Grimshaw Hall, Knowle

Large Tudor House Located Near Birmingham, England

Photo from real estate ad for the sale of Grimshaw Hall in November 2003 (see below).

Grimshaw Hall is located in the southeast outskirts of Birmingham. It was built in about 1560 and was occupied by a family of Grimshaws for about 150 years starting in 1620. Apparently little is known about this family or its origins, presumably in Lancashire. The contents of the Hall, including many antiques and high-quality artworks, were auctioned off by Christie’s in 2000. A very attractive catalogue was published in advance of the auction. The Hall itself was apparently sold in the same timeframe for £2.4m, and it was recently (November 2003) sold again (for £1.8m). An interesting feature of Grimshaw Hall is the scratching of Nancy and Fanny Grimshaw’s names on one of its glass windows dating back to 1718.

Contents

History and Description of Grimshaw Hall

Accounts of the Grimshaw Family from Publications at the Solihull Library

Was Adam Grimshaw, Forebear of the Knowle Grimshaws, in the Eccleshill Line?

Where is Grimshaw Hall Located?

Photos and Description from Estate Company Website

Descriptions from The Times and The Sunday Times

Additional Photos from Christie’s Catalogue

Was There a Connection Between Grimshaw Hall and Archbishop Grimshaw of Birmingham?

Grimshaw Hall Artwork by W.A. Green

Norton Motorcycle Company – Factory Owned by Recent Grimshaw Hall Owner

Grimshaw Hall as Described in Ditchfield’s “The Manor Houses of England”

Webpage Credits

Thanks go to Marjorie Grimshaw and HiIlary Tulloch for spotting the ad for the sale of Grimshaw Hall in The Sunday Times, November 2003 and for providing images of the ad. Thanks are also expressed to the staff at the Solihull Library for conducting research on the Grimshaw family that gave their name to the hall and for providing publications resulting from their research.

History and Description of Grimshaw Hall

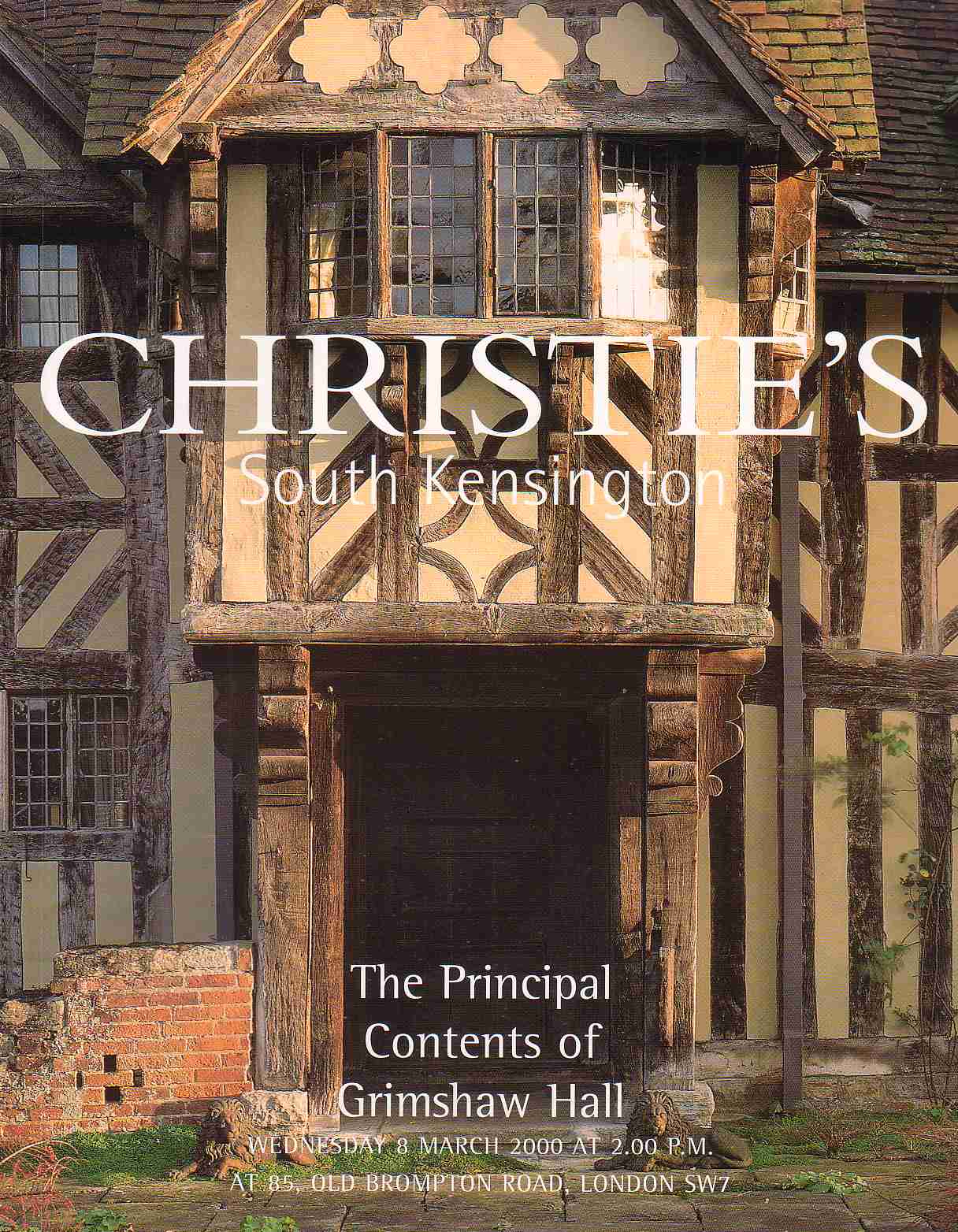

The well-known English auction firm, Christie’s, was commissioned to sell the contents of Grimshaw Hall in 2000. In preparation for the sale, Christie’s published a very attractive catalogue1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Image from Catalogue Prepared for Sale of Contents of Grimshaw Hall

The Christie’s catalogue contains not only photos of the antiques and artwork offered, but also several pictures and a brief description of the Hall. The description, shown below, includes a short history.

GRIMSHAW HALL

There are few half-timbered Tudor houses so finely preserved or so beautiful as Grimshaw Hall, with its many gables, its variety of timber patterns and the fine tone of oak. It is fortunate that until 1886 the exterior was covered with roughcast render, so preserving the oak timbers.

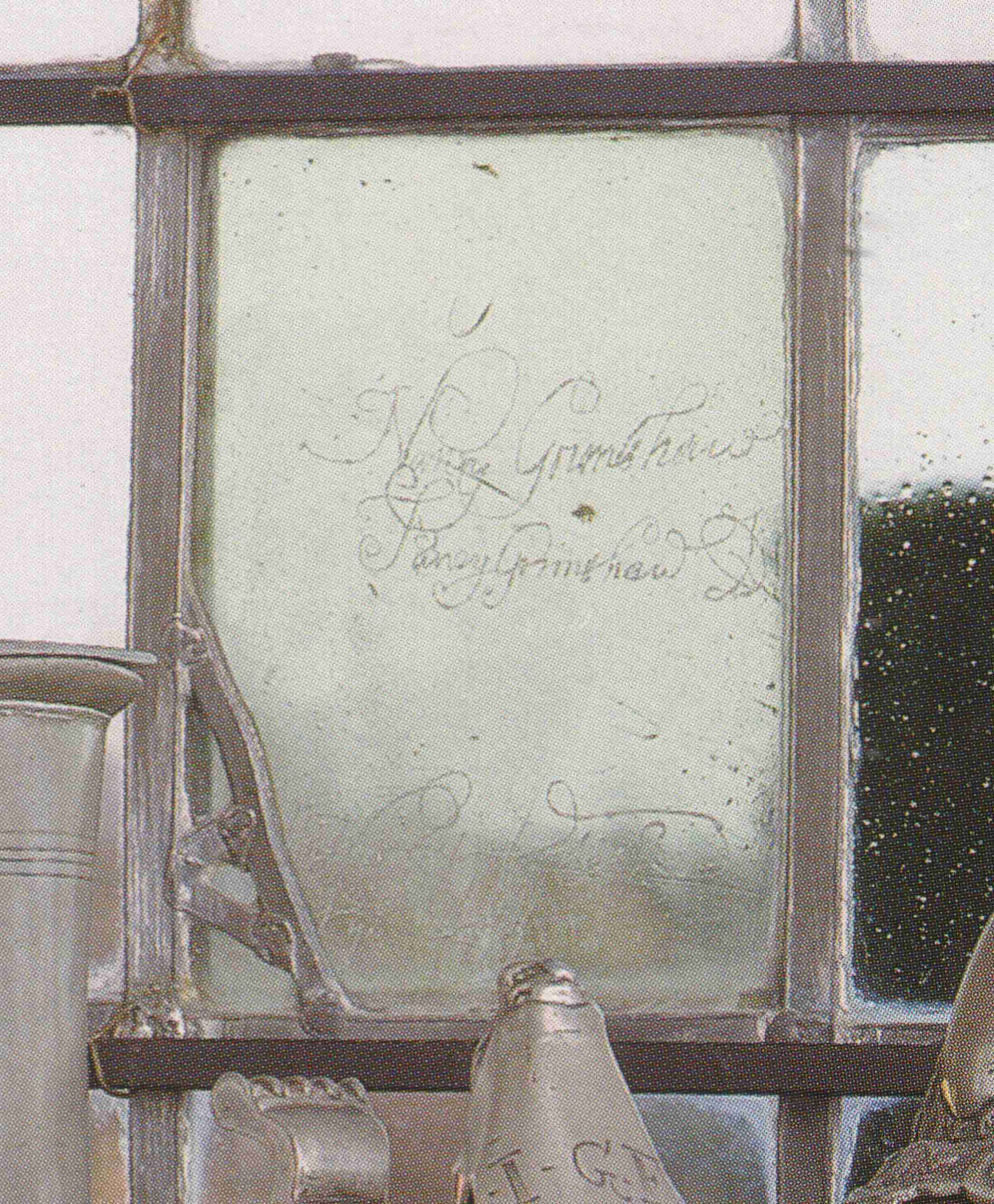

The house. built circa 1560, owes its name to the family, which from 1620 occupied it for one hundred and fifty years. The Grimshaws are an enigmatic family, their names suddenly appearing in local records in 1635 and continuing until 1765, after which they are not mentioned again. However, two girls from the family will be remembered as long as the Hall lasts. Frances and Anne (known as Fanny and Nancy) scratched their names with a diamond on a window in the inner hall (see illustration on page 27). The story behind this is that on Nancy’s sixteenth birthday (September 1718), Richard Grimshaw bought a horse for each of his daughters. Fanny chose the chestnut, leaving Nancy the dapple grey. They then raced four times round a given course, the prize being a diamond ring. Nancy won and inscribed “Nancy Grimshaw, Fanny Grimshaw, My gray has got ye day” on a small green pane in the window.

The exterior plan of Grimshaw Hall is characteristic of a mediaeval house, enlarged and elaborated. The west‑facing front is roughly symmetrical, with a small porch in the centre. The cross‑gabled roof of the porch is a picturesque and unusual feature, which adds greatly to the charm of the front. The functional use of simple timbered “panel and post” construction was developed for the sake of ornamental effect on the the ground floor, with more elaborate patterns appearing on the gables and the porch.

The interior is made up of a succession of charming panelled and halftimbered rooms with low ceilings and open fireplaces. An oak staircase, a massive piece of country craftsmanship, rises through the south wing.

Since moving to Grimshaw Hall in 1960, the present owners have lovingly maintained the house and gardens, while building a collection of furniture, works of art and pictures with a discerning and learned eye. As regular buyers at country house auctions for many years they have furnished their house with warmth and affection.

Amongst the highlights of the items included in the sale is an English early 16th century oak buffet (lot 55). The buffet, which is illustrated as the frontispiece in Percy MacQuoid’s “A History of English Furniture, The Age of Oak” was formerly in the collections of Sir Henry Linger (d.1662) of Freenes Court, Herefordshire and Sir Edward Barry of Ockwells Manor, Berkshire. Rare and interesting early works of art include a carved wood panel of the Duke of Grafton’s Arms, bearing the date 1687 (lot 80) and a Charles 11 bronze bushel (lot 92), cast with the name and date Drayton Vnder Hales, 1670, D.H. and struck with the Royal Arms. Leading the picture section is a large and impressive oil portrait attributed to Robert Peake depicting Cecilia, daughter of Lord Abergavenny (lot 283 ).

The sale includes many pieces of early oak furniture with exceptional patina, an appealing variety of works of art, including two silk needlework pictures (lots 263 and 264) and some fine early English portraits and old master paintings that give the serious collector and the casual buyer alike the opportunity to view such an interesting collection.

One of the more interesting features of Grimshaw Hall is the scratching of Nancy and Fanny Grimshaw’s names on a small window, which is described in the second paragraph of the above excerpt from Christie’s catalogue. One of the photos in the catalogue includes a clear view of the names (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Image of Nancy and Fanny Grimshaw’s names scratched on a window of Grimshaw. As noted above, the complete inscription reads “Nancy Grimshaw, Fanny Grimshaw, My gray has got ye day”. From page 27 of Christie’s catalogue.

Additional detail on the Grimshaw Hall contents sale can be found on Christie’s website at:

Accounts of the Grimshaw Family from Publications at the Solihull Library

The staff at the Solihull Library conducted research on the Grimshaw family associated with Grimshaw Hall and found three excellent publications with accounts of the family. These sources, and the Grimshaw information they contained, are provided below:

The Knowle Society, 1991, The Farms of Knowle – the Text of an Exhibition presented by The Knowle Society1, p. 14:

GRIMSHAW HALL

This elaborately timbered yeoman farmhouse dates from the middle of the 16th century. The Grimshaw family, after whom the house is named, lived there from around 1635 until 1765. The house is reputed to be haunted by the ghost of Fanny Grimshaw, murdered in her bedroom by a jealous lover.

By 1841. the house was owned and farmed by the Willcox family, who also rented Elvers Green Farm and Poplar Farm from the Knowle Hall Estate. The land extended to the canal on the Knowle side of Hampton road and to the River Blythe on the Solihull side. In all there were 134 acres of meadow, pasture and arable. Although the family owned the farm until 1885, it appears to have been let from about 1870 onwards, first to a Mr. William Draper and then (by 1831) to the Mayou family. In early records the house is called Old House Farm: the present name first appears in 1874, but the farm is still referred to by its old name in the 1885 sale brochure.

In 1885 the estate was shared between seven children, none of whom could retain it. One share was used to build Yew Tree Farm in Kixley Lane – owned by the family until 1978. Another share build Grimshaw House on the corner of St. Johns Close and Station Road,k with the cottages next to it. Miss Rosie and Miss Gertie Hinks, who are descended from the Willcoxs, still live there today.

The new owner was Mr. Joseph Gillott, who let the property to various tenants. By this time the house had become covered with creeper, eventually being divided into a number of separate dwellings. About 1913 it was bought and lovingly restored by Mr. J.W. Murray, a Birmingham stockbroker, who had previously lived at Blair Atholl (now demolished and replaced by Stripes Hill House). Queen Mary paid a brief visit in 1937, on the day she also visited Packwood House.

Grimshaw Hall can be seen through the trees from Hampton Road. The present road is a diversion, the original passing much nearer the front of the house.

Wootton, Eva, 1980, The History of Knowle: Kidderminster, Worcestershire, England2 p. 38-42:

Chapter Ten

THE GRIMSHAW FAMILY AND HALL

THE HOUSE WAS BUILT circa 1560, though the family may have lived in Knowle before this time. There is a so-called moat between the present Hall and the River Blyth, known as Grymesawe’s Castle. The spelling is the same as the earliest record of 1319 and this ‘castle’ was probably asighting point on one of the ancient trackways or leys. The large stories are the foundations of a mill belonging to Henwood Nunnery.

In 1319 Adam de Grymesawe married Sibell de Maidenbach, daughter and co‑heiress of Thomas de Maidenbach who inherited the Manors of Aston and Duddeston, thus uniting the Grimshaws and the Holtes of Aston Hall. In 1332 they were living at Aston, The family is thought to have come to Knowle in 1620 to live in Grimshaw Hall. They are an enigmatic family, their names suddenly appearing in records about 1635 and continuing until 1765, after which they are not mentioned again.

Richard Grimshaw, the first in the Knowle Records, had two sons, Richard and Nicholas and three daughters, Clarie, Anne, and Bridget. In 1627 Richard Grimshaw was a signatory to the 39 Report on a Manor Court at Knowle.2

There used to be a tomb slab in Knowle Church ‘to the memory of Mary, fifth daughter of Humphrey Greswolde Esq. of Yardley, wife of Richard

Grimshaw of Bakers Lane, Esq. who died 1669 aged 36 years.Richard husband of Mary, died 1690 aged 58.

They had three daughters, Elizabeth, Mary and Anne. This slab was; recorded in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1793.

One hundred years later another Grinishaw-Greswolde marriage took place, this time between Richard Grimshaw and Martha, daughter of the Rev. Marshall Greswolde of Malvern House; she died in 1755 aged 26 and be in 1765 aged 38.

In 1656 we find Nicholas, presumably the same man who had been fined for assaulting Corbett Printop in 1635, collecting the tax for Maimed Soldiers and Mariners. Later he became a Churchwarden for two years and also gave two years’ service as an Overseer. He may have been the younger son, for there is a Richard at Grimshaw Hall and a Nicholas in Bakers Lane.

Richard married Elizabeth (surname unknown) and between 1695 and 1705 they had six children A Richard was buried in 1690; he is described as Richard Grimshaw, Gentleman … buried the fift day of September and no affidavit was brought of his burying in woollen.

The family which now emerges consists of Richard and Elizabeth, and their six children who were:

Nicholas

born 1695

died 1743

Elizabeth

” 1696

” 1746

Frances

” 1696

” 1746

Anne

” 1696

” 1746

Essex

” 1696

” 1746

These were most closely connected with Grimshaw Hall and we know more about them than any of the others. The young people were high-spirited and headstrong, but their elders did what they could to help the poor and others in the village. Richard gave a cottage and orchard in Golden End for the use of poor and old people; this and four other cottages adjacent are still administered by the Knowle United Charities. Nicholas paid for a seat in the church for the ‘Minister’s family for ever;’ and for straw to thatch the house built for Abigail Welton on the lord’s waste. (See above).

Of the three girls, Frances and Anne (known as Fanny and Nancy) will be remembered as long as the Hall lasts, for they scratched their names with a diamond on the rear window in the Hall. The story behind this is that it was Nancy’s sixteenth birthday (September 1718): their father had two horses for them, and Fanny, being the elder, had the choice and chose the chestnut, leaving Nancy the dapple grey. They then raced four times round a given course, the prize being a diamond ring. Nancy won and on one of the old greenish glass panes about half‑way up on the right in the hall window one can see:

Nancy Grimshaw

Fanny Grimshaw

My gray has got ye day

In 1725, when he was twenty years old, the Overseers paid Mr Essex Grimshaw fourteen shillings for medicines (smallpox was raging at the time). Did Essex do a bit of doctoring? In 1742 Mr Nicholas Grimshaw gent. of Grimshaw Hall was a Feoffee of Solihull School.

There are no Grimshaw marriages in the Knowle Records, only the baptisms of Richard’s six children and the deaths of five. It is said that Nancy ran away and married beneath her, but there is nothing in the records to confirm this.

The Ghost of Grimshaw is said to have been Fanny. She is said to have been too flirtatious at a ball and allowed herself to be driven home. by one of her admirers. Her lover, mad with jealousy, rode after them, pushed his way into the house and tip the stairs after the terrified girl, killing her in her bedroom. He then raced down again to take his revenge upon his rival, but he had jumped into his coach and been driven away and spent the next two years evading his pursuer, who was himself evading justice. The galloping horses and rattling coach wheels were heard from time to time, foretelling the death of someone in the house, or someone belonging to them. The ghost of Fanny in her ball dress was often seen in the house, weeping and wringing her hands.

The Hall.

The Hall is about half a mile East of Knowle on the Hampton Road and is a beautiful example of Elizabethan domestic architecture. It has a main hall‑block between two cross‑wings which project forwards about six feet; in the centre is a fine two-storeyed porch, which completes the E plan often favoured at that time. The porch has a balustered entrance with carved brackets; the front door is old as are the iron drop‑knocker and the ornamental iron plate. The house consists of two storeys and attics and many gables, of which no two are exactly alike in shape or size except those above the porch. The chimneys are in three graceful groups – again all different.

Between the porch and the north cross‑wing is a large gable which combines as a further wing at the back of the building, where it has a projecting stair‑wing with rectangular timber framing with brick infilling. Except for this stair wing most of the lower storey walls are of close‑set studding, Above this there are three diagonal struts giving a fie, ringbone effect, while the really decorative appearance is reserved for the gables, which have quadrant pieces and square framing with brick infilling The sides and back have some close‑studding on the south side, the remainder being square framing with brick infilling. The house faces east and west the latter being the front. To the left of the porch is an old brick mounting block. There was a similar one in High Street outside the White Swan inn which was demolished in 1939.

All the attics and small side windows were plastered over at the time of the Window Tax, remaining covered until 1913 when the property was bought by Mr J.W. Murray who had the house stripped and beautifully restored.

After the last of the Grimshaws the house fell upon hard times, declining from a gracious dwelling to a farm and later being divided into two or more houses. After a time the partitions were removed and it again became one house, but now the timbering which was its chief beauty was plastered over and imitation timbers painted on. The lovely panelling inside was whitewashed or painted and the ceilings papered in attempts to get a lighter effect. Perhaps the removal of some of the large close-growing trees would have been a better remedy. When the plaster was removed, ivy and virginia creeper were allowed to smother the building, a large yew tree grew right against the dining room window and two old walnut trees in the narrow front garden further darkened the house. A narrow path led from the seldom used front door to a small gate in a thick high hedge on to the Hampton Lane, as it was then called.

Before the road widening of the 1930s the Hampton Lane at this point made an S bend, the new road cut through these two loops, leaving Grimshaw Hall, the five villas and cottage in the right bend which became the private drive. Anyone interested in the appearance of the old Hampton Lane (it is one of the oldest of our roads) has only to go along the back entrance to Grimshaw between the canal bridge and the Hall, to see a portion of the deep narrow lone as it was for hundreds of years; it still serves the five Grimshaw villas and Grimshaw Cottage. The small portion of the left part t of the S bend may be seen across the new road from the old lane, the line of trees and a remainder of hedges still show its curve, and over the canal bridge the old lane continues to Waterfield Farm.

In 1913 when Mr J. H. Murray had the Hall restored to its former beauty, all the blocked windows were uncovered, the ivy, etc. cleared away, the yew tree and walnut trees removed from the front garden and all the woodwork carefully cleaned from whitewash and paint. The haunted room was opened up and the whole house made into the beautiful and gracious house we see to‑day. The garden was well laid out and after the 1914-18 war, some of the stables and barns were made into a small house and a large games room. Mr and Mrs Murray were very public spirited and nothing gave them more pleasure than to see the village people enjoying the use of their open‑air swimming pool and the grass and hard tennis courts which they made available to members of the W omen’s Institute and Women’s Club. They also gave the use of the games room to the W. 1. Drama Group, the Rangers and the Wolf Cubs.

In August 1927 H.M. Queen Mary visited Grimshaw Hall enjoying its antique treasures and, lovely garden before partaking of a cup of tea. The cup and saucer which she used were left to the house as a memento of her visit, but unfortunately they were taken away by the next owners when they left Knowle.

The ghosts which gave rise to so much talk and trouble are no longer seen or heard. The fact remains that an unexpected visitor, an acquaintance of the daughter of the house, who stayed overnight, had to be put in the erstwhile ‘haunted room.’ Nothing was said about it and no one had ever told her anything, but during the night she woke up terrified and at last took a blanket and eiderdown and spent the remainder of the night downstairs on the Knole sofa.

Harris, Mary Dormer, 1937, Some Manors, Churches, and Villages of Warwickshire, with an Account of Certain Old Buildings of Coventry3, p. 64-67:

p. 64: photo with caption “GRIMSHAW HALL KNOWLE”

Knowle, Grimshaw Hall

“My Grey has got ye Day.” These words, scratched with a diamond, appear on a pane of glass in a window of the beautiful old house, Grimshaw Hall, which you pass as you leave Knowle by the Hampton Road. The victorious grey, I suppose , was a horse belonging to either Nancy or Fanny Grimshaw, whose names, written with fine eighteenth-century flourishes, may be read above on the same pane. The little bit of doggerel verse seems to make these elated girls, dead long since, real and alive to us. I doubt if a whole volume of biography could do more; a little is so often more telling than much. We cannot rid ourselves of the notion that it is Nancy who is the leader of the affair; that it is her grey whose victory is celebrated on the window-pane. Her name comes before Fannys; though probably she was not the elder of the two; there is also an “N” of a similar flourishing type scratched on the glass of a bedroom window, as if she had chosen to leave her mark in more than one place.

The “grey” was in all likelihood a racehorse of that colour, though it is possible that the exigencies of rhyme may have caused the docking of one syllable of the word “greyhound.” Coursing the hare with hounds was a far older and better-established sport in England than horse-racing; Shakespeare knows everything there is to be known about the former pastime, and spends much pity on the hunted hare, whereas he only once alludes to “riding wagers” where horses are nimbler than the running sands of the hour-glass or clock. It was James I who made horse-racing popular in England, as it had long been in his own country over the Border. Coleshill was, apparently, a center for races in Queen Annes time; at least Addison, in the “Spectator,” in 1711 alludes to a plate offered there as a prize for the fleetest horse. Coleshill is not far from Grimshaw Hall; possibly it was there Miss Nancys “grey” carried of the victory. Well, well, they are dead – these girls, with their light hearts and their laughter, dead, along with the Whigs and the Tories, Marlborough, Mr. Addison of the “Spectator,” and the great Queen Anne herself. Thinking of them, “I feel chilly and grown old,” as Browning says, speaking of the dear dead women of old Venice, who had such golden hair.

A GHOST-STORY. There is a ghost-story connected with Grimshaw Hall – there would be! A beautiful lady, dressed for a ball, “walks” in one of the bedrooms. They say she was murdered by a jealous lover, who afterwards fought with his rival in the stable-yard, which has likewise a reputation for uncanny visitants. This story must not concern either the Fanny or the Nancy of the window-pane. Their memories should be free from all associations of horror like to this. But all we really know of them is that their names occur among the very few records of Grimshaw baptisms in the Knowle church-register. Frances, daughter of Mr. Richard Grimshaw, gentleman, was baptized on March 22, 1701, and Anne, daughter of Richard Grimshaw on December 15, 1702. There is one more entry, which may allude to the Nancy of the grey horse. It is not a marriage; no Grimshaw marriages are recorded in the registers. Anne Grimshaw was buried on September 12, 1737. Her age is not stated, but, if born in 1702, she would be thirty-five years old. The life of spinsters in those days was cramped and often wretched, and to go off “in a decline” was by no means an unusual fate for many of that despised class.

Save for the tops of the gables, Grimshaw Hall remained until 1886 smothered in rough cast. The exterior was then uncovered by a late owner, Mr. Gillott; but it remained for its present possessor, Mr. J.W. Murray, to free the interior form disfigurements, and to show the beauty of the place all complete. The Hall, to which the vanished family of Grimshaw have given their name, must be the most elaborate timber dwelling in the Elizabethan style in Warwickshire. There is almost a Lancashire or Cheshire touch about the circular braces in the timbers of the top storey; for it is in the north-western shires that we get the most highly-decorated buiding in wood. The name, too, sounds like a corruption of the place-name Grimshargh, near Preston, Lancashire, so the family may have originally come from that quarter and designed the house in the local style of an older home.

There were Grimshaws in Warwickshire, however, in the fourteenth century at Aston and Dudston, in what is now Birmingham; they were connected with the Holts of Aston, and their arms are found quartered in the Holt heraldry on Aston Hall, only material to establish the connection between the Aston and Knowle branches is lacking. What is possibly a distorted version of the name appears among those of the brethren of the Knowle Guild in the Register in 1498. It is there written “Grimshey.” But, again, further information is to seek.

THE GRIMSHAW FAMILY. In the second year of Charles Is reign (1626-7), the family appears as settled at Knowle. Richard Grimshaw is then mentioned as one of the defendants in a lawsuit touching payments of worksilver by copyholders of the manor. Worksilver, a relic of serfdom, was a commutation of obsolete personal service – reaping, mowing, and so on – due from the tenant to the lord, for a money payment. Grimshaw was probably a tenant of the manor holding by copy of court-roll. There were strange incidents still adhering to copyhold tenure even as late as the seventeenth century. The land at Knowle descended not to the eldest, but to the youngest son, or, if male heirs failed, to the youngest daughter by the first wife of the father. Nevertheless, there was little to distinguish copyhold tenure from absolute ownership, as far as security and power of sale went in those later days According to the Poll-tax of 1660, two members of the family are described as yeomen, and the holding of the more wealthy one was worth the sum – a considerable one, according to the ten value of money of £120 a year. The name of Grimshaw appears here and there in the parish registers, which date from 1682; the last entry concerning them being the note of the burial of Richard Grimshaw in 1765. Thus the family disappeared, as the yeomanry have gradually disappeared from England, owing to a multitude of causes, and in many cases their little holdings have been merged into great estates.

FEATURES OF NOTE. The house, which faces east, has a projecting porch and two projecting wings. The porch-gables face three ways, and by the side of the porch is a picturesque mounting block. The beautiful patterns of the timbers of the three storeys vary in design; some are straight, some placed diagonally, some form curves and circles, giving to the whole an effect of wonderful richness. The brick-filled eastern side facing the terraced garden and a stretch of water, though plainer, is charming; here, too, an old dove-cote comes in sight. The fluted brick chimneys give an admirable touch.

Inside the house in the hall and dining-room, you find all the pleasant features of a time when house-building was a great art. Panelling has been freed from coats of point; deal-casings have been pulled down; and that monstrous modern invention, the kitchener, has given way to the hearth and ingle-nook of old time. Little cupboards – such as I saw at Henfield nearby appear above the beam which spans the hearthplace. The Grimshaws used to sharpen their weapons on the stone by the side of the fire; the marks are still there.

In the hall is the pane of glass engraved with the girls names. Plaster and paint have also disappeared from the drawing-room, where I was shown an Elizabethan shilling, dated 1561, dug up during renovations, and fragments of old bottles, found in a rubbish-heap, bearing the name “R. Grimshaw.” In this room is a mirror framed in beadwork of the time of William and Mary. The staircase is original, and the huge balls which terminate the newel-posts can be taken off. They would make by no means negligible weapons against intruders who were unwelcome. Upstairs are a curious little room in the shape of the letter “L,” the haunted chamber, and a charming morning-room open to the roof. Everywhere, indispensable modern “improvements” have been contrived with little disturbance as possible to the ancient features of the house. One relic, luckily preserved in a passage, is a piece of old plaster stenciled with a wavy floral pattern. I daresay a plaster coating, decorated thus, was by no means an uncommon feature of a timber-build house. It would help to keep it worm.

Queen Mary visited Grimshaw Hall in 1927.

[I am greatly indebted to Mr. and Mrs Murray for permission to visit Grimshaw Hall, and also to Mrs. Murray for much information. I have relied on the late Canon Downings “Records of Knowle,” and an article on Grimshaw Hall by Mr. A. Oswald in “Country Life,” Sepember 16, 1933. Mr. H.M. Jenkins furnished me with the Addison reference to the Coleshill races.]

Was Adam Grimshaw, Forebear of the Knowle Grimshaws, in the Eccleshill Line?

The following excerpt is from the book by Eva Wooten described in the preceding section:

In 1319 Adam de Grymesawe married Sibell de Maidenbach, daughter and co‑heiress of Thomas de Maidenbach who inherited the Manors of Aston and Duddeston, thus uniting the Grimshaws and the Holtes of Aston Hall. In 1332 they were living at Aston, The family is thought to have come to Knowle in 1620 to live in Grimshaw Hall. They are an enigmatic family, their names suddenly appearing in records about 1635 and continuing until 1765, after which they are not mentioned again.

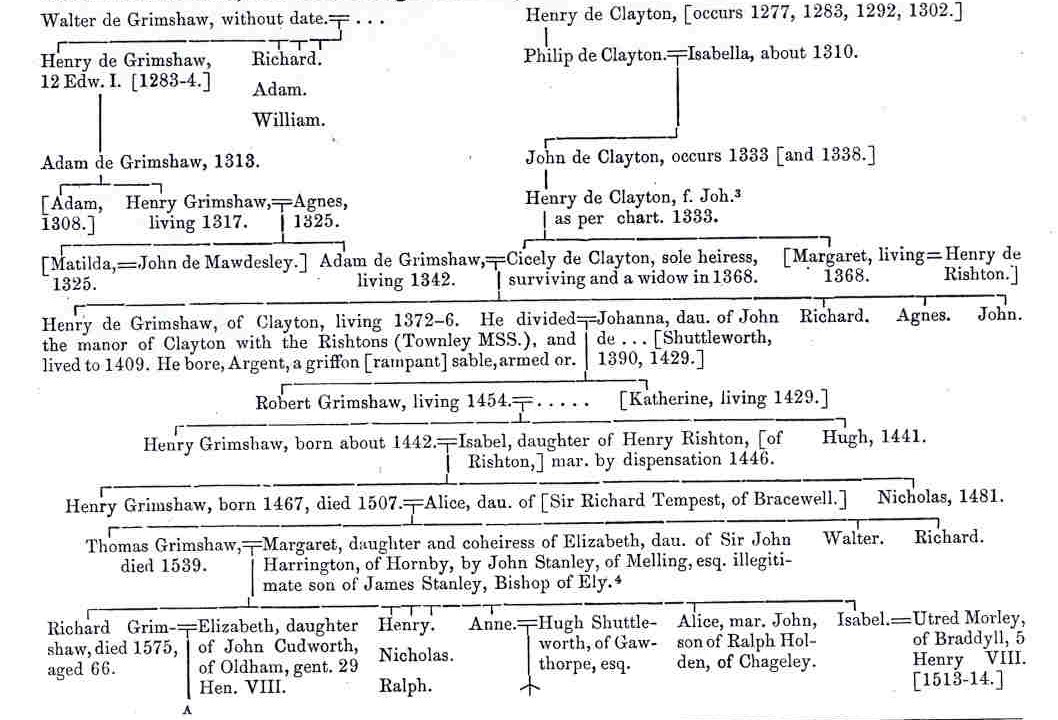

The Adam Grimshaw who married Sibell de Maidenbach may have been the great-grandson of Walter Grimshaw, shown in Whitaker’s descendant chart of the Eccleshill line of Grimshaws below. This Adam is indicated as [Adam, 1308.]

Where is Grimshaw Hall Located?

Grimshaw Hall is located at Knowle, which is near the M42 about eight miles southeast of the city center of Birmingham (Figure 3). It is also located about 15 miles north of Stratford-upon-Avon, home of William Shakespeare.

Figure 3. Location of Grimshaw Hall at Knowle (source: www.multimap.com)

a. Grimshaw Hall is located on the north edge of Knowle:

b. Knowle is located about two or three miles east of the intersection of the A34 with the M42:

c. Knowle is about 8 miles southeast of central Birmingham:

Stratford-upon-Avon, home of William Shakespeare, can be seen at the southern edge of the above map.

Photos and Description from Estate Company Website

Grimshaw Hall was apparently sold at or shortly after the time of the Christie’s sale of its contents in 2000. The Hall was sold again in November 2003, with Andrew Grant as the estate agent. This firm’s website provides six good photos of the Hall as part of their promotional program (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Photos of Grimshaw Hall (exterior and interior views) and the surrounding grounds. From Andrew Grant website (http://www.andrew-grant.co.uk).

The Andrew Grant website also includes the following particulars about the property:

Knowle, Solihul, West Midlands

£1,750,000FOR SALE BY PUBLIC AUCTION On Wednesday 26th November 2003 At The Forest, Dorridge, Solihull At 2.30 pm

Dorridge 2, Solihull 3, Kenilworth/Birmingham 8, Coventry 13, Warwick 15, Stratford-upon-Avon 19, Worcester 31, London 106, M42 – 1 mile (approx)

A FINE EARLY 17TH CENTURY GRADE I ELIZABETHAN MANOR HOUSE TOGETHER WITH EXTENSIVE OFFICE LEISURE COMPLEX, OUTBUILDINGS, GARDENS AND GROUNDS

Grimshaw Hall: Banqueting hall. 3 Reception rooms. Library. Kitchen/breakfast room. 2 Cloakrooms plus sitting room. 7 bedrooms (1 e/s). 2 Bathrooms. 3 Attic rooms. Cellar. Approx: 6,000 sq ft. Courtyard Complex: Approx: 6500 sq ft. The Coppice: 3 Reception rooms. 5 Bedrooms. Garden. Approx: 3700 sq ft. Staff Bungalow: Approx: 980 sq ft. Detached Traditional Outbuildings: Approx 530 sq ft. Garden. Parkland. Lake. Around 17 acres

7 Bedrooms

23’9×12’1

17’8×14’9

16’7×14’3

15’3×16’1

19’9×10’11

10’1×6’26 Receptions

23’7×12’8

19’10×16’11

16’x14’1

17’2×15’7Kitchen

17’9×14’6

The Andrew Grant website provides the following self description:

Andrew Grant Chartered Surveyors, Auctioneers & Estate Agents

Despite the inauspicious launch date (April 1st 1971) Andrew Grant has from day one gone from strength to strength – innovating, challenging established practice, embracing the latest technology and providing an unrivalled personal service from eight residential offices, a London office in Pall mall and specialist departments in Surveys, Fine Art, Commercial, Lettings and New Homes, all staffed by experienced and well trained experts in their own particular fields.

A progressive and progressing company, Andrew Grant is recognised as the leading Independent Estate Agency in the Midlands and the company’s distinctive red and white For Sale boards are a familiar sight.

Andrew Grant provides clients with a service which meets their needs and surpasses their expectations combining principles of professionalism and integrity.

According to the Andrew Grant website, Grimshaw Hall sold on November 26, 2003 for £1.8m.

Descriptions from The Times and The Sunday Times

On November 16, 2003, The Sunday Times ran a piece on Grimshaw Hall in its Home section (Section 10, p. 6) that included a good photo and the following description (thanks to Marjorie Grimshaw for finding this article and to Hilary Tulloch for providing the exact reference):

Warwickshire £1.75m

Motorbike fan and Midlands businessman Keith Moore bought Grimshaw Hall two years ago for £2.4m. Now, it’s going under the hammer at auction with a guide price of £1.75m. Moore’s bike collection and the contents of the Norton motorcycle factory at Shenstone, near Lichfield, which he owned and which closed after his death this year, are being auctioned separately in an event billed as the end of a chapter in British motoring history. The Grade I-listed Elizabethan manor house has seven bedrooms, a banqueting hall and a morning room. There’s a courtyard complex with indoor pool, kitchen and offices, a five bedroom converted coach house and a two-bed staff bungalow, all set in 17 acres with a lake. It is on the edge of the village of Knowle, three miles from Solihull and eight from Birmingham. Andrew Grant Country Homes, 01905 24477, www.andrew-grant.co.uk.

Then on November 21 The Times (“TimesOnLIne”) published the

description of Grimshaw Hall (http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,587-900718,00.html) shown below:

November 21, 2003

Good Manors

Beam Back to the Tudor Era

by Marcus Binney of The Times

Grimshaw Hall Uses Its Exposed Elizabethan Timbers to Great Effect

GRIMSHAW HALL takes you back 400 years in an instant. It looks, so it seems, exactly as it did in 1600, with leaded windows, soaring chimneys and overhanging upper storeys. Here is the full dazzling virtuosity of English half-timbering with herringbone and lozenge patterns almost as intricate as the markings of a leopard.

The front is a perfect example of the E-plan in honour of Elizabeth I, with projecting ends and central porch. Better still, the sides and the back are every inch as picturesque. Then the thought dawns: how can the house have survived so miraculously intact through the centuries without a Georgian sash or Victorian servants wing?

The answer is that, yes, the clock has been put back on two occasions, but so cleverly and sensitively that it is hard to tell the old work from the new. This is not pastiche but Victorian Arts and Crafts and the Edwardian love affair with the past. On both occasions exceptional architects were involved. They adopted an approach that English Heritage and too many local authorities might summarily reject today —- that of blending the old with the new to create a seamless whole. The house was built in Knowle, near Solihull, by the Grimshaws in the second half of the 16th century. By the 19th century it had become three cottages. It was then acquired by Joseph Gillot, a pen manufacturer known as “His Nibs”. He brought in the architect J. A. Chatwin, who had the delicate task of restoring and extending what is now Birmingham cathedral. Just before the First World War the family called in W. Alexander Harvey, who laid out the famous Bourneville Estate for the Cadburys. The result is a composition richer and grander than most half-timbered houses in Sussex or Suffolk and as exuberant as any in Cheshire.

The bigger surprise is to find that it is going up for auction on November 26, barely a month after it was first advertised, with a guide price of £1.75 million. Prospective buyers are coming forward in such numbers that a whole series of viewing days have been organised and an auction may indeed be the way of prompting the fiercest and fastest bidding.

For this is a house that almost certainly will go to someone living in the Midlands or with very close business or family connections there. For those who live or work in the vast bustling megalopolis that is Birmingham, this is a prime site indeed.

Although it is only three miles from Solihull, Knowle retains the feel of a country village, with a few too many modern buildings on the high street perhaps, but a ravishing medieval church at the end. Grimshaw Hall is secluded in the centre of its 17 acres of grounds – with extensive lawns flanking the drive, trim yew hedges enclosing a modest formal garden to the side, and further lawns sloping down to a small lake. There are white doves on the roof of the dovecote, ducks on the water and Canada geese.

Part of the substantial coach-house block has been converted into an indoor swimming pool with a dance floor next door. The wall of sliding glass may not be to everyones taste when seen from the outside, but it is not visible from the house itself.

Inside, Grimshaw Hall lacks the great chamber with rich plasterwork that one hopes to find in a house of this date but the exposed timbers give every room great character: timber posts in the walls, timber beams and, at the top of the house, the roof trusses exposed to dramatic effect. At present there are just two discreetly placed bathrooms for seven bedrooms — and more will not be easy to achieve even by converting bedrooms.

The house is in good condition, but gives the impression that its last owner, Keith Moore, a businessman and motorcycle enthusiast, barely occupied it. Solihull Council last year fired a warning shot that may deter developers from seeking to break up the Grade I listed property, when officers recommended the refusal of an application to turn the outbuildings into ten dwellings and build 12 garages. The application was subsequently withdrawn.

This is one of the best surviving country houses in the Birmingham area, not too large for family use, and should remain in one ownership.

Additional Photos from Christie’s Catalogue

From the many excellent pictures in the Christie’s catalogue4, a few have been selected for presentation in Figures 5 to 7 below.

Figure 5. Cover of Christie’s Catalogue for the Sale of the Contents of Grimshaw Hall

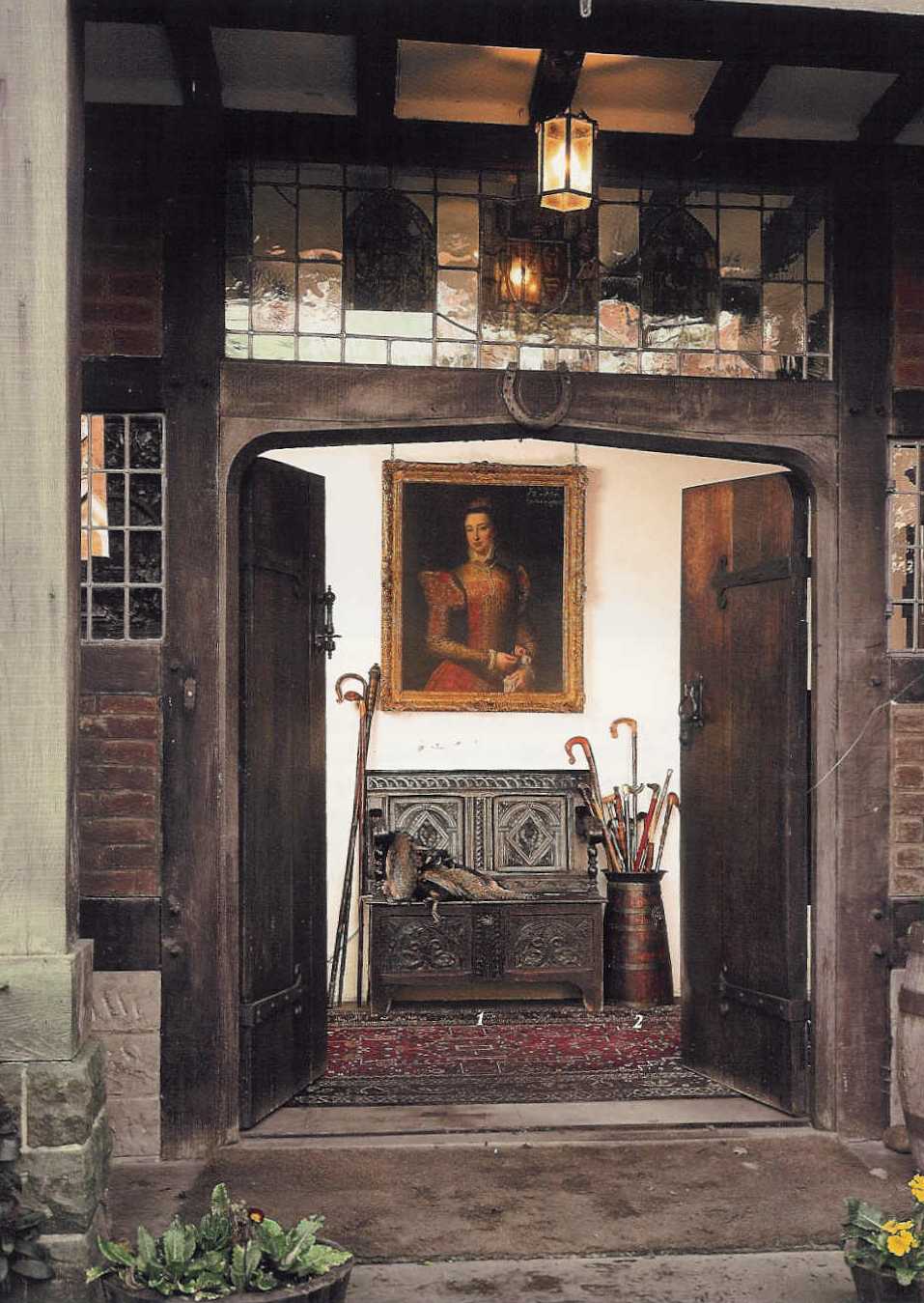

Figure 6. Front view of Grimshaw Hall

Figure 7. View through one of the doors of the Hall

Was There a Connection Between Grimshaw Hall and Archbishop Grimshaw of Birmingham?

Francis Joseph Grimshaw who was appointed as Archbishop of Birmingham in 1954 after being ordained in 1926 and consecrated as Bishop of Plymouth in 1947. Archbishop Grimshaw died on March 22, 1965. Francis Grimshaw was from Bridgwater, Somerset, where he grew up in a family that had strong connections to St. Josephs Catholic Church.

There was apparently no connection between the Archbishop and Grimshaw Hall because the Hall was named in the 1600s, long before the Archbishop arrived in Birmingham.

Archbishop Grimshaw School, which was named after Archbishop Francis Grimshaw, is located in the southeast outskirts of Birmingham (in Solihull), only about three miles northwest of Grimshaw Hall. It is described on a companion webpage on this website. According to the school website (address shown below), “Archbishop Grimshaw is a Roman Catholic School in Chelmsley Wood, Solihull, Midlands. There are approximately 1300 students from 11 to 19 and over 70 staff. Courses on offer range from GCSE and A levels to GNVQ.”

The close proximity of Grimshaw Hall and Archbishop Grimshaw School appears to be coincidental.

Grimshaw Hall Artwork by W.A. Green

W.A. Green made three drawings of Grimshaw Hall in 1928, 1940, and 1949 which are provided on the following website:

These drawings are shown below, followed by information on Mr. Green as an artist.

GRIMSHAW HALL, KNOWLE, Warwickshire

Grimshaw Hall, Knowle, Warwickshire (painted 1928).

GRIMSHAW HALL, KNOWLE, Warwickshire

Knowle, Grimshaw Hall, built 1601. A fine example of an early 17 cent. timber house (drawn 1940)

KNOWLE, Warwickshire

Grimshaw Hall. A lovely 17th century timbered hall, ranking amomg our finest old houses (drawn 1949).

HISTORIC BUILDINGS IN PEN & INK (a few pencil & watercolour)

THE WORK OF WILLIAM ALBERT GREEN 1907 – 1983

INTRODUCTION

William Albert Green (Will A. Green) was born in Birmingham, England in 1907. With his wife Edith and two children (Edwin and Marian) they moved to Ludlow in Shropshire in 1952. He died in 1983.

He began drawing in his teenage years, using pencil and water color, but then turned to pen and ink working. He continued until a few years before his death although he suffered throughout his life with defective eyesight.

He concentrated on the historic buildings in the English Midland counties of Warwickshire, Worcestershire, Staffordshire, Herefordshire, Leicestershire and Shropshire. Usually travelling by pedal cycle to these locations. However the collection does include historic buildings of Pembrokeshire, Devon, London etc.

Initially the drawings were for his own private collection. But later sold them at a nominal price to family and friends, then the major Midland omnibus company used some of the pictures to illustrate their tour guides. His pictures appeared for many years in The Birmingham Weekly Post illustrating a weekly rambling article by John Hingley. Also in other Midland newspapers including The Sunday Mercury, The Birmingham Post, and The Birmingham Mail The pictures also appeared in English Counties guide books published by the Littlebury Press, and a series CATHEDRALS OF BRITAIN appeared on the back of England Glory matchboxes.

Many of the buildings have been demolished, and so this collection forms a valuable historic record which we wish to share with others.

If you have any information or stories about these buildings we would be pleased to hear from you. Also we would be delighted to hear from anyone who has any of W.A. Green’s drawings which do not appear on this website.

Norton Motorcycle Company – Factory Owned by Recent Grimshaw Hall Owner

As noted in the above descriptions of Grimshaw Hall, Keith Moore was the last owner before its recent sale on November 26, 2003. Keith owned the Norton motorcycle factory at Shenstone. A brief description of Norton motorcycles was found on the internet at the following website:

The Norton Story – a Ride to Remember

IGNITION: 1898-1938

Norton’s history begins in 1898 in England with the birth of the Norton Manufacturing Company, which supplies components for a youthful invention called the motorcycle. Founder James Lansdowne Norton builds his first motorcycle in 1902 and by 1907 the course is defined as H. Rem Fowler drives a twin-cylinder Norton to victory at the Isle of Man TT.Speed is the priority over the next two decades as Norton develops and improves motor after motor, culminating in Arthur Carroll’s new OHC engine in 1929. That engine drives the company’s racing dominance in the 1930s, establishing Norton’s legacy for unapproachable performance.

FULL THROTTLE: 1939-62

With the onset of World War II, Norton is pressed into service as production replaces racing as the focus. The company builds 100,000 models of the 1937 16H for the military over a six-year period, and the abundance of parts and components are a large factor in subsequent restorations that keep vintage Nortons on the road today.After the war, Norton resumes its racing success while producing successful new models for the public. The Manx is launched in 1946, followed by the Dominator twin engine. Norton is acquired by AMC in 1953, single-engine production eventually dwindles, and the company suffers under the financial needs of the parent company.

CHANGING GEARS: 1963-77

The last of the Norton singles are produced in 1963 and Dennis Poore buys the company in 1966. The old Dominator engine is replaced by the Atlas, which powers the new Commando beginning in 1969. Over the next five years, several models of Commando emerge, gaining long-lasting popularity for their looks and style.A government-brokered partnership with Triumph/BSA brings with it financial difficulties for Norton, ending day-to-day production for the public.

IDLING: 1978-1999

From 1978-87, Norton Motors exists solely as an R&D company, eventually developing an air-cooled twin rotor engine and once again developing models for road racing on a national level. Numerous attempts to make Norton a commercial success fail.

Grimshaw Hall as Described in Ditchfield’s “The Manor Houses of England”

A book by Ditchfield5 on the manor houses of England includes a sketch of Grimshaw Hall as the Frontispiece of the book as well as a brief description of the Hall in the section on materials of construction. The excellent Frontispiece sketch is shown below.

The title page of Ditchfield’s book, and an image of the reference to Grimshaw Hall on page 75, are shown below.

In Chapter IV, “Materials of Construction”, Section on “Timber”, Page 75:

The preface and first chapter of “The Manor Houses of England” are provided below to set the context for including Grimshaw Hall in the book.

PREFACE

THE object of this book is to describe and illustrate the old country manor-houses of England, which are fast falling into decay, and are being replaced by modern and less picturesque buildings. Many of them stand in remote, inaccessible and little-known parts of the country ; and their remarkable beauty, their historical associations and architectural merits, may ‘have escaped the attention of many who love to explore the English countryside. ‘It has therefore been deemed advisable to depict and to describe a series of typical examples taken from different counties and constructed of various materials, so that a record may be made, ere many may entirely disappear. The manor-house is the principal dwelling-place in most. villages, and to it the chief attention has been paid; but as this book is a study of the domestic architecture of the style of dwelling that ranked between the mansion and the farm or cottage, it has been thought well to illustrate the work by including some examples of a kindred nature that cannot be strictly included in the generic term manor-house.

It would have been an easy task to fill the volume with pictures and descriptions of well-known buildings that have often been photographed and sketched, and about which much has been written, but an attempt has been made to go outside the beaten track, the oft-trodden road, and to record the more unusual examples not so well known. The description of the details of the manor-houses of England has been given in plain language, as free as possible from technical terms ; and the subject has been treated for the purpose of interesting the general public rather than for the edification of the architectural expert.

The author desires to express his grateful thanks to Messrs. Batsford for much assistance they have rendered to him in the preparation of this book, and for their valuable advice and personal interest in the work ; also to the artist, Mr. Sydney Jones, for his descriptive notes on some of the houses which the writer had not an opportunity of personally visiting, and to Mrs. Arthur Stratton for kindly searching for some references in the British Museum with regard to the history of some of the manors.

P. H. DITCHFIELD.

BARKHAM RECTORY, BERKSHIRE,

January, 1910.

Chapter 1 is shown below.

THE MANOR-HOUSES OF ENGLAND

I

INTRODUCTORY: THE MANOR-HOUSE

ENGLAND is remarkable for the number and beauty of the old country houses, set amid pleasant scenes, that abound in various parts of our island. Hidden away from the gaze of the multitude in sequestered villages and obscure hamlets, they are very humble-minded, very retiring. They do not court attention; these English manor-houses, or seek to attract the eye by glaring incongruities. or obtrusive detail. They seem in quest of peace, and love obscurity. Hence few know how fair they are, how full of grace and charm, as they stand in their sweet old-fashioned gardens surrounded by rare blendings of art and nature in park and pleasance. They brood in their old age over many scenes of bygone history, over the memories of sire and grandsire and retain vivid recollections of the vigorous old squire and his lady who reared these ` walls in Tudor days and carefully saw to the carving of his and his dame’s initials over the doorway – R. D. and E. D. 1595 A.D.

The builders of these houses were animated by that same spirit which moved Sir William Temple, cultured diplomatist, philosopher and garden lover, to write; “The greatest advantages men have by riches are, to give, to build, to plant and make pleasant scenes.” And certainly they showed by their buildings that they were men of taste and refinement, very different from Macaulay’s unflattering picture of the old English country squire who is represented as an ignorant boor. It is not in the greatest mansions, the vast piles erected by the great nobles of the court, enriched by the plunder of the monasteries, that we find such artistic perfections, but most often in the smaller manor houses of the knights and squires. These are the buildings which delight us, the charms of which we are attempting to set forth in this book. The great noblemen and courtiers were filled with the desire for extravagant display, and erected such clumsy piles as Wollaton and Burghley House, importing Flemish and German artisans to load them with bastard Italian Renaissance detail. Nothing could be worse than some of these vast structures, with their distorted gables, their chaotic proportions and their crazy interpretation of classic orders. Contrast these vast piles with the typical Tudor manor-house, the means of the builders of which, or their . good taste, would not permit of such a profusion of these architectural luxuries, and you will discover the far, greater attractiveness of the humbler dwelling. It is unequalled in its combination of stateliness with homeliness, in its expression of the manner of life of the men who built it.

Such a noble Tudor house is Whittington Court in Gloucestershire, in the delightful region of the Cotswolds. It is at once stately arid homely, and its picturesqueness is in no way diminished by the Queen Anne addition with its conspicuous bay. Its three graceful gables, tall chimneys, and mullioned windows are worthy of the art of their Tudor builders. ‘

These men built not only for themselves but for their sons and grandsons. They lighted what Ruskin calls the Sixth Lamp of Architecture, the Lamp of Memory, and considered it an evil sign of a people for houses to be built to last for one generation only. They felt that

” having spent their lives happily and honourably, they would be grieved, at the close of them, to think that the plan of their earthly abode, which had seen, and seemed almost to sympathise in all their honour, their gladness or their suffering – that this, with all the record it bare of them, and all of material things that they had loved and ruled over, and set the stamp of themselves upon – was to be . swept away, as soon as there was room made for them in the grave ; that no respect was to be shown to it, no affection felt for it, no good to be drawn from it by their children ; that though there was a monument in the church, there was no warm monument in the hearth and house to them ; that all that they had ever treasured was despised, and the places that. had sheltered and comforted them were dragged down to the dust. I :say that a good man would fear this ; and that, far more, a good son, a noble descendant, would fear doing this to his father’s house…. When men do not love their hearths, nor reverence their thresholds, it is a sign that they have dishonoured both…. Our God is a household God as well, as a heavenly one ; He has an altar in every man’s dwelling; let men look to it when they rend it lightly and pour out its ashes.”a

Such feelings seem to have animated the builders of the gems of domestic architecture that adorn our country-side. . They stamped their impress on the homes they reared. They. expected their children to respect their gift to their families. They carved their names or their initials or their arms over their doorways. They adorned them with texts or homely verse, pious thoughts, or quaint or humorous conceits. They built surely and well so that their houses might last, not for their own pleasure nor for their own use, but for their descendants, who would thus venerate the hand that laid those stones and respect the memory of their fore-fathers and the honour of their house.

We shall visit many such houses during our peregrinations. As an example of the long, low type of restful English manor-house we could not find a better instance than the curious half-timbered mansion known as Bott’s Green House, near Shustoke, in Warwickshire. Its curved and slanting braces and its fine porch and entrance gate are charming features. It stands completely away from the busy haunts of men in the midst of an unspoilt country. The fleur-de-lis of the Digby family is very prominently inserted in the front. Within there is a carved stone mantelpiece carefully painted and grained to imitate wood, and upstairs a small panelled room of plain design.

In contrast with this peaceful abode is the Yorkshire manor-house of Lawkland Hall upon the borders of: Lancashire, situated on the wild moorland that separates the two counties. It belongs to a different type, and has a stern rugged look which harmonizes well with its surroundings.

Time has wrought its ravages on many of these old houses. Families have lived and died out. Few, save the delver in old records, can tell the names for which those initials R. D. and E. D, stand. The golden stain of time gives light and colour to its architecture; but often ruin and decay have also left their marks. Reckless owners who love new things, new fashions and new styles, have doomed many of them to death. At the beginning of the last century there was a veritable rage for pulling down old mansions. You can still see the terraces of the garden, the old fishponds and possibly the moat, but the house has gone, a prey to the vandalism of the age. Others have succumbed to new inventions. Coal fires were unusual when the chimneys were built with a fatal beam running across their cavities. Hence fires have destroyed many of those ancient mansions which often stand in solitary state far from the nearest fire-engine station, and nothing is saved: Only a tithe is left of these pleasant houses. It is well, therefore, to survey them before they vanish, to gather up the fragments that remain, to learn from them how to build surely and well, to avoid the construction of those : ” thin, tottering, foundationless shells of splintered wood and imitation stone,” and to take as our models these beautiful dwellings that our sires have left us.

aRuskin’s Seven Lamps of Architecture6.

References

1The Knowle Society, 1991, The Farms of Knowle – the Text of an Exhibition presented by The Knowle Society: Privately Published, p. 14:

2Wootton, Eva, 1980, The History of Knowle: Kidderminster, Worcestershire, England; Kenneth Tomkinson Limited, p. 38-42:

3Harris, Mary Dormer, 1937, Some Manors, Churches, and Villages of Warwickshire, with an Account of Certain Old Buildings of Coventry: Coventry, England, The Coventry City Guild, Memorial Volume, unk p. (Originally published in “The Coventry Herald” over a period of five and a half years, from July. 1930, until their authors untimely death in a road accident in March, 1936), p. 64-67:

4Christie’s South Kensington, 2000, The Principal Contents of Grimshaw Hall: London, Christie’s South Kensington, Privately Published Catalogue, 104+ p.

5Ditchfield, Peter H, 1910, The Manor Houses of England: London?, Batsford, 211 p.

6Ruskin, John, 1907, The Seven Lamps of Architecture: Leipzig, Bernhard Tauchnitz, 334 p.

Webpage History

Skeletal webpage posted November 2002. Upgraded with input from Marjorie Grimshaw and Hilary Tulloch, December 2003. Upgraded February 2004 with addition of articles from three references. Updated November 2007 with section on origins of Adam Grimshaw and with addition of material from Peter H Ditchfield’s “The Manor Houses of England”.