry Grimshaws Ancestors

Bob Grimshaw’s Chronologys of Michael Henrys Family and Descendants

Photos of Michael and Maria Grimshaws Descendants

Michael Henry Grimshaw’s Origins

Personal History of Bob Grimshaw, Michael and Marias Descendant

Website Credits

Many thanks to Bob Grimshaw for providing almost all of the information and as well as the photographs on this webpage.

Photos of Michael Henry and Maria Grimshaw

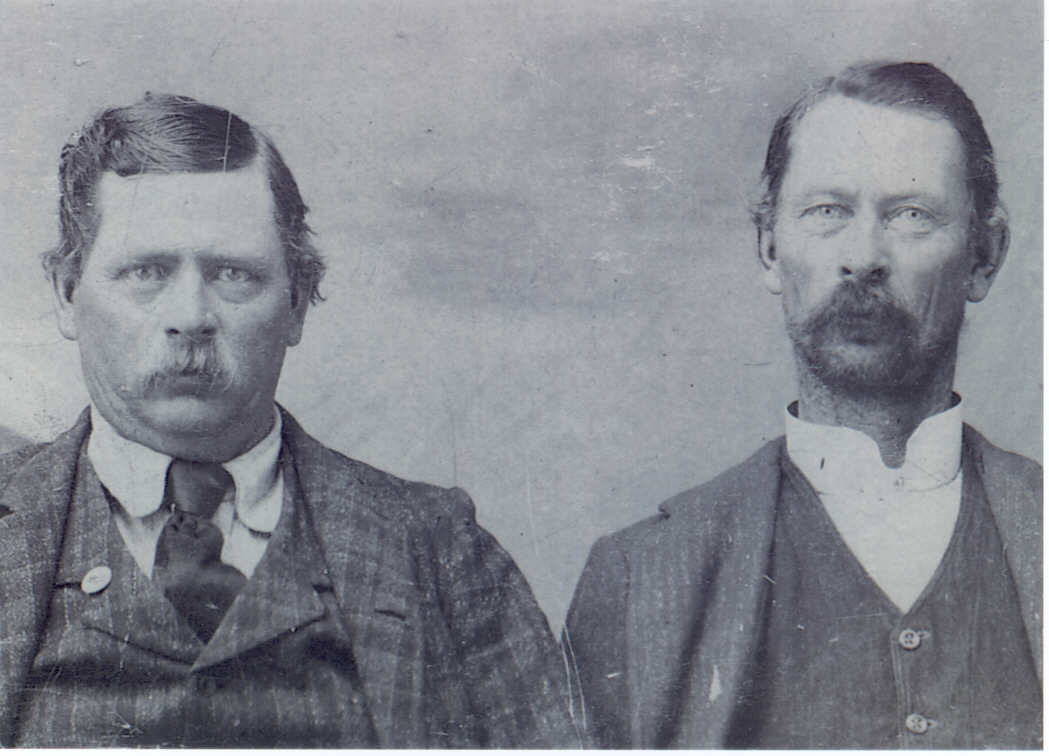

A photo of Michael Henry with his older brother is shown in Figure 1. A photo believed to be Maria and her older sister is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Michael Henry Grimshaw (left) with his older brother, George Thomas Grimshaw. This photo has survived separately through the family lines of both Michael and George. This version is from an album passed down through Georges line.

Figure 2. Photo believed to be of Maria W. (Norris) Grimshaw (left) and her older sister, Eliza (Norris) Grimshaw, wife of John Etimer Grimshaw .

Marriage Record for Michael Henry and Maria (Norris) Grimshaw

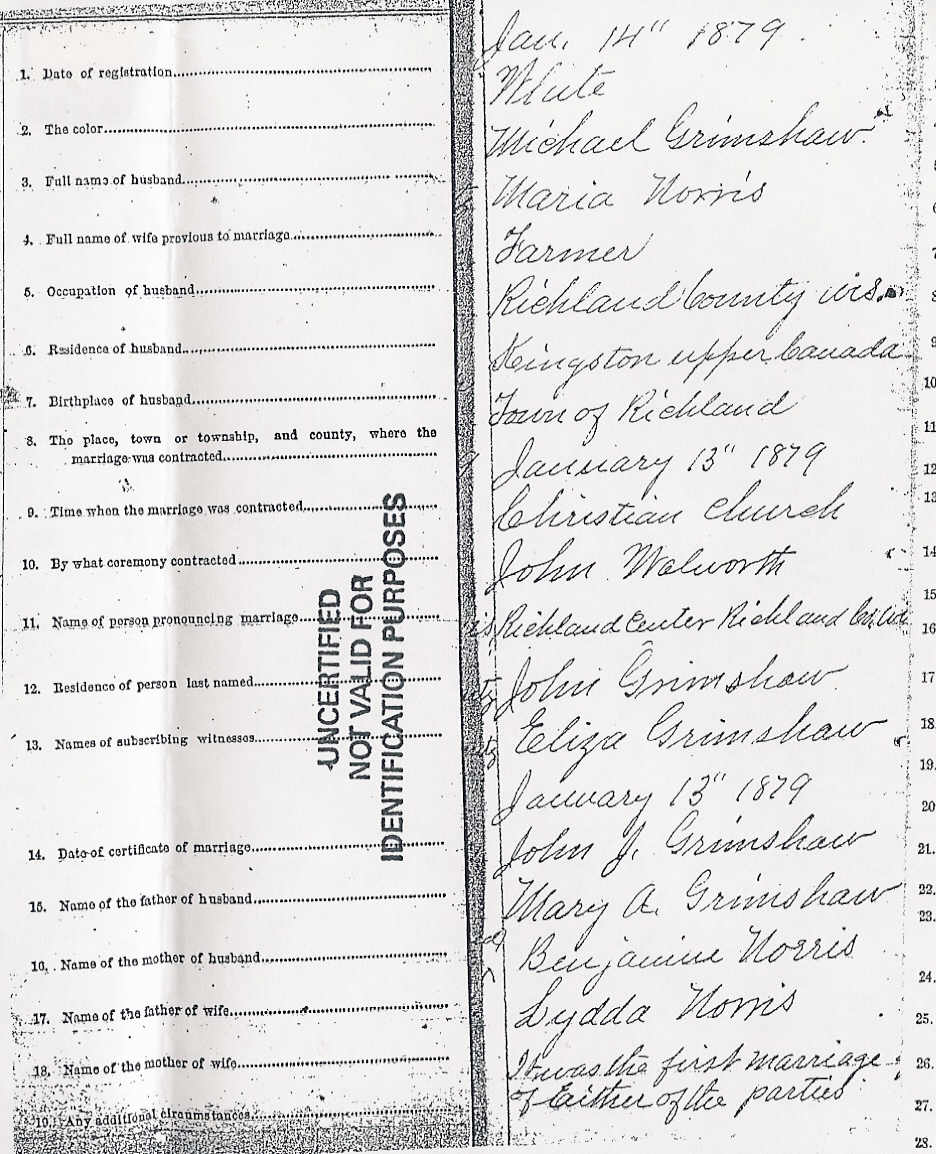

An image of the marriage record for Michael and Maria is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Image of Michael and Maria Grimshaw’s marriage record. Thanks go to Bob Grimshaw for providing this record.

Descendant Chart of Michael Henry and Maria (Norris) Grimshaw

Figure 4 shows descendant chart for Michael Henry and Maria. The descendants of Michael and his second wife, Carrie S., are not known.

Figure 4. Descendant chart for Michael Henry and Maria Grimshaw down through their grandchildren.

Michael Henry Grimshaw (22 Oct 1856 – 26 Oct 1916) & Mariah W. Norris (10 Mar 1861 – 17 Mar 1893)

|—Garth Grimshaw (1880 -)

|—Bertha Luella Grimshaw (16 Jun 1881 – 27 Jan 1921) & Harry Sherman Curry (22 Jan 1872 – )

|—|—Mable Ireria Curry (18 Apr 1898 – )

|—|—Erving W. Curry (22 Feb 1901 – 9 May 1976) & Bertha Garwood

|—|—Grant Norman Curry (19 Oct 1902 – Oct 1950)**

|—|—Hazel Curry (22 Jun 1908 – Dec 1920)

|—|—Minnie Pearl Curry (20 Dec 1909 – ) & Alvin Julino Gehrke (17 Sep 1909 – 31 Mar 1992)

|—|—Rachel Curry (17 Mar 1911 – 31 Jul 1911)

|—William Clarence Grimshaw (8 Jun 1884 – 1 May 1954) & Ragnhild Eckstrom (12 Apr 1888 – 25 May 1975)

|—|—Grace Luella Grimshaw (5 Aug 1915 – 25 Dec 1998) & Robert L Chatham

|—|—Esther Lillian Grimshaw* (18 Nov 1916 – ) & William Fairbrother

|—|—Esther Lillian Grimshaw* (18 Nov 1916 – ) & Barney J. Schwartz ( – 7 Oct 1967)

|—|—Esther Lillian Grimshaw* (18 Nov 1916 – ) & Ralph Norman Grant (8 Dec 1911 – 14 Jul 1981)

|—|—Esther Lillian Grimshaw* (18 Nov 1916 – ) & James David Meredith ( – 18 Jan 1992)

|—|—James Russell Grimshaw (24 Aug 1918 – 11 Apr 1991) & Francis B. Boyko (18 Dec 1927 – 12 Apr 1970)

|—|—Lyla Lucile Grimshaw (22 Apr 1920 – ) & Donald Spencer Murdent (29 Aug 1905 – 19 Jun 1986)

|—|—Fern Ethel Grimshaw (3 Jun 1922 – ) & James A. (Red) Hancock (28 Aug 1914 – 9 Feb 1991)

|—|—Robert William Grimshaw (4 Jul 1926 – ) & Alice Sarah Esau (10 Jun 1929 – )

|—|—Jean Mildred Grimshaw (10 Oct 1928 – ) & James David Brent (10 May 1925 – )

|—|—Nancy Lavone (22 Aug 1934 – ) & Merrill Carl Hebrew (13 Apr 1932 – )

|—Thomas Meridith Grimshaw (8 Aug 1886 – 23 Mar 1887)

|—James Henry Grimshaw (4 Feb 1888 – 9 Dec 1930)

|—Grace Irene Grimshaw (22 Jan 1890 – 1977) & Andrew Bilquist

|—|—George Mervin Bilquist (16 Jan 1916 – 7 Feb 1995)

|—|—Earl Berquist

|—|—Thelma Bilquist

Michael Henry Grimshaws Ancestors

Michael Henry was the son of John James and Mary Ann (Mahoney) Grimshaw and the grandson of George and Charlotte (Menard) Grimshaw; both of these families are the subject of companion webpages. George and Charlotte raised their family on Wolfe Island, Ontario. John and Mary Ann married on Wolfe Island and apparently had all their children, including Michael Henry, while there. They subsequently migrated to Wisconsin in about 1869.

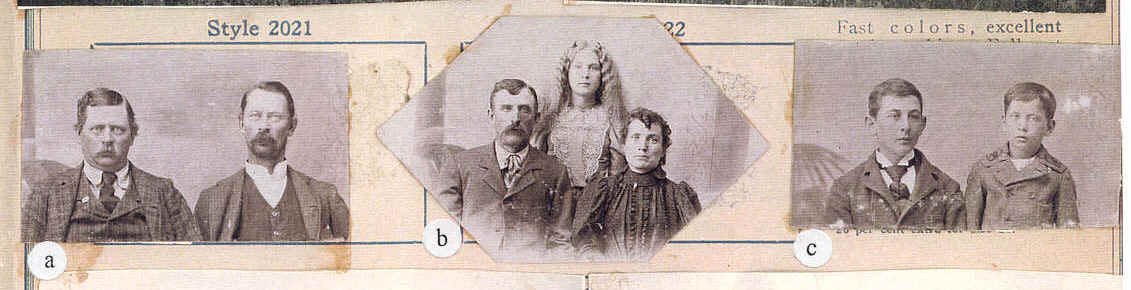

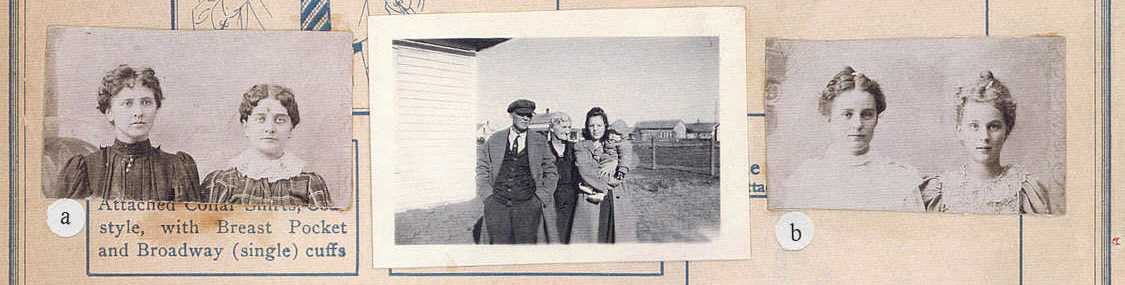

Photos that are believed to be of John James, Mary Ann and their (surviving) children are presented in Figure 5. The album from which these photos came is in the possession of Kernit Grimshaw, a descendant of William Alexanders older brother, George Thomas; it is described in more detail on a companion webpage. The photos in Figures 1 and 2 are also from this album. Figure 6 shows photos from another page of the album, with photos believed to be of the Norris sisters who married Grimshaw brothers.

Figure 5. Photos believed to be of Michael Henry Grimshaw (photo “a,” same as in Figure 1) and his siblings and parents. The two boys in the right photo (“c”) are believed to be of John Etimer and William Alexander, Michaels brothers. It seems apparent that the person who affixed the photos intended to show the entire family, with John James and their daughter, Lida, in the center photo.

Figure 6. Another page from the same album, showing photos clearly of the same “vintage” as those in Figure 5. One of the girls in photo “b” is the same as in Figure 5b (i.e., Lida Grimshaw?) On this basis, the two women in “a” are conjectured to be Maria and Eliza (Norris) Grimshaw, sisters who married brothers. The other girl in “b” could be Lida’s older half-sister, Eliza Mahoney.

Bob Grimshaw’s Chronology of the Michael Henry Branch of the Grimshaw Family

In the fall, 2000, Bob Grimshaw authored the following family history for Michael Henry Grimshaw and his ancestors and descendants. The footnotes are provided immediately after the text. Bob also wrote a personal history of his youth which appears near the bottom of this webpage.

Bobs Introductory Note: I tried to write a chronology of my branch of the family’s migration from Canada. If I’m lucky it will follow. If not I’ll send it.

Grimshaw Migration

FOUR GENERATIONS FROM CANADA TO WYOMING

George Grimshaw was reported to have been born in England and to have emigrated to North America by way of Canada. He came from a family of ship owners and seafaring folk who had been prominent in the County of Lancashire in northwest England. George married Charlotte Menard on September 9, 1817, in St. Luc, Quebec. His father was Guillaume (William) Grimshaw. His mother was Elizabeth Lepninah. William was said to have come to Canada from Germany1.

John James Grimshaw, first son of George and Charlotte, was born in Ontario, Canada (probably on Wolf Island) on August 1, 18292. He married Mary Ann Mahoney in about 18483. She was a widow with a young daughter named Eliza. Her husband and baby had died2 in the crossing from Ireland. John and Mary Ann had five sons and a second daughter. The daughter, Mary Charlotte, and one son, Isiah, died soon after they were born. The surviving sons were George Thomas, 1849; John Etimer, 1850; William Alexander,1854; and Michael Henry, 18564. Michael Henry was my grandfather.

Old family letters5 pass on information that George Grimshaw came to Canada as Captain of one of the family ships. He met Charlotte Menard, a French women in Upper Canada, and married her. When he returned to England with his new bride they were not accepted by the family there and he was given his inheritance and sent away. Their is no evidence to support this, Nonetheless he did return to Upper Canada. The same source reported that John James owned ships on the Great Lakes. If this is true, John could have married Mary Ann and lived almost anywhere in Upper Canada. His son, Michael Henry, told his daughter, Irene, that he was born in Quebec City and went to school there until he was thirteen years old. That time period would check3 with Johns entry into the United States at Cape Vincent, New York, October, 18696.

John James and his family probably moved to Richland County, Wisconsin soon after entering the United States. He was a witness at his sons weddings in Richland Center: William Alexander to Jane Turner on December 26, 1872, and Michael Henry to Maria Norris on January 13, 18797. John James apparently resided in Wisconsin near Richland Center until he died from cancer of the tongue in the small community of Orion, Wisconsin on March 19, 19078.

Michael Henry and Maria Norris had five children: Garth,1880; Bertha Luella, 1881; William Clarence, 1884; Thomas ,Meredith, 1886; James Henry, 1888; and Grace Irene, 1890. Garth and Thomas Meredith died soon after birth. William Clarence was my father. Michael Henry moved to Kansas in about 1888 or 1889. His nephew, Thomas Henry Grimshaw remembered the day that they left from in front of Lida Norriss house in a covered wagon9. They returned to the Magnolia, Minnesota area in 18909. Grace Irene was born in South Dakota, January 22, 1890, on the trip back10. Michaels wife, Maria, died three years later on February 12, 1893, She was ill from injuries suffered from the birth of her sixth child, according to my father, William Clarence. Irene was placed with another family where she stayed until she was an adult. Michael hired a housekeeper to take care of the older children. The housekeeper, Carrie S., became Michaels second wife. The boys had difficulty accepting their new mother and their half sister, May.

Michael Henrys oldest daughter, Bertha, married Harry Curry in 1897, just four years after her mothers death. Bertha was just fifteen years old. My father, William Clarence was just eight years old when his mother died. He continued to live with his father and stepmother until he graduated from the eighth grade. At about fourteen years old, he left home and worked on farms in Minnesota and perhaps North Dakota. filed for a homestead near Crosby, North Dakota, on June 6, 1911. His father filed for homestead near Wildrose North Dakota two years later12. Michael Henry died there on October 6, 191613.

Michael Henrys older brother, George Thomas had filed for land in South Dakota on October 12, 190812. There is some evidence that the sons of John James kept in contact with each other during those years on the homesteads such as album pictures and letters. There is a possibility that Michael Henrys youngest daughter, Grace Irene was born on George Thomass farm, since she wrote that she was born in South Dakota when the family was returning from a trip to Kansas10.

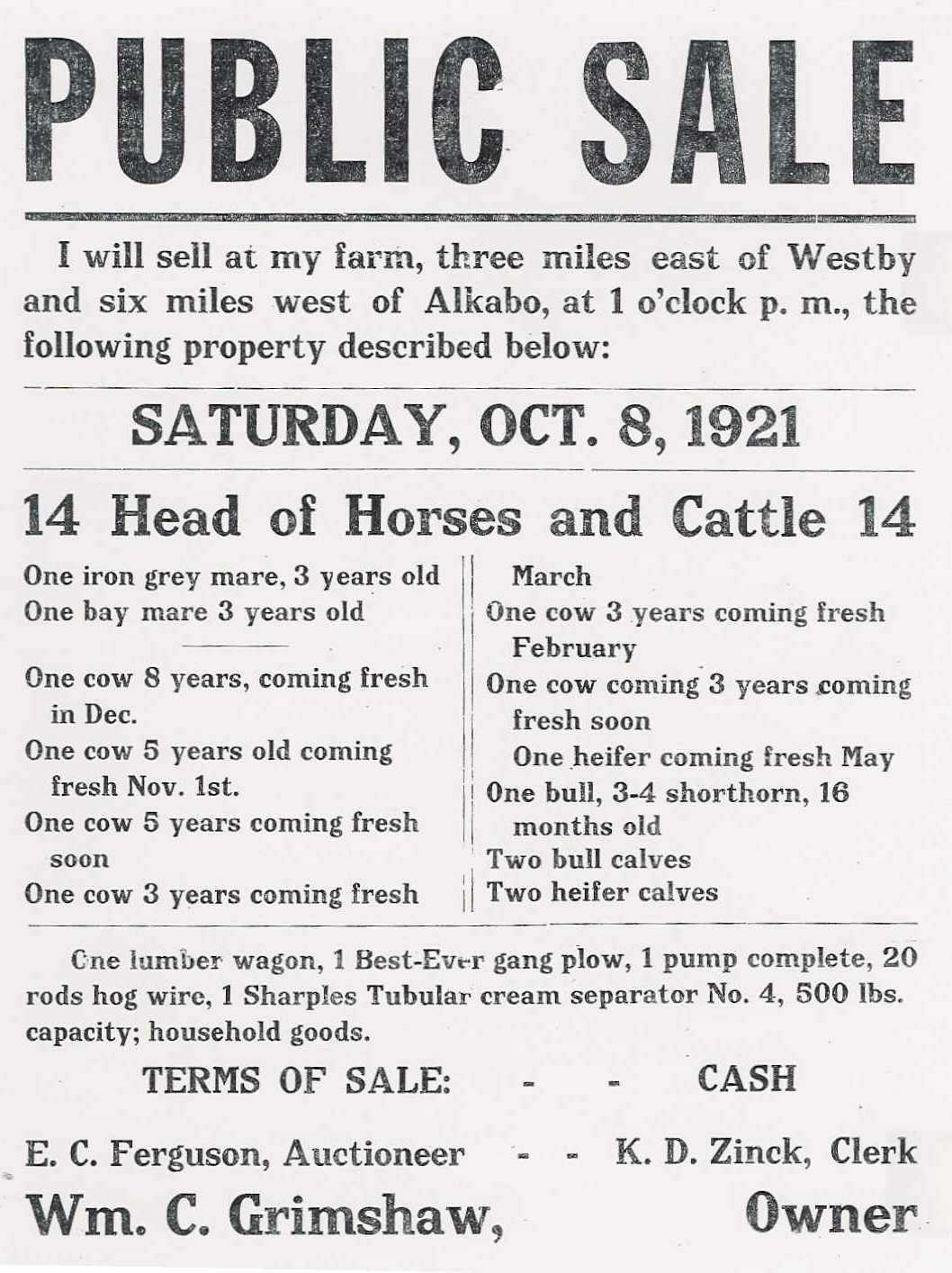

William Clarence met Ragnhild Eckstrom, who had emigrated to North Dakota from Norway, in about 1914. They were married on February 15, 1915. Ragnhild was my mother. Ragnhild filed for land under the homestead act on August 1, 191812. Her land was better than my fathers, so he abandoned his homestead and they moved on to hers. The following years proved to be very difficult. The winters were hard, followed by dry summers6?. The farms in North Dakota were devastated from lack of water. Most of the crops had no irrigation and the outcome of each planting was completely dependent on the weather that followed. By 1921 the William C. Grimshaw family decided to give it up, sell what they could and move on to try again in Wyoming. On October 8, 1921, the Grimshaws held an auction sale where they sold all their livestock and equipment except one team of horses and a wagon14. William and Ragnhild loaded their four children (Grace, Esther Russell and Lyla) into a covered wagon and started the long drive from near the Canadian border to the Northern Wyoming town of Sheridan. Their hired hand accompanied them. When they arrived in Sheridan the hired hand disappeared with the team of horses15. Their beginnings in Wyoming were humble, but they managed to grow in number and become part of the community. Fern was born on June 3, 1922, soon after the family got settled at 705 North Sheridan Avenue. I, Robert, was born on July 4, 1926. Jean was born on October 10, 1928,and Nancy was born on August 22, 1934.

NOTES

1. Madelain Menard, 1999

2. Baptismal Records, Census Records, etc

3. Census Records

4. Family Letters: Thomas Henry to Fern, Irene to Robert, Pearl to Robert; Census Records; Marriage Records.

5. Letter: Thomas Henry to Fern

6. Declaration of intention to become a U. S. citizen, October 22, 1869.

7. State of WI, Registrations of Marriage

8. State of WI, Death Certificate

9. Letter: Thomas Henry to William Clarence

10. Letter; Irene Bilquist to Robert

11. Newspaper article and letters from May

12. BLM Records

13. Death Record

14. Sales Poster (see Figure

15. Conversations

The sales poster referred to in Note 14 has survived in Bob Grimshaws records and is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Poster for 1921 sale of William Clarence and Ragnhild (Eckstrom) Grimshaw family farm in North Dakota, near Montana border. Provided courtesy of Bob Grimshaw.

Photos of Michael and Maria Grimshaws Descendants

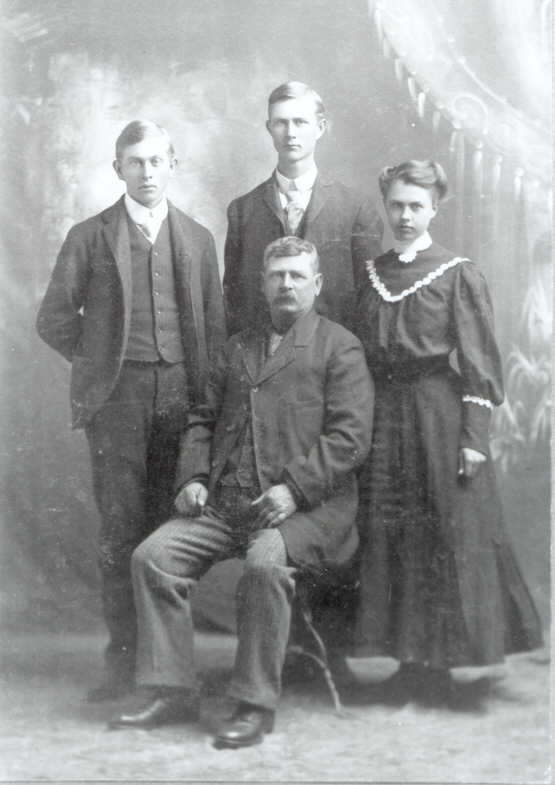

A number of photos of Michael Henry and his descendants have survived and are shown below. A photo of Michael Henry and three of his children is shown in Figure 8. His two oldest children, Bertha and William, are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 8. Michael Henry Grimshaw (Seated) and Children (Left to Right) James Henry, William Clarence, and Irene. (Photo from Bob Grimshaw, April 1999.)

Figure 9. Bertha and William Clarence, two oldest children of Michael Henry and Maria Grimshaw. Tintype photo taken about 1886. Photo provided courtesy of Bob Grimshaw.

William Clarence and his wife, Ragnhild, are shown in a composite photo in Figure 10. Tow of their children, Fern and Robert, are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 10. Composite photo of William Clarence Grimshaw and his wife, Ragnhild (Eckstrom) Grimshaw. Dates of photos unknown. Photo provided courtesy of Bob Grimshaw.

Figure 11. Fern Ethel and Robert William Grimshaw, two of William Clarence and Ragnhild Grimshaw’s children.

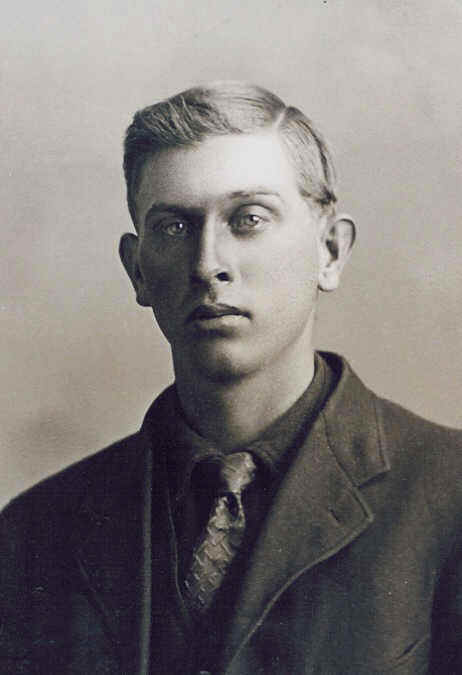

Figure 12 shows two photos of James Henry Grimshaw, who died of an apparent unknown illness at the age of 42.

Figure 12. James Henry Grimshaw. First photo taken during World War I. Date of second photo unknown. Photos provided courtesy of Bob Grimshaw.

Michael Henry Grimshaw’s Origins

Michael Grimshaw’s origins are well documented and are described on webpages for his parents John James and Mary Ann (Mahoney) Grimshaw (click here), grandparents George and Charlotte (Menard) Grimshaw (click here) and likely great-grandparents William and Elizabeth (Zephaniah) Grimshaw click here.

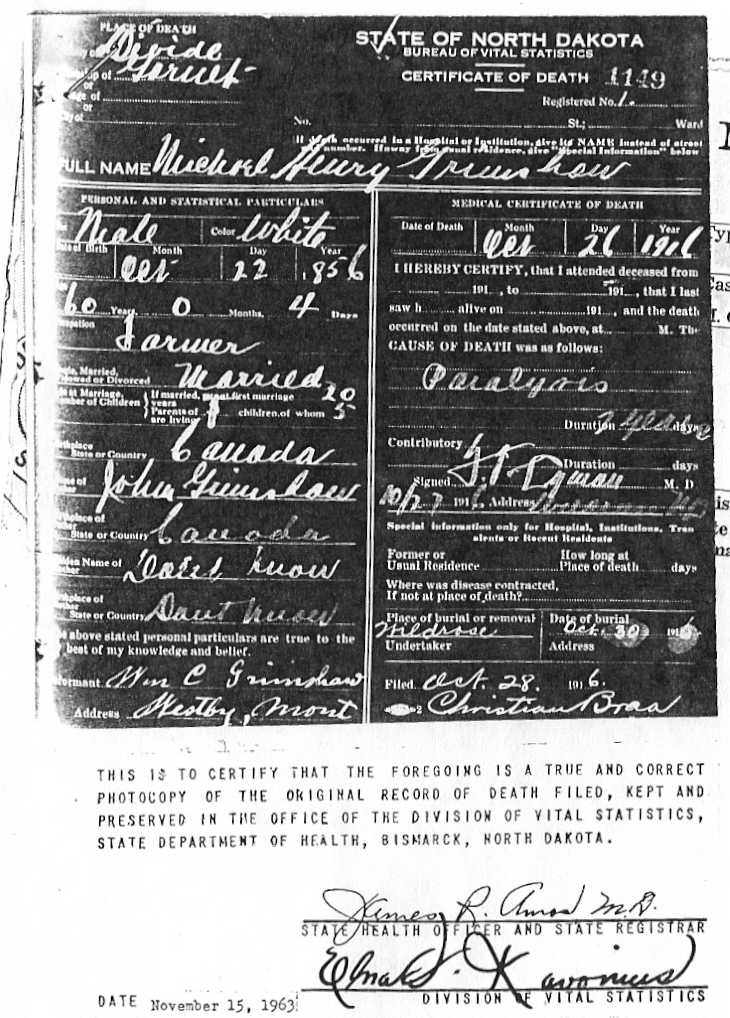

Final Resting Places

As noted above, Maria (Norris) Grimshaw died young and is buried in Minnesota (near Laverne). Her headstone is shown in Figure 13. Michael Henry remarried and lived in North Dakota when he died; he is buried there. His death certificate is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 13. Headstone of Maria (Norris) Grimshaw, which is located in a cemetery near Laverne, Minnesota.

Figure 14. Image of Michael Henry Grimshaw’s death certificate. It indicates that he died of paralysis in Garret or Garnet Township, Divide County, North Dakota on October 26, 1916. He is buried in Wildrose cemetery. The informant was his son, William C. Grimshaw.

Personal History of Bob Grimshaw, Michael and Marias Descendant

In 1998 Robert William (“Bob”) Grimshaw prepared a summary of his early years, including growing up in Wyoming during the Depression, which is presented in the text below. Pictures of Bob are included in Figures 15 and 16.

Figure 15. Bob Grimshaw at High School graduation. “Class of “44.” Photo provided courtesy of Bob.

Figure 16. Bob Grimshaw in 1999, taken with Tom Grimshaw at his home in Modesto, California. Photo provided courtesy of Bob.

Bob’s early life history is provided below.

EARLY EXPERIENCES

(by Bob Grimshaw, Modesto, California, 1998)

I was born on the Fourth of July, 1926, the sixth of eight children of the family of William Clarence Grimshaw and Ragnhild (Eckstrom) Grimshaw. Mrs. Pointer, a friend and midwife was attending my mother. It was not unusual to be born at home at that time. My sisters and brother had gone to Sunday school that morning and were not around when l arrived at 10 o’clock. Mrs. Pointer completed the job and they found me in good health when they returned. She delivered many babies, including my older sister, Fern, and my younger sister Jean after me. I was named Robert William.

My birth took place only four years after our family had emigrated to Wyoming from North Dakota. My father had given up his homestead near Westby Montana in the fall of 1921 after several dry and non-productive years. He held an auction sale on October 8, 1921, when he sold all his livestock and equipment except one team of horses and a wagon. These he drove to Sheridan, Wyoming during the winter of 1921- 1922. The wagon was loaded with his children (Grace, Esther, Russell, and Lyla) his wife (my mother) Ragnhild, all their personal belongings and his hired hand. When they arrived in Sheridan the hired hand disappeared with the team of horses. My father, “Pop”, didn’t pursue him. He said that he owed him back wages, so he would consider his debts paid.

Those early years in Wyoming must have been very difficult for the Grimshaw family. They couldn’t have known many people there. The Boggess family emigrated to Wyoming from North Dakota also. Whether they preceded my parents, I do not know. Fern was born on June 3, 1922 – probably soon after the family arrived in Sheridan. Their first house was a small three room, brown shack at 705 North Sheridan Avenue. They had inside plumbing to the kitchen, but the toilet was an outside privy. We used a wash tub to bathe in. Fem may have been born in that house. I was born there four years later.

My father took whatever work was available. He made use of his building experience from his work on farm buildings in North Dakota. Since he had no transportation at first, he carried his tools on his back. I remember one job that he had when I was a small child, during the great Depression, when he tore down a flourmill in Banner, Wyoming. He carried his tools several miles on his back. Part of his pay was the maple frames and pulleys that the machinery in the mill was made of. We later used the hardwood and line shaft in our wood shop.

Eventually Pop built himself a truck out of parts that he could acquire. I remember telling the kids in the neighborhood that my dad had a Ford truck with a Dodge rear end and a Ruxell axle. I bragged that it could out pull any of the other trucks around there – and it probably could have. Pop never boasted. He was a humble person who seldom used profanity. I remember one time when he did. That was when his coffee cup fell. That’s another story.

Pop habitually used the same coffee mug. Ordinarily the rest of the family didn’t use it. Once I did. That time I dropped it and broke the handle off it. I felt bad and a little frightened because I didn’t know what his reaction would be. To avoid any confrontation, I decided to repair it. In those days the assortment of glues available was not great. We had glue made of hides and hoofs that we used on wood. It was brown and not waterproof. Then we had model airplane glue. It was clear and waterproof – the glue of my choice. I carefully glued the handle back on the mug. It was a fine job. No one could tell that the cup had ever been broken. It was smooth without a telltale line at the joint. Still the cup had to be tested for strength. I filled it with water and bounced it around over the sink. No problem there. The cup went into the cupboard like nothing had happened. Next morning we all sat to eat in the breakfast nook as was our custom. The breakfast nook was just that, a table in a little room with a bench seat on each side, which would hold three or four persons. Mom and Pop sat on the outside and the kids sat in their usual places. Mine was on Pop’s side next to the end. Just Mom and Pop could get out without disturbing another member of the family. I sat apprehensively, waiting to see the successful conclusion of the test under actual use. I wanted Pop to use the cup without discovering that it had ever been broken. Mom poured the hot coffee into his cup and he lifted it up to take a little sip. Then he held the cup in front of his mouth for a second sip as sometimes people do. As I watched the cup suddenly dropped from the handle, which was still held firmly in his grasp. Pop stared at the handle with a look of shock and disbelief on his face. The look turned to surprise and panic as the hot coffee traveled through a pair of bib overalls, pants, and long underwear to reach his bare skin. He uttered an oath as he jumped up and shook the hot coffee from his lap. Apparently the coffee cooled down enough while passing through the layered clothing to prevent any serious damage. The hot coffee had softened the glue and my deception had failed.

We didn’t have a family car. We walked wherever we wanted to go. Sheridan was a small town. It wasn’t more than three or four miles to the other end. In the summer we’d walk all the way out Big Horn Avenue to the gravel pit to go swimming. That must have been about four miles. Family outings were always in Pop’s truck. He’d throw a bale of straw in the back and all the kids would pile in. When we visited Boggess’, he would always put a couple of fifty-gallon drums of water in the back of the truck to help fill their cistern. The barrels were open on the top, so canvas or burlap bags were tied over them to keep down the splashing. Sometimes after driving over the six miles of gravel road to their house the barrels would arrive only half full. We had to be alert to keep from getting soaked during the trip. At the Boggess farm we were always rewarded with a hike in the hills where we saw and hunted all types of small animals including horned toads and snakes. The sandstone bluffs on the Boggess farm were filled with the fossilized remains of fish and plants. Before our trip home, we usually had a big meal of home cooked food. I especially liked Mrs. Boggess’ homemade biscuits and gravy. Mr. Boggess never did any work that I noticed; but his wife, Lizzy, could cut wood, carry water, milk cows and goats, feed the livestock and gather the eggs. She raised a garden in her spare time and cooked delicious meals.

Mr. Boggess must have worked very hard when we weren’t around, because he had a tremendous appetite. He was known to eat more than a dozen eggs at one breakfast. When he visited us he sometimes served himself all the food on the serving tray, leaving none of that particular item for anyone else at the table. His specialty was storytelling. After dinner the younger kids would gather around on the floor around his chair and listen to the stories of the wonders and strange things he’d seen in his travels. He was from Missouri and apparently they showed him nearly everything. He’d tell about possum hunting and how good them dogs were. Some of them could talk – in their own way of course. When they treed that possum they followed him right up the tree a ways. They had hoop snakes, blow snakes, and water moccasins in Missouri. The hoop snakes would grab their tail in their mouth and roll right down the trail after you. The blow snakes puffed up like a balloon and blew at you. I can’t remember now whether they blew some kind of darts or venom; but, whatever they did, it wasn’t good for you. Of course the water moccasin was fast as lightening, and, if it bit you, that was curtains. He told about going goose hunting with Pop. One time he was telling us about a particularly successful goose hunt when he turned to Pop and said, “you remember that hunt Bill. That was the time you shot into a flock of geese and brought down about thirty of them with one shot. The sky was black with those geese. You remember that Bill?” Pop gave a reluctant nod. Sometimes his memory wasn’t as good as Mr. Boggess’. When Mr. Boggess got too old for the rigors of country living he came to town to live. Someone heard him singing ballads one day and asked him to do it over the radio. That he did. After that, when we wanted to hear his stories, we listened to KWYO. Ms singing wasn’t that great, but people liked to hear him.

When I was growing up, the Boggess’ son Frank was an idol to me. He was a real cowboy. He could ride broncs and do all kinds of ranch work. Sometimes he’d drive his Star automobile into town to visit our family. I have no idea what a Star automobile looks like. It was stripped down to just the working parts: the engine, radiator, frame, seat, and wheels. He was very careful to drain the radiator if he stopped more than a few minutes in the winter to prevent freezing. Frank was a very strong man. He was about twice as strong as the average man was. He also had determination. He was shoeing a horse one time and the horse wouldn’t let him cradle his hoof to prepare it for the shoe. The horse finally knocked Frank down. That was it for Frank. He got up and hit the horse right between the eyes with his fist and knocked him down. Frank broke his wrist; but he wouldn’t have had it any other way. The horse had it coming, and if that’s what it took that’s what it took.

Frank thought it was wrong that the Indians could not buy liquor. He decided that he would supply them whenever he could. He made a little money at it too. I dont think he would have done it if he didn’t believe that they were being treated unjustly. Whenever theyd catch Frank selling liquor to the Indians they would throw him in jail. The county jail was in the second story of the courthouse. Id talk to him from the grounds under the window sometimes. Once he threw me some money to buy him some cigarettes. It to took me a while to throw that pack of cigarettes through the bars of that second story window. I was not aware that what I was doing was against the law. I could tell a lot of interesting stories about Frank.

Growing up in Wyoming was a lot of fun. Things were a lot different in 1935 than they are in 1998. When you lifted up the receiver on a telephone you talked to the operator on the central switchboard. She’d say “Number Please.” and you’d tell her the number that you wanted to call. She’d say ” Just a moment please.” and ring the number you asked for. Some families didn’t have a telephone at all. Most of us were on party lines (two or more telephones on the same line) You could tell who the call was for by the nature or the number of rings. Television had been demonstrated in a lab in 1926; but nobody had one and most of us didn’t know they existed. Our family sat in the living room around our Philco radio and listened to music or programs by Jack Benny, Fred Allen, Fiber McGee and Molly, and Major Bowes, or serials like The Shadow and Gangbusters. It wasn’t television, but we looked in that direction just the same. Mrs. Murdent boarded with us some of the time. She loved the radio programs and really got involved in them, especially Major Bowes’ Amateur Hour. Her enthusiasm was contagious. When she listened, we all enjoyed the programs more.

Food was much different in the 1930’s. Potatoes were purchased in 100-pound burlap bags. Flour came in large, 50 pound sacks. Vegetables and fruits came in bushel baskets, wooden boxes or crates. Most food came in bulk, sold by volume or weight. Much of it was canned in season to carry us through the winter. Fresh fruits and vegetables were usually not part of our diet in Wyoming. The only fruits, which could survive in the cold climate, were apples, plums, berries and chokecherries. We always had a vegetable garden from which we would pick fresh vegetables during the season. We’d wash carrots and radishes under the hose bib outside and eat them as in between meal snacks. Mom baked all our breads and rolls. Meat was usually put into casseroles, stews, and other budget stretching dishes. Sometimes we had hamburgers, roasts, chops, and steaks; but they weren’t a large part of our regular diet. Chicken was a regular Sunday dinner treat. We always raised chickens for the eggs and for the meat. Sometimes we had rabbits or squabs which we raised ourselves. Some of the time we had milk delivered or from our cow or goats that we pastured on a field joining our city lot; but most of the time we didn’t have a cow or delivered milk and drank canned milk watered down until it tasted terrible. When times were hardest our meals became very skimpy. Pop was too proud to accept the white labeled cans from the government during the Depression; so we would bring them home from the neighbors and mom wasn’t too proud to serve them. My brother and I brought wild cotton tail rabbits and fish home whenever we could. Wild game was always part of our diet when it was available. We never went out to eat in a restaurant.

When we bought food from a store, it was usually from Sharps Grocery, a small mom and pop store located three blocks from home. Mr. Sharp was a kind-hearted man who extended credit when people ran out of money. Most paid when they could, but some never did. Nevertheless he survived and prospered. The closest thing we had to a supermarket was Sawyer’s Stores. Their motto was “Every day in every way, Sawyers saves you money.” Sawyers had a rail spur that ran behind their store where they unloaded cars of fruit from the West Coast and other food products.

Childrens toys were not as plentiful in the twenties and thirties as the are today. The only early plastics that I remember are celluloid, cellophane and bakelite. Unlike the plastics of today, they were expensive and not ordinarily used for toys. Children’s toys were sometimes home made. We made sling shots, bows and arrows, and rubber guns. Old abandoned inner tubes from car tires were used in the swimming holes and when they couldn’t be kept afloat the rubber was used for slingshots and toy guns. The tires were sometimes hung from tree branches to use as a swing. Store bought toys like tricycles, bicycles, and scooters were handed down. In the winter we used homemade sleds, and toboggans. Good sleds and skis were shared. When we got a good sled with steel runners we kept it repaired and handed it down. New toys were not on the top of our familys priority list when times were hard. Our family had furniture in the house; but some of our friends had to make do with what they could gather together. I stayed for supper at one of my friends house one evening and was surprised to find that they used tin pie pans for plates and tin cans for water glasses. They had a makeshift table. And we sat on empty nail kegs and lard cans. They were a happy family as I remember. None of us were rich, so we didn’t dwell on each other’s poverty or really think of ourselves as being poor.

When I was growing up, most of the farming in Northern Wyoming was done with horses. A few tractors were being used. There were cars in town. Some families had a car. Many families walked. Horses were still used by the iceman and the milkman for door to door delivery. Kids followed the iceman on a hot day to get ice chips to suck on. The iceman would check a cardboard sign in the window to see what size of ice cake to deliver. The iceboxes had special compartments to put the ice in. Below that was the food compartment. Many years after we got a refrigerator we still called it the icebox. In the freezing winter weather, a half of a beef or wild game could be kept hanging from the ceiling of the garage without danger of spoiling.

The milkman delivered the milk in glass bottles with cardboard tops. A little tab would lift up to use as a handle to lift the top off. The milk was delivered before dawn. The streets were lighted by what we called arc lights from the carbon arc lights, which had preceded them. They were actually large incandescent lights mounted in a reflector on the telephone poles. Mom left a note in the milk bottles from the previous delivery when she wanted anything different from the usual delivery. Sometimes in the winter the milk would freeze and expand, exposing a column of cream over the top of the bottle with a round cardboard cap on it. Sometimes we would get mom’s permission to cut it off and eat it like ice cream. Maybe that is where the name “ice cream ” came from – frozen cream.

I was selling papers on the street when I was nine years old. I remember specifically when Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1936. That was a big headline and I sold a lot of papers, especially to the Italians who stopped me to correct the way I pronounced Italians. Selling papers in the winter in Wyoming was a cold job. I made 100% profit on my sales, though. Papers were two for a nickel at the Sheridan Press and sold for a nickel each on the street. When the weather was very cold, I would walk through the businesses to keep warm, especially the bars, pool halls, and bowling alley. Drunks in the bars were an easy touch. Theyd buy my papers sometimes so I’d go home and get out of the cold. Usually I’d just go back and get more papers.

One night when we were waiting for the paper to come out we were playing with the peanut machine in front of the taxidermy shop nearby. We discovered that if we put chewing gum on the penny when we put it in the slot it wouldn’t drop. Then, if we did the same to the penny we put in the empty slot that turned up, the handle went free wheeling and the peanuts poured out the spout. We put a paper bag under the spout and emptied the machine. We didn’t really think of the act as a crime. We thought of it as a prank, kind of like steeling apples from a tree. That was a commonly accepted child’s prank in those days. The taxidermist saw us just as we finished and yelled for a policeman. I took off with the bag of peanuts as fast as I could run and a policeman took off after me as I zipped by. I knew the businesses along Main Street better than the policeman did, so I soon lost him; but, not before we passed through a couple of bars with card rooms in the back. The card players really ducked for cover when they saw the policeman approaching. I got away, apparently without being identified, since no policeman called at our door. The whole experience was so frightening to me that it was hard to sleep nights for a while. I don’t know what happened to the peanuts.

Apparently the police were paid off for the card games; because, everyone in town knew they were there and they continued to operate illegally. I was told about five years after my experience that a tourist from the East, we called them Dudes, walked in a bar on Main Street where their had been a shooting. He ordered a drink and sat down at the bar when he noticed something covered by a sheet over in the comer. He said, “What is that?” The bartender said that there had been a quarrel during a card game and one of the players shot another player. The traveler said, “Does that happen very often around here?” The bartender said, “That’s the first time today.” The traveler left his drink, jumped into his car, which was parked out front, and hi-tailed it out of town.

When I was about ten years old, which would have been in 1936, my mother allowed me to go with my brother Russell and Junior Miller to Yellowstone Park. Russell was eighteen years old and Junior was about the same age. Russell was very resourceful and dependable; however Junior was just the opposite. He had been kicked out of the special grade in about the sixth grade for hitting his teacher. He spent most of his time fooling around with his Model A Ford and generally making a nuisance of himself. He was Russell’s friend, though, and he respected his leadership. How I persuaded them to take me with them, I’ll never know.

The trip to Yellowstone Park was an experience that I’ll never forget. We packed our clothes, camping equipment and tent in Juniors Model A roadster and took off. Before we got to Billings Montana we ran into a cloudburst. Juniors little Model A almost washed off the road. We were about the last car to get through before the road washed out. One larger car came after us. We pitched our tent the first night just outside the town of Livingston Montana along the Yellowstone River. Russell and Junior wanted to go into town and check out the young ladies, but they didn’t want me tagging along, So they looked in the grub box and found a package of fig cookies to bribe me with. They told me that if I’d stay and guard the camp while they were gone, the cookies were all mine. I ate the whole thing. I had the runs half way through the park. When they were looking at Yellowstone Falls, I was looking for a tree to hide behind.

We camped the next night at Old Faithful Geyser in a campground across from Old Faithful Inn. Being used to turning in early, I went to bed in the tent while Russell and Junior stayed out around the campfire. The bears were plentiful all over the park in those days and they were usually given a wide birth while they scavenged around the garbage cans or did pretty much what they wanted. Campers hung their bacon from a high limb out of reach of the marauders. I could hear the garbage cans banging around as I was lying in my bedroll. Suddenly there was a big commotion out around the campground and a woman screamed. Then Russell came into the tent and said that everything was all right now. They had driven the bear away. A woman had tried to feed it from her hand and the bear had bitten her finger off. Russell had warned me to stay away from the bears. After that experience it was no longer necessary. However, I had a personal experience with a bear a little later on while we were fishing for trout in Yellowstone River. I had returned to the car for bait while Russell and Junior continued fishing near by. I sat on the running board of the Model A working with my line when I heard someone approaching from the opposite side of the car. I bent over and looked underneath to see the legs of someone standing on the other side in a pair of black boots. No doubt, they wanted to borrow some bait. I reached up and grabbed the door handle thrusting myself into the car and raised my head up into the face of the cub bear. I asked, “Do you need some bait?” I was shocked, but not completely out of my senses. I ran back to the river as fast as I could go. Russell and Junior were there laughing at me as they watched the frightened bear scale a tall pine tree at the end of the clearing.

We spent several days in the park, then left by the Gardner, Montana, exit and headed back the way we had come. That was a mistake. When we got to Billings Montana the whole town was flooded. We had a flat tire near the railroad freight depot. There wasn’t a dry place to fix it except the railroad loading platform. While Russell and Junior were patching the tire, a railroad “Bull” told us to get off the platform. Junior grabbed his tire iron and told him we weren’t moving until the tire was fixed. The Bull walked away, apparently not willing to use his gun on some desperate kids.

The flood was really bad. Canned goods and personal belongings were floating down the street. We needed to get out of there. We had only enough money to buy gas to get home. All the bridges going south and east were washed out. The only bridge that remained was a railroad bridge that went northeast. By crossing it we could take a circuitous route to get back on the highway to Sheridan, Wyoming. The Model A went thump thump thump across the ties forever it seemed until finally we reached the other end of the bridge and escaped the miserable flood. We were tired and dirty when we arrived home.

Experiences like the Yellowstone Park trip were not an ordinary experience for a ten-year-old kid, even in those days with the loose reins that Mom and Pop held on us. We were expected to perform, but we were also expected to comply with a moral code that seemed to be more of a universal code than a family code. Most of us lived by the same rules and when our mother or father wasn’t there to lay them down for us other adults usually filled in. Most children had chores that they were expected to do and, of course, we had to do our homework. We sent our evenings gathered around our large oak dining room table. Each of the children did homework on a different level. The older children helped the younger ones when the problems were tough. Mom and Pop were often there with us. Mom would sew or embroidery. Pop would read. Sometimes, when our homework was done, we’d entertain ourselves by making free hand drawings. Russell was the best artist. He could draw almost anything. I always admired Russell. Sometimes living with six sisters in the same house was a problem, especially in the morning when we were getting ready for school. We had only one bathroom, and the mirror in it was about 12 inches by 16 inches. Even that was high and not usable until you were tall enough to see into it. I usually settled for a tall skinny mirror that hung on the kitchen wall. The girls were always primping fixing their hair. They’d give each other what they called a permanent wave. The stuff that they used for that smelled awful and penetrated every corner of the house. They used rollers, bobby pins, and even rags to do up their hair so they would look pretty. They sewed and made their own dresses too, and they left partially finished pieces all over the place. Still, it was nice to have them look out for me. It must have been their mother instinct that made them do it. They helped Mom take care of me and watch after me when I was a little kid.

There was only one family of Grimshaws in town. None of the children ever saw their grandmothers or grandfathers. Pop’s parents were both dead before any of his children were born. Grandmother Grimshaw died when she was 31 years old. Mom’s parents were in Norway. We only saw pictures of them. They both lived to a ripe old age; but it was not uncommon for people to die young. Measles, smallpox, chicken pox, diphtheria, whooping cough, and pneumonia were dangerous and contagious. Quarantines were common. Death from these diseases was not uncommon. Sometimes our friends would go home from school sick and never return. One of my friends stepped on a rusty nail, got lockjaw and died. Tetanus shots were not always given for puncture wounds like they are today. My best friend’s mother died of tuberculosis. The only treatment she got that I was aware of was a special diet, which included goat’s milk.

Death of a friend was hard to deal with. Fortunately, as children, we didnt experience the death of a family member.

All our family went to the same schools. The first three grades were at Custer School. From the fourth to the seventh was at Central School. The eighth grade was at Hill School, and the last four grades were at Sheridan High School. The teachers could discipline as necessary. If you got in trouble at school, you usually got double trouble at home. They had “special grades” for problem children. If you couldn’t get along there you were expelled. Schools were good in Wyoming; but they didn’t put up with any monkey business. I had a fifth grade teacher who would twist your ear until she put you down on your knees. Mrs. McDonough, the seventh grade teacher was known to slap unruly students across the face with a wooden ruler. She taught every child in our family, spanning a period of twenty years. In fact she taught nearly every child in Sheridan who passed the seventh grade during her adult lifetime. My oldest sister Grace was the best student in our family. She set an example that none of us could follow. Her grades were always high and she was usually a class officer of some kind. She was an officer in her high school class and on the honor role. The teachers always remembered Grace and expected us to follow in her footsteps; but we didn’t.

Usually teachers demanded a disciplined environment; but sometimes the students got the last laugh, like the time in the fourth grade when the music teacher raised her baton in front of the class and the elastic in her pants snapped and they dropped down. She was a large, heavy woman; but she went tripping out the door like an antelope.

A lot of the time when we were not in school was spent in outdoor activities. I loved to play softball. My glove was a good one that I had earned by selling enough Colliers, Saturday Evening posts and Ladies Home Journals to get the prize. Local business sponsored teams competed at Custer School, a block from (home?). There were no bleachers but small crowds would gather around the sidelines to cheer their team on. Grade school football games were played there also. It was just a dirt field with lime yard markers, which contributed to the injuries players received. Sometimes our uniforms were only a helmet and a pair of shoulder pads. We usually had sweatshirts of the same color so you could tell one team from the other. Only the parochial schools and high schools had complete uniforms to wear. Somehow the Catholics found the money to keep their teams in uniforms, though they were usually patched.

Childhood arguments between the boys were often settled with fistfights. Sometimes we competed for the same area when we sold seeds, magazines, cloverleaf salve, and other merchandise and a little animosity would grow. Edwin Hankee, who lived across than street, was usually after me for some reason. The biggest reason was probably that I was smaller dm he was and he could whip me. His favorite trick was to sneak up on me and slam me in the face as hard as he could before I knew what hit me. He picked on my friend Raymond Reglin a lot too. Raymond had to watch his goats, which provided milk for his family. The doctor had prescribed goats milk for his mother’s tuberculosis. Edwin had a pet lamb, which he picketed out on the school ground with a long rope. He didn’t like his lamb to share the school grounds with Raymond’s goats. Both Raymond and I hated the site of Edwin; but we were afraid of him. One day we decided that we’d had enough; so, we figured out a scheme to get even with him. We each got our pocketknives and headed for the schoolyard. Raymond cut the rope that Edwin’s lamb was picketed on. Edwin screamed threats at Raymond while he caught his lamb and tied it back. Then he ran after Raymond and I cut the rope. After the lamb went Edwin again, then after me. Raymond cut the rope. Then Edwin went after the lamb, then after Raymond. I cut the rope. This routine went on until the rope was getting short and full of knots. Finally Edwin abandoned the lamb and caught Raymond. He sat on him and started beating him. I knew it was time for action; so, I hit Edwin as hard as I could with a flying tackle, which sent us both head over heels. My feet were running when they hit the ground; but I was still two steps behind Raymond. We headed for Raymond’s house with Edwin following close behind. Raymond’s dad was just getting home from his job at the railroad. He was strolling along with his lunch bucket swinging from one hand when he saw us running frantically toward him. Raymond was yelling, “daddy, daddy!” I was yelling, “Mr.Reglin, Mr. Reglin!” Edwin was gaining on us! We began to panic. Raymond yelled, “Daddy! Daddy!” I yelled, “Daddy! Daddy!” Mr. Reglin saw the humor in the situation and began to laugh. Edwin, perplexed and outnumbered, withdrew in search of his lamb. Later, as I returned home, I saw the lamb tied to Edwin’s mother’s clothesline; and, heard Edwin crying as his mother tried to soothe him. Revenge was sweet.

On December 7, 1941, when I was a freshman in high school, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor without warning. That brought the United States into World War II. Most of the able bodied men volunteered for service to our country. Boys under draft age were not allowed to enter the service without the permission of their parents. Some lied about their age and were inducted with the older men. My friend, Elwin Odom, didn’t like school and didn’t like his stepfather; so, he volunteered when he was fifteen years old. He was a big kid and they took him into the U. S. Navy. Many young men who were under age served in all branches of the service. Traditionally men took to the sea at a young age; and, the recruiting officers probably didn’t check the records that closely. I volunteered before I was seventeen and was supposed to be called into service after I graduated from high school. I had passed an examination for officer’s candidate school: but was told that I was one month too old to enter. I took another examination for Army Air Corps Cadet training and passed. I was notified that I would be called when space was available. That was nearly seven months later on January 1, 1945. In the interim, I was able to get a job as a brakeman on the Chicago Burlington and Quincy Railroad. I had worked there previously during the summer months. The railroad’s labor force had been depleted by the draft, so boys of high school age were hired to fill in.

During World War 11 it was easy to see how many sons each family had sent to war. Little banners hung in the front windows of the houses with a star on a white background for each son who had gone to war. If the star was blue, the son was living. If the star was gold, the son had been killed in action. Gold stars were not hard to find in the front windows of Sheridan Wyoming. Some of the boys who lived in our neighborhood were killed, including Raymond Reglin. Fortunately Mom had a blue star for Russell and one for me.

I was inducted at Fort Leavenworth Kansas and went through basic training at Keesler Field, Mississippi. There were about four barracks full of candidates in our group. We all wanted to be airplane pilots; however, the war was winding down and they had plenty of pilots. Consequently they washed us all out for various reasons, except two candidates. We were allowed to choose from several different types of training. I chose to be an airplane and engine mechanic and took a comprehensive course in airplane and engine mechanics at Keesler Field, Biloxi, Mississippi. Then I was transferred to San Diego where I took specialized training at Consolidated Vultee Aircraft factory on the B-32 airplane. Eventually ended up as a flight engineer on a B-17 Flying Fortress. We were in the 53rd Weather Squadron based on the island of Santa Maria, Azores, which was a Portuguese island about three miles long and one mile wide. I had gone to factory school at Consolidated Vultee Aircraft in San Diego, California; and learned to maintain the B-32 airplane, which was operated with hydraulic controls. The B-17 was operated with electric servo motors. Fortunately we had an Engineering Officer who was clever enough to train us in the field. All our flying was over the Atlantic Ocean. We flew through storms while the weather officer took measurements and observations from the nose compartment. When we met a ship at sea, we would fly low over it and identify it. The U. S. and British Navy ships were spic and span; but some of the merchant ships looked dirty and poorly maintained from above. One sometimes could tell where a ship was from by the way it was kept. We passed over schools of whales a couple of times and you could see them spout.

The weather was very mild on the Azores islands, much like California. Soldiers had little to do when not on duty. I hiked all over the island and learned to speak a little Portuguese with the contacts that I made. Some of us constructed a darkroom and made photo developing and enlarging equipment. We spent many hours experimenting with techniques to improve the results from our photo lab. We passed a lot of our time taking photographs of the people and life on the islands.

The Portuguese people we met were quite friendly; however, their culture was about a century behind the times. All were devoted Catholics whose social life was centered around the church. No young Portuguese girl was allowed to associate with the American soldiers. If they did they would be ostracized from the rest of the island’s society. One soldier dated a school teacher and found himself in jeopardy on the road home. Stones were rolled onto his path from the hills above the road.

I was discharged from Fort Sheridan, Illinois, after 21 months of service. The two fellows who were supposed to go into flight training were there. They were being discharged after 21 months of clerical work in an orderly room.

After the war ended, Congress passed the G I Bill, which provided money for the education of all WWII veterans. I wanted to go to college but had no idea what to study. Mom said, “Why don’t you study Architecture? So, I applied to the University of Nebraska and was accepted for the fall semester of 1946. A neighbor, Dick Fisher, was planning to enter at the same time. We decided to room together, and we rented a basement “apartment” next door to his grandmother’s house in Lincoln, Nebraska, and entered school.

About two weeks after school started, the administration office notified me that my grades were too low in high school to qualify for entry into the University of Nebraska. I had graduated in the lower half of my high school class. I pleaded (money spent for moving and starting school etc.) and assured them that my high school grades were the result of the lack of application. They allowed men to stay for the first semester on probation. At the end of the semester, my grades were good, and the probation was lifted.

In 1946 the University of Nebraska had about 10,000 students. Enrolment was greater because so many returning service men had enrolled on the G I Bill. The students were all ages; most of the students were fresh out of high school or veterans. Some of the veterans were invited to join fraternities. Most declined. There were two reasons that I did not accept: first, the cost was too great for me to afford; second, the frat brothers were very immature, they seemed to be much younger than the two or three years that separated us. The veterans actually did better scholastically as a group than the other incoming students. They were serious about getting an education and, of course, they weren’t enamored by the freedom of their first separation from home.

During summer vacation I worked at any kind of a job that was available: water meter reader, construction laborer, surveying rod man and chain man, engineering draftsman, or architectural draftsman. Working as an architectural draftsman caused me to think seriously about what I was training for. I wouldn’t graduate from the university as an architect. Beginning architectural draftsmen were paid seventy-five cents an hour in Wyoming at that time. The architects really thought that you should work for the experience and forgo the salary. I believe that architects like Frank Lloyd Wright actually charged people to work for them. That wasn’t my idea of employment. My car needed gas to run and it took money to buy gas. Most people could not afford to work for so little. Then my employer, C. W. Shaver, A.I.A, drank himself into bankruptcy. I had to hire a lawyer to get my back wages. That took half of what I had coming. I stayed in school until spring: but had seen what we had waiting for us after graduation and didn’t like it. At that time I told my architecture professors that I would leave at the end of the semester. The Dean of the School of Architecture called me in to see if something could be done to keep me in school. My grades were up. He wanted to know what was wrong. I told him that I just wasn’t interested. He persuaded me to take a battery of tests to determine what my interests were. The tests revealed that my interests were similar to those of a teacher, minister, building contractor, and a linotype operator. I left the university with the names of a few schools where building trades were taught.

That was my last year at the University of Nebraska; however, Dick Fisher and I had an experience during Christmas Vacation that year which was (I hope) a once in a lifetime experience. We were caught in the “49” blizzard on the way back to Lincoln, Nebraska, from our home in Sheridan. That was the year that it snowed and blew until most of the Midwest was frozen over. We continued driving toward Lincoln until Dicks Model B Ford could no longer negotiate the highway safely. The cuts were filled in and the drifts were beginning to be impassable. We barely made it into Glendo, Wyoming, where we rented a basement room in the local “hotel” to wait out the storm. The first night the blizzard completely covered the buildings along Main Street. It was the main Street because there was no other street. The hotel patrons dug a tunnel to the bar across the street and kept it open by making frequent trips for anti-freeze. Somehow or other a local sheepherder made it into town the first day and was soon screaming in pain when his frostbitten hands, feet, and nose slowly thawed out.

We heard about the progress of the storm on the radio. I believe that the telephone lines were down. None were available to us. The second night, after spending the evening in the bar across the street we turned in at our basement room. We each had an army cot type bed on opposite sides of the room with a nightstand between us. It wasn’t long before we were both sleeping. We didn’t even turn the light off. We’d had a long evening across the street. Sometime in the middle of the night I decided to go down the hall to the bathroom. When my feet hit the floor they made a splash. I looked down and saw water up around my ankles. Dick’s shoes were floating near his bed like two gunboats. I yelled at him and said, ” your shoes are floating. He yelled back that I’d had too much to drink and to go back to sleep. I persisted until he realized that the heat escaping from the building was melting the drifted snow and water was seeping down the basement walls. We spent the rest of the night resting on the beds with an eye on the water level. The next day the hotel owner managed to get the water pumped out.

After three nights the storm let up a little bit and the people who were stranded in Glendo began to talk about trying to make it out of there. We decided to try going in a caravan. There were about five cars to begin with and Dicks Model B Ford was leading the way. We couldn’t drive through the cuts; so, we took down the farmers fences and drove around the hills with the cuts through them and took down the fences again on the other side of the hill to get back on the highway. The last car fastened the fences back again. As we made progress through western Wyoming and into Nebraska, other cars joined our caravan. We were the first cars to make it through on that road. Sometimes a car would get stuck in a ditch and all the other drivers would gather around the car and practically lift it out. Two construction workers from Oklahoma were driving an old Plymouth coupe with everything they owned packed in the trunk and behind the seat. It seamed that we carried that old car more than it carried itself In spite of the difficulties, our efforts paid off and we made it to clear roads in Nebraska where we went our separate ways.

The blizzard had been one of the worst in the history of the Midwest, certainly the worst that we had ever seen; and, we had grown up in northern Wyoming where the mercury dipped to 40 degrees below 0 at times. Hay was airlifted to cattle in this storm, but many froze to death on their feet, like statues, unable to reach the hay. We saw a freight train drifted over with snow. The steam engine had only the stack sticking through. The fire in the engine was still smoking. Probably it was being maintained while they waited for help, which had been a long time coming.

On my return to Sheridan Wyoming in 1951 I bought my brother-in-laws share in a cabinet shop partnership with my dad. Pop wanted to build houses, which was a good idea. I wanted to build cabinets, which was a bad idea. After six months of just making it, we decided to give it up for the time being, and I returned to school. This time it was LeTourneau Technical Institute in Longview, Texas.

With the exception of an excellent program in chemistry, LeTourneau was on the level of some junior colleges. LeTourneau was an evangelist part time and the rest of the time he was a very successful industrialist. My major at the College was Building Trades Science. The course wasn’t much of a challenge, since Pop had taught me more when I worked with him on construction work than they taught in the shop classes. One of the projects was to build a double hung window and frame. The instructor was surprised when I knew all the dimensions and parts to complete the project. Pop and I had built many windows where all we purchased was the window sash.

LeTourneau also had a school of divinity. Most of the students of religion were of the charismatic type. I thought that some of them acted a little weird. This was especially true of the guy who lived across the hall from me. He thought the world was coming to an end every day. He also played a big base home at the Four Square Gospel Church and practiced in his room. The walls were not insulated and the sound came through into my room. The fact that it sounded like someone moaning in their death throes may have had something to do with his religious beliefs. He also ate in his room and washed his dishes in the drinking fountain.

In spite of the fact that I didn’t like him much, he persuaded me to attend church with him one Sunday. They must have been waiting for me; because, the preacher singled me out right away. He asked me if I was saved. I said “yes”. He said “Are you sure youre saved?” I said “yes”. He said, “If you’re saved, come on down front”. I said that I didn’t want to come down front. Finally, after a lot of hassling, I went down front with a group of people. They were wailing and carrying on. The whole event was embarrassing to me. I decided right there that it would be a cold day in hell before I allowed myself to be caught in a situation like that again. Apparently some people believe that you can’t accept Christ unless you go through an extreme emotional experience.

I left LeTourneau at the end of the semester. The building trades program wasn’t really adequate to prepare a person for a career in building construction. Today, however, they have one of the top rated engineering schools in the nation.

Webpage History

Webpage posted March 2001, Revised May 2001. Reorganized June 2008.